If you’re a UX designer, you’ve probably designed a lot of forms and web (or app) pages in which the user needs to choose between options. And as a designer, you’re likely familiar with best practices for designing forms. Certainly, much has been written and discussed about this topic. So, you probably know all about how best to label and position form fields and so on for optimal usability.

But have you thought about how the design of a form affects the user’s decision-making? Have you ever considered to what extent the design itself affects the choices people make? As always in design, there are a variety of ways to design a form or web page.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- How To Build Honest UIs And Help Users Make Better Decisions

- P Vs. NP: The Assumption That Runs The Internet

- What You Need To Know About Anticipatory Design

- Designing A Dementia-Friendly Website

For example, let’s say you’re designing a system in which the user needs to indicate whether they would like to sign up for a particular preventive medical procedure, like a flu shot. You could design the form in a number of ways. For example, you could provide a checkbox where the user either opts in or out. Alternatively, you could design it so that the user is required to explicitly choose between two options (via radio buttons).

Examples of these two approaches are shown below:

Would it matter which way you design it? Would the user make the same choice regardless of which design they encounter? Or could the user potentially be led to make a different choice merely as a result of how the choice is presented or designed?

The Power Of Defaults

One key difference between these two designs is that the checkbox requires a default state. That is, upon display, the checkbox will appear either checked or unchecked, as opposed to the radio buttons, which do not require a default selection. In the second example, even if the user does nothing, a “choice” has already been made, via the default.

A robust body of research has shown that when a default choice is offered, most people do not deviate from it. For example, if the box is checked by default, many don’t uncheck it (and vice versa). Making an explicit decision requires effort, after all. Time, thought and consideration are often required to determine the best choice. It turns out that people are remarkably sensitive (and averse) to the amount of effort that making a choice demands.

People are also remarkably sensitive to any possibility of incurring a “loss” that might then subsequently trigger feelings of regret. Especially when one is unsure how to choose, not making a choice (by simply accepting the default) feels better than actively making a choice that might end up being the “wrong” choice. Because people often have an unrealistic expectation that they will have more time in the future to make a more informed decision, procrastination also works in favor of acceptance of the default. Deviating from the default requires an explicit action, which people delay in taking. In many ways, defaults make decisions feel easier and less risky.

Designing For An Explicit Choice

The judicious use of defaults, then, has proven to be a key driver in the choices that people ultimately end up with, in large part because many people simply go with the default option. But one problem with passive decision-making is that it’s less likely to engender the kind of committed follow-up that is often essential to implementation of the decision, such as in the earlier example of the flu shot. Wouldn’t those who actively decide to opt for a flu shot be more apt to actually get one than those who passively accept the default?

Might there be a way to design for explicit decision-making that encourages people to feel better about actively making a choice? With this question in mind, researchers conducted a study to test how the design for an explicit choice might affect decision outcomes. Specifically, they were interested in comparing the outcomes of two approaches to obtaining an explicit choice from users regarding enrollment in a 401(k) plan (an employer-sponsored retirement plan), as shown below.

Example 1 provides two options:

- “I want to enroll in a 401(k) plan.”

- “I don’t want to enroll in a 401(k) plan.”

Example 2 also provides two options:

- “I want to enroll in a 401(k) plan and take advantage of the employer match.”

- “I don’t want to enroll in a 401(k) plan and don’t want to take advantage of the employer match.”

Would actual choice outcomes be influenced by which design users interacted with? In example 1, the two choices are weighted equally. That is, if the user doesn’t have a specific or compelling reason to choose one over the other, chances are that they may feel conflicted about which one to choose. Neither necessarily feels better or worse than the other. Example 2, on the other hand, is explicit about what the user will potentially gain or give up as a result of choosing an option.

Results of the research study show that enrollment in a program increased when options were “enhanced” with explicit mention of the implications of each choice, and levels of commitment and participation in the program also increased. But why would the wording of example 2 make such a difference in people’s choice? From a design perspective, stating what seems obvious about the implications of each option might seem unnecessary.

But it turns out that, because people are generally unlikely to seek out information to inform their decision, the additional wording makes a difference. Proactively seeking out information is work, after all, and research consistently reveals people’s considerable sensitivity to and avoidance of almost any amount of effort. Because of this, providing information within the options themselves can have a powerful impact on decision outcomes.

Aversion To Potential Loss

For many people who are not enrolled in a 401(k) plan, maintaining the status quo of being unenrolled doesn’t seem to incur any negative emotion, risk or “loss.” Life seems to roll on normally when one is not enrolled. Most people are aware, however, that participation in a 401(k) plan involves regular contributions to the plan — money that is no longer available for daily household expenses or other regular uses. And inherent to the act of investing is the potential for market downturns and losses incurred over the course of an investment. For these reasons, taking the step of enrolling in the plan (and potentially losing one’s investment) might feel a lot riskier than maintaining the status quo by not enrolling.

But when the costs associated with maintaining the status quo (for example, by remaining unenrolled in the plan) are made apparent and are framed as a loss (for example, loss of the employer match), then the decision to enroll in the plan feels more compelling and motivating. People are much more motivated by ways to avoid loss than to realize gains.

