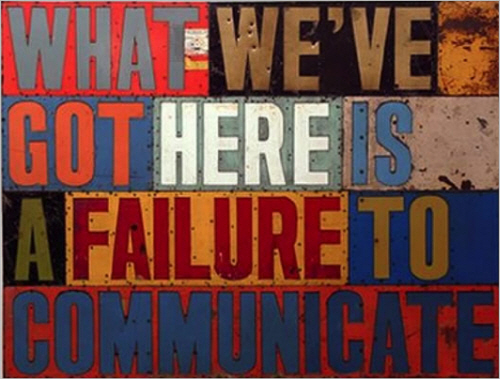

If you’ve ever worked at a company of any size, you’ve experienced it. Isolation. That feeling of being utterly alone in what you do.

Some people love it: the determination that comes from being a lone ranger, boldly going where no one has gone before. Others hate it: the despair that comes from slaving over a design only to see it disappear down a black hole of development, whereupon it emerges onto a website months later, unrecognizable from the pixels you put on the page with such painful precision.

Image credit: Ibrahim Iujaz

These are the perils of working in siloed environments, and it’s where many of us find ourselves today. We’re either terribly alone or terribly frustrated, depending on the particular variety of silo we find ourselves in. In this two-part series, I’ll explore the consequences of working in isolated environments, and how we can solve this problem by encouraging more collaborative cultures.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Web Designers, Don’t Do It Alone

- Why Great Products Need Great Collaboration

- How To Be A Samurai Designer

What Exactly Are We Talking About Here?

Silos in work environments usually come in two flavors:

- Lonely silos Lonely silos are made up of workers with no real connection to the outside world. This often happens at start-ups where the focus is more on getting something out the door than on doing it right. I mean, who has time for proper UX design when “we’re building [technology x] because [company y] hasn’t built it and [people z] need it?” (as Kyle Neath recently put it).

- Functional silos Functional silos feature workers who may be part of fantastic design teams. They have great whiteboard sessions, help each other out, enjoy their pizza Fridays… And yet, they have no real seat at the table when it comes to business strategy. Design happens painfully slow because it has to be signed off by 10 different people. And even then, there’s no guarantee that anything will be implemented the way the designers envisioned it.

Working in lonely silos and functional silos have two main consequences, both devastating to software development:

- No process This usually happens in lonely silos. It’s everyone for themselves. The company subscribes to the “release early, release often” approach, and so you won’t get bogged down with a formal development process, guidelines for functional specs or any of the stuff that big lame corporations busy themselves with.

- Too much process This usually occurs when functional silos get out of control. Organizations resort to putting hierarchies and processes in place to stop the “cowboy coding” madness. The science:art ratio in design shifts way too much to one side or the other. Functional specifications move into Microsoft Word templates that are 20 pages long before a single word of content is written. And sure enough, the cowboy madness stops. But it gets replaced with a different kind of madness: stagnation.

The Consequences Of Not Following A Design Or Development Process

When you work in an environment where silos result in no clear design or development process, the following often happens.

1. MVP Madness

We all know the concept of “Minimum Viable Product,” but revisiting Eric Reis’ definition would be useful:

The minimum viable product is that product which has just those features (and no more) that allow you to ship a product that resonates with early adopters; some of whom will pay you money or give you feedback.

Problem is, that last section of the definition often gets ignored. You know, the part about people paying you money. So this MVP idea can be taken too far, and a product can be released before there is a minimum viable understanding of what the thing is supposed to do (or who it’s supposed to be useful for). You could argue that the Color app is an example of this MVP madness (“It’s a photo app!” “No, it’s a data-mining app!” “Actually, it’s a local group-messaging search/recommendations app!”)

Perhaps the best example of this culture is the Lifepath sign-up page, which Dustin Curtis recently put up in what I’d like to believe is a deliberate and very effective attempt at MVP irony:

A lot of this problem would go away if we evolve MVP thinking into what Andrew Chen calls “Minimum Desirable Product”:

Minimum Desirable Product is the simplest experience necessary to prove out a high-value, satisfying product experience for users.

I think that definition would send a lot of MVPs back to the drawing board, and rightfully so.

2. No Significant Design Focus

The second consequence of a lack of process, particularly in start-ups, is that design can be the last thing on people’s minds. When you hear start-ups giving an overview of their staff, they often mention developers, marketers, and business development managers, but no designers.

