If you’re a front-end developer following the evolution of single page applications (SPA), it’s likely you’ve heard of Elm, the functional language that inspired Redux. If you haven’t, it’s a compile-to-JavaScript language comparable with SPA projects like React, Angular, and Vue.

Like those, it manages state changes through its virtual dom aiming to make the code more maintainable and performant. It focuses on developer happiness, high-quality tooling, and simple, repeatable patterns. Some of its key differences include being statically-typed, wonderfully helpful error messages, and that it’s a functional language (as opposed to Object-Oriented).

My introduction came through a talk given by Evan Czaplicki, Elm’s creator, on his vision for the front-end developer experience and in turn, the vision for Elm. As someone also focused on the maintainability and usability of front-end development, his talk really resonated with me. I tried Elm in a side-project a year ago and continue to enjoy both its features and challenges in a way I haven’t since I first started programming; I’m a beginner all over again. In addition, I find myself able to apply many of Elm’s practices in other languages.

Developing Dependency Awareness

Dependencies are everywhere. By reducing them, you can improve the likelihood that your site will be usable by the greatest number of people in the widest variety of scenarios.Read a related article →

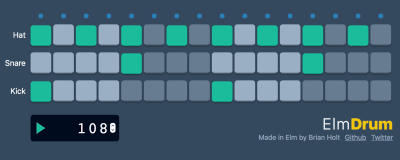

In this two-part article, we’ll build a step sequencer to program drum beats in Elm, while showcasing some of the language’s best features. Today, we’ll walk through the foundational concepts in Elm, i.e. getting started, using types, rendering views, and updating state. The second part of this article will then dive into more advanced topics, such as handling large refactors easily, setting up recurring events, and interacting with JavaScript.

Play with the final project here, and check out its code here.

Getting Started With Elm

For following along in this article, I recommend using Ellie, an in-browser Elm developer experience. You don’t need to install anything to run Ellie, and you’re able to develop fully-functional applications in it. If you’d rather install Elm on your computer, the best way to get set up is by following the official getting started guide.

Throughout this article, I’ll link to the work-in-progress Ellie versions, though I developed the sequencer locally. And while CSS can be written entirely in Elm, I’ve written this project in PostCSS. This requires a little bit of configuration to the Elm Reactor for local development in order to have styles loaded. For the sake of brevity, I won’t touch on styles in this article, but the Ellie links include all minified CSS styles.

Elm is a self-contained ecosystem that includes:

- Elm Make

For compiling your Elm code. While Webpack is still popular for productionizing Elm projects alongside other assets, it's not required. In this project, I've opted to exclude Webpack, and rely onelm maketo compile the code. - Elm Package

A package manager comparable to NPM for using community-created packages/modules. - Elm Reactor

For running an automatically-compiling development server. More notable, it includes the Time Traveling Debugger making it easy to step through your application's states and replay bugs. - Elm Repl

For writing or testing out simple Elm expressions in the terminal.

All Elm files are considered modules. The beginning lines of any file will include module FileName exposing (functions) where FileName is the literal filename, and functions are the public functions you want to make accessible to other modules. Immediately after the module definition are imports from external modules. The rest of the functions follow.

module Main exposing (main)

import Html exposing (Html, text)

main : Html msg

main =

text "Hello, World!"

This module, named Main.elm, exposes a single function, main, and imports Html and text from the Html module/package. The main function consists of two parts: the type annotation and the actual function. Type annotations can be thought of as function definitions. They state the argument types and the return type. In this case, ours states the main function takes no arguments and returns Html msg. The function itself renders a text node containing “Hello, World.”

To pass arguments to a function, we add space-separated names before the equal sign in the function. We also add the argument types to the type annotation, in the order of the arguments, followed by an arrow.

add2Numbers : Int -> Int -> Int

add2Numbers first second =

first + second

In JavaScript, a function like this is comparable:

function add2Numbers(first, second) {

return first + second;

}

And in a Typed language, like TypeScript, it looks like:

function add2Numbers(first: number, second: number): number {

return first + second;

}

add2Numbers takes two integers and returns an integer. The last value in the annotation is always the return value because every function must return a value. We call add2Numbers with 2 and 3 to get 5 like add2Numbers 2 3.

Just as you bind React components, we need to bind compiled Elm code to the DOM. The standard way to bind is to call embed() on our module and pass the DOM element into it.

<script>

const container = document.getElementById('app');

const app = Elm.Main.embed(container);

<script>

Though our app doesn’t really do anything, we have enough to compile our Elm code and render text. Check it out on Ellie and try changing the arguments to add2Numbers on line 26.