Consider what might happen if example 2 were framed differently:

- “I want to enroll in a 401(k) plan.”

- “I don’t want to enroll in a 401(k) plan and don’t want to take advantage of the employer match.”

Framing the options in this way does not remind users that they have something to gain by enrolling, only that they have something to lose by not enrolling. I suspect that users would still feel strongly motivated to enroll, simply because people give disproportionately greater weight to loss than to gain.

Real-World Examples

Research has demonstrated the power of design in enhancing explicit choices, but what about examples from the real world? One example we can look to is the US pharmaceutical company CVS/caremark, which enjoyed greater rates of enrollment for its automatic prescription-refilling program when users were required to choose between two options:

- “I prefer to order my own refills.”

- “I want to enroll in the ReadyFill@Mail (automatic prescription refill program).”

The first option reminds users that not enrolling for the auto-refill program incurs a cost — the cost of having to do the work of ordering one’s own refills. It turns out that 21.9% of users decided to enroll in the program with this design of explicit choices, compared to only 12.3% of those who encountered an opt-in design. And customers who encountered the explicit choice also ended up filling more prescriptions than those in the opt-in design. It seems that preference for the program was actually enhanced once people made a commitment to joining.

Examples From The Retail World

Enhanced explicit choice is effective because it reminds people what they will gain or lose as a result of making a certain choice. Some online shopping websites are leveraging the power of such “reminders.”

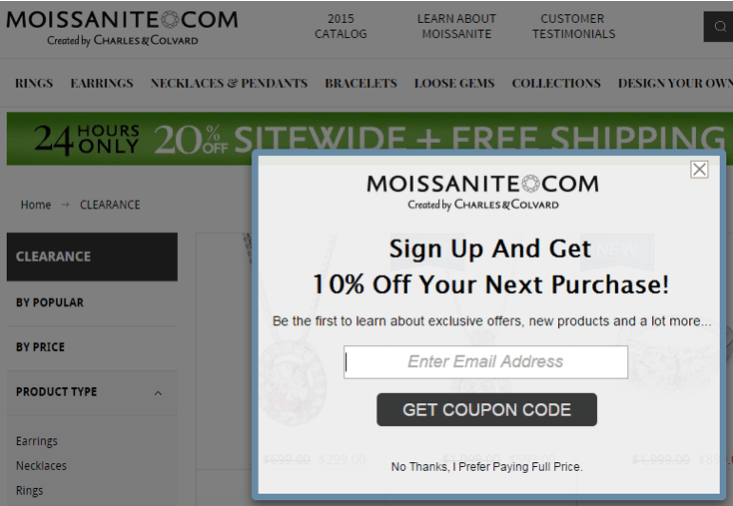

Moissanite is one such example. After a short time on its website, the user is presented with a modal requesting their email address in exchange for a 10% discount on their next purchase. Providing one’s email address, of course, incurs the “cost” of potentially getting unwanted email, etc. But at the bottom of the modal is a reminder of the cost of not signing up: “No thanks, I prefer paying full price.” Paying full price, of course, implies loss because the user could instead be enjoying a discounted price.

Consider another example, Bauble Box, which takes this concept a step further. After a short time on the website, the user is presented with the following modal, offering a 15% discount on one’s first purchase in exchange for an email address.

Noteworthy is the fact that there is no obvious way to close this box — for example, no “X” or “Close” (which would normally be located in the upper-right corner). To dismiss the box, the user must click the “Continue as guest” link towards the bottom of the box. And it might not be immediately apparent that this is a link.

The design seems to leverage these usability issues by forcing the user to hunt around for a way to dismiss the box, until they finally discover the “Continue as guest” link. Although this design risks user frustration, it nevertheless forces more time and attention towards the content of the box than users would ordinarily spend, increasing the likelihood that they will also notice the parenthetical text under the link, “(Without my 15% off coupon!)”

This design raises some interesting questions about how users perceive the experience and, consequently, whether this is a website they want to give their business to. To what extent might user frustration with the (intentional) usability issues adversely affect their perception of the company and the brand? At what point does the design cross the line to the dark side? These are important considerations, especially for companies that want to establish long-term relationships with their customers built on trust and delight.

Final Thoughts

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this article. We’ve seen that defaults are powerful because they provide a way for users to passively decide, thereby easing the difficulty and effort associated with decision-making. But we also know that, for a variety of reasons, providing a default option is not always appropriate. Sometimes, it’s better for users to make an explicit choice — especially when they are more likely to follow through with a decision and be more committed to taking action on it.

A primary lesson from this article is that merely reminding people what they stand to gain or lose as a result of making a particular choice can have a powerful impact on how they choose. And depending on the type of decision, how they choose can have significant implications for their lives. We’ve seen, too, that designing for explicit choice can manifest itself in different ways, depending on the subject matter and context of the experience.

It’s imperative to understand that the design matters. UX design professionals have a responsibility to understand how design itself influences — and sometimes even drives — user perception and behavior and, therefore, decision outcomes. To this end, the decisions we make as designers matter.

(cc, al, il)

(cc, al, il)

Front page image credits: Innovative Techniques To Simplify Sign-Ups and Log-Ins.