There can obviously be legitimate business strategy reasons for those hiring decisions, but where it can become harmful is when ideas go from vision to code (and users) in one easy step, bypassing the principles of user-centered design completely. As Erika Hall puts it:

The floor of Silicon Valley is littered with the crumbling husks of great ideas — useful products and services that died in the shell before they hatched out of their impenetrable engineering-specified interfaces.

3. Endless Cycles

A third consequence of no-process development is that you never really know when you’re done. Not to make this about methodology, but this is one area where the “definition of done” concept in Scrum is extremely useful. If you don’t know when you’re ready to push something live, then the problems of MVP madness and lack of design are exacerbated.

Google Wave is a case in point. Listen to Douwe Osinga as he gives two good examples of MVPs done right before moving on to the problem with Google Wave:

Thinking big sounds great, but most big ideas start small and go from there. Google itself started from the notion that it would be interesting to look at back links for pages. Twitter started out as hardly more than a group SMS product that also works online. Facebook explicitly restricted themselves at first to one university.Wave is a case in point. Wave started with some fairly easy to understand ideas about online collaboration and communication. But in order to make it more general and universal, more ideas were added until the entire thing could only be explained in a 90 minute mind blowing demo that left people speechless but a little later wondering what the hell this was for.

The Consequences Of Having Too Much Design/Development Process

So that’s what can happen in a no-process environment. But what happens at the other end of the continuum, where process is king of the world?

1. Org-Structure Design

When you can sketch out an organization’s structure by looking at its home page, chances are it’s hopelessly lost in functional silos. I experienced this first-hand while working at eBay. I would sometimes run into the product manager for the home page in the morning, and he’d have no idea why his page looked the way it did on that particular day. Each day was an adventure to see what had changed on the page that he “owned.”

Don’t believe me? Below is an example of the eBay home page from about a year ago, with the teams responsible for each section of the page overlaid (they’ve since gone through a redesign that fixed this issue):

This is unfortunately one of the side effects of functional silos. You run the risk of losing any sense of holistic design direction on the website.

2. Design Monkeys

Another consequence of an over-reliance on process is that designers could become nothing more than monkeys, cranking out efficient, perfectly grid-aligned but completely uninspired designs on an assembly line. Wondering whether this is you? Here are some instructions you might recognize as a design monkey:

Don’t get me wrong: I believe in style guides, and I believe in design constraints. But when an organization becomes overly reliant on design rules, creativity is often the first thing out the door. Yes, design is much more than art (we’ll come back to this later), but it’s certainly not pure science either. Without the right injection of art and creativity, science gets boring and forgotten pretty quickly.

3. Tired Developers

Once process takes over an organization, the acronyms start. And arguably, the most feared of them all is PRD: the product requirements document. This usually takes the form of a Word template, with a two-page table of contents. It includes a solution to every single eventuality the software might ever encounter. It sucks the soul out of product managers and the life out of developers.

To use an example from a previous company, we once had a 23-page PRD to make some changes to our SiteCatalyst JavaScript implementation. And then the project didn’t happen. I shudder to think about the hours and hours of lost productivity that went into creating this document that never got used. People could have created things during that time. Instead, they sat in Microsoft Word.

The result? Tired developers. Developers who don’t want to code anymore because coding becomes 70% deciphering Word documents, 20% going back and forth on things that aren’t clear, and 10% actually coding.

How do you know that your developers are tired? Charles Miller quotes an ex-Google employee as describing what it means when a developer tells you that something is “non-trivial” sums it up pretty well:

It means impossible. Since no engineer is going to admit something is impossible, they use this word instead. When an engineer says something is “non-trivial,” it’s the equivalent of an airline pilot calmly telling you that you might encounter “just a bit of turbulence” as he flies you into a cat 5 hurricane.

Tired developers use the word “non-trivial,” or some variation thereof, a lot more than energized developers.

4. Distrust Between Teams

When people don’t live and breathe each other’s workflows, understanding the decisions they make is hard. And if you don’t understand the reason for someone’s decisions, distrust can creep in.