Data Modeling With Types

Coming from a dynamically-typed language like JavaScript or Ruby, types may seem superfluous. Those languages determine what type functions take from the value being passed in during run time. Writing functions is generally considered faster, but you lose the security of ensuring your functions can properly interact with each other.

In contrast, Elm is statically-typed. It relies on its compiler to ensure values passed to functions are compatible before run time. This means no runtime exceptions for your users, and is how Elm can make its “no runtime exceptions” guarantee. Where type errors in many compilers can be especially cryptic, Elm focuses on making them easy to understand and correct.

Elm makes getting started with types very friendly. In fact, Elm’s type inference is so good you can skip writing annotations until you’re more comfortable with them. If you’re brand new to types, I recommend relying on the compiler’s suggestions rather than trying to write them yourself.

Let’s get started modeling our data using types. Our step sequencer is a visual timeline of when a particular drum sample should play. The timeline consists of tracks, each assigned with a specific drum sample and the sequence of steps. A step can be considered a moment in time or a beat. If a step is active, the sample should be triggered during playback, and if the step is inactive, the sample should stay silent. During playback, the sequencer will move through each step playing the samples of the active steps. The playback speed is set by the Beats Per Minute (BPM).

Modeling Our Application in JavaScript

To get a better idea of our types, let’s consider how to model this drum sequencer in JavaScript. There are an array of tracks. Each track object contains information about itself: the track name, the sample/clip that will trigger, and the sequence of step values.

tracks: [

{

name: "Kick",

clip: "kick.mp3",

sequence: [On, Off, Off, Off, On, etc...]

},

{

name: "Snare",

clip: "snare.mp3",

sequence: [Off, Off, Off, Off, On, etc...]

},

etc...

]

We need to manage the playback state between playing and stopped.

playback: "playing" || "stopped"

During playback, we need to determine which step should be played. We should also consider playback performance, and rather than traversing each sequence in each track each time a step is incremented; we should reduce all of the active steps into a single playback sequence. Each collection within the playback sequence represents all the samples that should be played. For example, ["kick", "hat"] means the kick and hi-hat samples should play, whereas ["hat"] means only the hi-hat should play. We also need each collection to constrain uniqueness to the sample, so we don’t end up with something like ["hat", "hat", "hat"].

playbackPosition: 1

playbackSequence: [

["kick", "hat"],

[],

["hat"],

[],

["snare", "hat"],

[],

["hat"],

[],

...

],

And we need to set the pace of playback, or the BPM.

bpm: 120

Modeling With Types In Elm

Transcribing this data into Elm types is essentially describing what we expect our data to be made of. For instance, we’re already referring to our data model as model, so we call it that with a type alias. Type aliases are used to make code easier to read. They’re not a primitive type like a boolean or integer; they’re simply names we give a primitive type or data structure. Using one, we define any data that follows our model structure as a model rather than as an anonymous structure. In many Elm projects, the main structure is named Model.

type alias Model =

{ tracks : Array Track

, playback : Playback

, playbackPosition : PlaybackPosition

, bpm : Int

, playbackSequence : Array (Set Clip)

}

Though our model looks a bit like a JavaScript object, it’s describing an Elm Record. Records are used to organize related data into several fields which have their own type annotations. They’re easy to access using field.attribute, and easy to update which we’ll see later. Objects and records are very similar, with a few key differences:

- Non-existent fields can’t be called

- Fields will never be

nullorundefined thisandselfcan’t be used

Our collection of tracks can be made up of one of three possible types: Lists, Arrays, and Sets. In short, Lists are non-indexed general-use collections, Arrays are indexed, and Sets only contain unique values. We need an index to know which track step has been toggled, and since arrays are indexed, it’s our best pick. Alternatively, we could add an id to the track and filter from a List.

In our model, we’ve typeset tracks to an array of track, another record: tracks : Array Track. Track contains the information about itself. Both name and clip are strings, but we’ve typed aliased clip because we know it will be referenced elsewhere in the code by other functions. By aliasing it, we begin to create self-documenting code. Creating types and type aliases allow developers to model the data model to the business model, creating ubiquitous language.

type alias Track =

{ name : String

, clip : Clip

, sequence : Array Step

}

type Step

= On

| Off

type alias Clip =

String

We know the sequence will be an array of on/off values. We could set it as an array of booleans, like sequence : Array Bool, but we’d miss an opportunity to express our business model! Considering step sequencers are made of steps, we define a new type called Step. A Step could be a type alias for a boolean, but we can go one step further: Steps have two possible values, on and off, so that’s how we define the union type. Now steps can only ever be On or Off, making all other states impossible.