Functional silos that rely on too much process serve as fertile ground for distrust in relationships. A reliance on process can instill a false sense of security and the mistaken assumption that conversation and understanding are less important than proper documentation. This is particularly true in the complicated relationship between designers and developers. As Don Norman recently put it:

Designers evoke great delight in their work. Engineers provide utilitarian value. My original training was that of an engineer and I, too, produce practical, usable things. The problem is that the very practical, functional things I produce are also boring and ugly. Good designers would never allow boring and ugly to describe their work: they strive to produce delight. But sometimes that delightful result is not very practical, difficult to use and not completely functional. Practical versus delightful: Which do you prefer?

So, when designers and developers are not in the same room from the moment a project kicks off, or when design becomes prescriptive before thorough discussion has taken place and everyone has sweated the details together, the stage is set for the two worlds to collide. Breaking down these silos is the only way to design solutions that are practical and delightful.

5. Design by Committee

Not everyone can code, so they don’t go to developers telling them that their HTML needs to be more semantic. But everyone thinks they’re a designer, or at least has a gut feeling about design. They like certain colors or certain styles, and some people just really hate yellow. Because everyone has an emotional response to design and believes “it’s just like art,” they think they know enough about design to turn those personal preferences into feedback.

One of the first things we need to do to solve this problem is to teach people how to give better design feedback. Mike Monteiro gets to the crux of the issue in “Giving Better Design Feedback”:

First rule of design feedback: what you’re looking at is not art. It’s not even close. It’s a business tool in the making and should be looked at objectively like any other business tool you work with. The right question is not, “Do I like it?” but “Does this meet our goals?” If it’s blue, don’t ask yourself whether you like blue. Ask yourself if blue is going to help you sell sprockets. Better yet: ask your design team. You just wrote your first feedback question.

And how do we respond practically to the problems of design by committee? Smashing Magazine’s own article sums it up best:

The sensible answer is to listen, absorb, discuss, be able to defend any design decision with clarity and reason, know when to pick your battles and know when to let go.

Here are four principles I use in my day-to-day work to make that statement a reality:

- Respond to every piece of feedback. This is tiring, but essential. Regardless of how helpful it is, if someone took the time to give you feedback on a design, you need to respond to it.

- Note what feedback is being incorporated. Be open to good feedback. Don’t let pride get in the way of a design improvement. And let the person know what feedback is being incorporated.

- Explain why feedback is not being taken. If a particular piece of feedback is not being implemented, don’t just ignore it. Let the person know that you’ve thought about it, and explain the reason for not incorporating that feedback. They will be less likely to get upset at you if you explain clearly why you’re taking the direction you’re taking. And if you’re not sure how to defend the decision…

- Use the user experience validation stack. Read the post “Winning a User Experience Debate” for more detail. But in short, first try to defend a decision based on user evidence — actual user testing on the product. If that’s not available, go to Google and find user research that backs up the decision. In the absence of that, go back to design theory to explain your direction.

Summary, And Where We Go From Here

Ending an article on such a doom-and-gloom note feels a bit wrong. But maybe pausing here would be good so that we can all reflect on the issues that siloed development creates in our own organizations. As UX people, we’re taught to understand the problem first before trying to solve it, right? So, let’s do that. Did I miss any consequences? Anything you’d like to add or challenge about the consequences I’ve highlighted in this article?

We looked at the consequences of designing and developing software in isolated environments. Some people work in lonely silos where no process exists, while others work in functional silos where too much (or the wrong) process makes innovation and progress difficult.

So, how do we break down the artificial walls that keep us from creating great things together? How can organizations foster environments that encourage natural, unforced collaboration?

There are no quick fixes, but these are far from insurmountable problems. I propose the following five-level hierarchy as a solution:

There are no shortcuts to breaking down silos. You can’t fix the environment if the organization doesn’t understand the problem. You can’t improve the development process if the right environment doesn’t exist to enable healthy guidelines. You have to climb the pyramid brick by brick to the ultimate goal: better software through true collaboration.

Let’s look at each of these levels.

Level 1: Make Sure Everyone Understands The Problem

Photo credit: David Buckingham

Most organizational leaders would probably admit that collaboration is not as good as it should be, but they might try to solve the problem incorrectly. As Louis Rosenfeld recently said in “The Metrics of In-Betweenness”:

Many senior leaders recognize the silo problem, but they solve it the wrong way: if one hierarchical approach to organizing their business doesn’t work, try another hierarchy. Don’t like the old silos? Create new ones. This dark tunnel leads to an even darker pit: the dreaded — and often horrifically ineffective — reorg.

The first level is admitting that there’s a problem and that the current problem-solving methods just aren’t working. This isn’t about moving branches of the organizational tree around. It’s about planting the tree in more fertile ground to establish the right foundation in order to start looking for solutions.

Level 2: Empower Teams To Do Great Work

Once the organization is united around a common understanding of the problem, then the starting point for breaking down silos is to take a healthy look at the culture and work environments. Above all, the needs of makers (such as designers and developers) should be taken seriously by managers (those who direct and enable the work). Mike Monteiro takes on this issue by attacking the calendar in “The Chokehold of Calendars”:

Meetings may be toxic, but calendars are the superfund sites that allow that toxicity to thrive. All calendars suck. And they all suck in the same way. Calendars are a record of interruptions. And quite often they’re a battlefield over who owns whose time.

Paul Graham takes a more holistic view in “Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule.” He explains that managers break their days up into hour-long stretches of time, while makers need large blocks of time in order to focus:

When you’re operating on the maker’s schedule, meetings are a disaster. A single meeting can blow a whole afternoon, by breaking it into two pieces, each too small to do anything hard in. Plus you have to remember to go to the meeting. That’s no problem for someone on the manager’s schedule. There’s always something coming on the next hour; the only question is what. But when someone on the maker’s schedule has a meeting, they have to think about it.

Makers need long stretches of uninterrupted time to get things done, and get them done well. Most siloed environments don’t support this because of an insatiable need for everyone to agree on everything (more on this later). So first, helping managers understand why this is such a big deal for makers is important, so that the managers can effect cultural change.

Michael Lopp talks about this in his article “Managing Nerds.” Substitute the word “nerds” in this article with “designers and developers” (no offense intended). Michael describes how nerds are forever chasing two highs.

The first high is unraveling the knot: that moment when they figure out how to solve a particular problem (“Finally, a simple way to get users through this flow.”). But the second high is more important. This is when “complete knot domination” takes place — when they step away from the 10 unraveled knots, understand what created the knots and set their minds to making sure the knots don’t happen again (“OK, let’s build a UI component that can be used whenever this situation occurs.”).

Chasing the Second High is where nerds earn their salary. If the First High is the joy of understanding, the Second High is the act of creation. If you want your nerd to rock your world by building something revolutionary, you want them chasing the Second High.

And the way to help designers and developers chase the second high is to “obsessively protect both their time and space”:

The almost-constant quest of the nerd is managing all the crap that is preventing us from entering the Zone as we search for the Highs.

So, how do you change a culture built around meetings and interruptions? How do you understand what designers and developers need in order to be effective, and how do you relentlessly protect them from distractions? Here are two ways to start:

- Ask the makers what’s missing from their environment that would help them be more effective. Find out what your designers and developers need, and then make it happen. A quiet corner to work in? Sure. A bigger screen? Absolutely. No interruptions while the headphones are on? Totally fine. Whatever it takes to help them be as creative as possible and to be free to chase that second high.

- Start working on a better meeting culture. This one is a constant struggle for organizations of all sizes, and there are many ways to address it. I try to adhere to two simple rules. First, a meeting has to produce something: a wireframe, a research plan, a technical design, a strategic decision to change the road map, etc. Secondly, no status meetings. That’s what Google Docs and wikis are for (agile standups are an exception to this, for reasons best left to a separate article).

Level 3: Create A Better Design And Development Lifecycle

Once a team is optimized for creativity, then it becomes possible to build appropriate guidelines around that culture to take an idea from vision to shipped product. This includes the development process as well as the prioritization of projects, so that you only work on things that are important.

The Design And Development Process

Formalizing the design and development process is so critical: from the identification of user, business and technical needs, to the UX design cycle, to technical design and, ultimately, to development, QA and launch. By formalizing this process based on a common understanding of the needs of the business, the team will have no excuse for skipping the UX phase of a project because “it would take too long.” By providing different scenarios for whatever timelines are available, the team ensures that design and UX always remain a part of the development lifecycle.

But one particular aspect of the development process has a direct impact on organizational silos: ensuring the right balance between design and engineering, and how designers and developers work together. This isn’t explored enough, yet it can have far-reaching implications on the quality of a product.

Thomas Petersen describes the ideal relationship between designers and developers in “Developers Are From Mars, Designers From Venus”:

They are the developers who can design enough to appreciate what good design can do for their product even if it sometimes means having to deviate from the framework and put a little extra effort into customizing certain functionality. If they are really good developers they will actually anticipate that they have to deal with it and either use a framework that allows them be more flexible or improve the framework they prefer to work in.And they are the designers who learn how to think like a programmer when they design and develop an aesthetic that is better suited to deconstruction rather than composition. They know that composition in the Web world is not like composition in the print world and that what they are really doing is solving problems for customers, not manifestations of their creative ego.

Beyond the usual discussion of whether designers should be able to code, one of the main causes of bad blood between the groups is that developers are rarely asked what they need in order to write the best possible code. Designers should always ask their development teams two questions:

- “How would you like to contribute to the product development process?” It is amazing how few people actually ask this question, as is how the opinions of the people who understand the product at its most detailed level often don’t have a voice in ideation or prioritization. Any cycle that doesn’t include developers from the beginning will likely fail, because the conflict between design and utility cannot be resolved with detailed specifications. It can be resolved only around a table, with plenty of paper to draw on and time to argue about the best way to do things. Of course, designers need time on their own to create, but developers need to be given a chance to contribute to the product that they’re building in a way they’re comfortable with.

- “What information do you need to start coding?” The theoretical discussion about low-fidelity versus high-fidelity mock-ups or prototypes is largely misguided when it comes to real-world development. The goal is right-fidelity specifications, and that all depends on the maturity of the application you’re working on and the style of the developer. Some developers need perfect PSDs before they start coding; others are fine with back-of-the-napkin sketches along with a solid UI component library. Find out what they need, and provide just that — anything more than what they need will not get looked at, and that’s when tempers can really flare up.

Bringing such diverse worlds together is hard work. But, in “So Happy Together: Designers and Engineers,” Dave Gustafson warns what might happen if you don’t invest in this:

What’s the alternative to this kind of collaboration? Keeping design and engineering separate, where the pass-off from one to the other is aptly called “throwing it over the wall.” Designers may enjoy an unhindered blue-sky design process, but they’ll likely be disappointed with what actually gets made. Without engineers in the design process, there are bound to be some unrealistic features in the concept — and without an understanding of the designers’ intentions and priorities, engineers are likely to compromise the design with changes to meet cost goals. Some money may have been saved on the engineering and manufacturing — but not enough to offset a product that misses the mark.

The Prioritization Process

When there is no clear development process, “prioritization” can end up being a complex algorithm consisting of the last email request sent, the job title of the requestor, and proximity to the development team. This is no way to build a product. One way to address the difficulties of prioritization is through the concept of a “product council.”

At a start-up, the entire company could make up this group — even if it’s a group of one. In large companies, the group should include the CEO and the VPs of each department, including marketing, product, engineering, support, etc. The name is not important — the purpose is. The product council would have weekly or by-weekly meetings with two goals:

- Review the current product road map to assess whether the right priorities are being addressed.

- Introduce new ideas (if any) that have come up during the week and discuss business cases and priorities.

This meeting would have several very positive outcomes:

- It would give the management team complete insight into what the product or design team is working on, and would allow for anyone to make a case for a change in priorities. This eliminates the vast majority of the politics you see at many organizations, and it frees up the teams to do what they do best: execute.

- No one in the company would be able to go straight to a designer or developer to sneak things onto the road map. The user, technical or business impact of every big idea must be demonstrated.

- It would prevent scope creep. Nothing would be put on the road map without something else moving out or down. This is absolutely critical to the development cycle.

From there, projects would move to small dedicated teams, which would have complete ownership of the design and implementation. The product council sets the priorities, not the details of implementation — those are up to the teams themselves. I’m always reminded of what Jocelyn K. Glei says in her excellent article “What Motivates Us to Do Great Work?”:

For creative thinkers, [there are] three key motivators: autonomy (self-directed work), mastery (getting better at stuff), and purpose (serving a greater vision). All three are intrinsic motivators.… In short, give your team members what they need to thrive, and then get out of the way.

In pursuit of collaboration, we run the risk of overshooting our target and gaining the false sense of security that “consensus” brings. Consensus too often results in mediocre products, because no one really gets what they want, so the result is a giant compromise. Marty Cagan says this very well in his article “Consensus vs. Collaboration”:

In consensus cultures people are rarely excited or supportive. Mostly because they are very frustrated at how slow things move, how risk-averse the company is, how hard it is to make a decision, and especially how unimpressive the products are.

So, even though everyone agreeing on something is great, having someone be responsible for the decisions in that particular project is infinitely more important. This person does not do all the work, but rather is the one who owns the product’s fate — its successes and failures.

In many organizations, this person is the product manager, but it doesn’t have to be. Whoever it is, the role should be clearly defined and well communicated to the rest of the organization. The role is not that of a dictator, but of a diplomat, working with UX, business functions and engineering to build products that are driven by user, business and technology needs.

Level 4: Communicate Better

Once the appropriate guidelines are in place and the teams are working effectively, it’s time to root out any other causes of mistrust that might still exist. And one of the best ways to build trust in an organization is to eradicate secrets.

I am huge believer in full transparency, and I see little need in keeping any relevant information about a project from anyone. (The prerequisite? Hire trustworthy employees!)

If plans, progress and problems are published for all to see, there is no need to hide anything and no need to play politics to get things done. Here are just some of the things that should be published on a public wiki for anyone to view and comment on (written from the perspective of a UX team):

- Roles and responsibilities of the product and UX teams.

- How road-map planning and the prioritization process work.

- How the product development process works, including (critically) where UX fits into even the smallest projects.

- The goals and success metrics for every product line.

Publish everywhere, invite anyone. The tools at our disposal make this so easy, from Dropbox and Google Docs to ConceptShare and Campfire. There is no excuse for keeping things to ourselves.

Level 5: Prove That It Works

When the groundwork is laid for silos to start crumbling down, one last piece of dynamite will blow it all up: it’s time to start proving that it works. People will believe you for only so long if you say, “Trust me, this is the right thing to do!” At some point you have to show them the money.

A common theme throughout this series has been that better collaboration results in better software. The only way to cement these changes into the organizational culture is to show that you’re actually shipping a better product because of it.

Here’s what I do to demonstrate the business value of a collaborative development process that includes a tightly integrated UX cycle:

- Share case studies from other companies or projects that clearly show the business benefits of working this way. Showing that it’s been successful elsewhere should buy enough time and resources for the team to put in place its plans to follow a proper collaborative design and development process in one or more of its projects.

- Start on a project where changes can be measured by an improvement in one of the three A’s of revenue generation:

- Acquisition. Getting new users to sign up for your product.

- Activation. Getting those new users to make their first purchase.

- Activity. Getting those first-time purchasers to come back for more.

- Benchmark well before the start of the project, and set clear goals to measure the success of the project.

- Follow through on the commitment to collaboration, and measure your results. See “How to Measure the Effectiveness of Web Designs” for ideas on which measurement tools to use.

- Publish your metrics widely so that everyone in the organization can see the results. And don’t hide the failures. There will be failures — the trick is to own those mistakes, learn from them and get better.

Summary (aka “Whose Job Is It, Anyway?”)

So, whose job is it to break down organizational silos and build a collaborative development process?

Guess what? It’s your job. Whether you’re a designer, developer or manager, this isn’t something that someone else will get around to — if it was, then it would have happened already. Building collaboration is best done through a groundswell in the organization, led by the makers, the people who build the actual product. It might be difficult, but I hope there are enough case studies and examples in this series to help you get started on this journey of organizational change.

Collaboration only works if everyone in the organization is open about their processes and workflows, without fear of being judged unfairly. Arguments over what’s right and how to do things differently will happen. And they should — it’s the only way to get better at what we do.

Building collaborative environments is not easy, because change management is not easy. But the positive outcomes of doing this far outweigh the pain of making it happen. You’ll end up with happy, creative teams that feel a sense of ownership over what they’re building and a sense of pride in its quality.

I often remind my team that we are judged on the products we ship, not on the number of times we ask for help along the way. So, what possible reason could there be not to collaborate and create a better product — because it will make us all look better in the end anyway? (Hint: there isn’t one.)

Go. Make it happen.

(al)

(al)