We define another type for Playback, an alias for PlaybackPosition, and use Clip when defining playbackSequence as an Array containing sets of Clips. BPM is assigned as a standard Int.

type Playback

= Playing

| Stopped

type alias PlaybackPosition =

Int

While there’s a little more overhead in getting started with types, our code is much more maintainable. It’s self-documenting and uses ubiquitous language with our business model. The confidence we gain in knowing our future functions will interact with our data in a way we expect, without requiring tests, is well worth the time it takes to write an annotation. And, we could rely on the compiler’s type inference to suggest the types so writing them is as simple as copying and pasting. Here’s the full type declaration.

Using The Elm Architecture

The Elm Architecture is a simple state management pattern that’s naturally emerged in the language. It creates focus around the business model and is highly scalable. In contrast to other SPA frameworks, Elm is opinionated about its architecture — it’s the way all applications are structured, which makes on-boarding a breeze. The architecture consists of three parts:

- The model, containing the state of the application, and the structure which we type aliased model

- The update function, which updates the state

- And the view function, which renders the state visually

Let’s begin building our drum sequencer learning the Elm Architecture in practice as we go. We’ll begin by initializing our application, rendering the view, then updating the application state. Coming from a Ruby background, I tend to prefer shorter files and split my Elm functions into modules though it’s very normal to have large Elm files. I’ve created a starting point on Ellie, but locally I’ve created the following files:

- Types.elm, containing all the type definitions

- Main.elm, which initializes and runs the program

- Update.elm, containing the update function that manages state

- View.elm, containing Elm code to render into HTML

Initializing Our Application

It’s best to start small, so we reduce the model to focus on building a single track containing steps that toggle off and on. While we already think we know the entire data structure, starting small allows us to focus on rendering tracks as HTML. It reduces complexity and You Ain’t Gonna Need It code. Later, the compiler will guide us through refactoring our model. In Types.elm file, we keep our Step and Clip types but change the model and track.

type alias Model =

{ track : Track

}

type alias Track =

{ name : String

, sequence : Array Step

}

type Step

= On

| Off

type alias Clip =

String

To render Elm as HTML, we use the Elm Html package. It has options to create three types of programs which build upon each other:

- Beginner Program A reduced program that excludes side-effects and is especially useful for learning the Elm Architecture.

- Program The standard program that handles side-effects, useful for working with databases or tools that exist outside of Elm.

- Program With Flags An extended program that can initialize itself with real data instead of default data.

It’s a good practice to use the simplest type of program possible because it’s easy to change it later with the compiler. This is a common practice when programming in Elm; use only what you need and change it later. For our purposes, we know we need to deal with JavaScript, which is considered a side-effect, so we create an Html.program. In Main.elm we need to initialize the program by passing functions to its fields.

main : Program Never Model Msg

main =

Html.program

{ init = init

, view = view

, update = update

, subscriptions = always Sub.none

}

Each field in the program passes a function to the Elm Runtime, which controls our application. In a nutshell, the Elm Runtime:

- Starts the program with our initial values from

init. - Renders the first view by passing our initialized model into

view. - Continually re-renders the view when messages are passed to

updatefrom views, commands, or subscriptions.

Locally, our view and update functions will be imported from View.elm and Update.elm respectively, and we’ll create those in a moment. subscriptions listen for messages to cause updates, but for now, we ignore them by assigning always Sub.none. Our first function, init, initializes the model. Think of init like the default values for the first load. We define it with a single track named “kick” and a sequence of Off steps. Since we’re not getting asynchronous data, we explicitly ignore commands with Cmd.none to initialize without side-effects.

init : ( Model, Cmd.Cmd Msg )

init =

( { track =

{ sequence = Array.initialize 16 (always Off)

, name = "Kick"

}

}

, Cmd.none

)

Our init type annotation matches our program. It’s a data structure called a tuple, which contains a fixed number of values. In our case, the Model and commands. For now, we always ignore commands by using Cmd.none until we’re ready to handle side-effects later. Our app renders nothing, but it compiles!

Rendering Our Application

Let’s build our views. At this point, our model has a single track, so that’s the only thing we need to render. The HTML structure should look like:

<div class="track">

<p class "track-title">Kick</p>

<div class="track-sequence">

<button class="step _active"></button>

<button class="step"></button>

<button class="step"></button>

<button class="step"></button>

etc...

</div>

</div>

We’ll build three functions to render our views:

- One to render a single track, which contains the track name and the sequence

- Another to render the sequence itself

- And one more to render each individual step button within the sequence

Our first view function will render a single track. We rely on our type annotation, renderTrack : Track -> Html Msg, to enforce a single track passed through. Using types means we always know that renderTrack will have a track. We don’t need to check if the name field exists on the record, or if we’ve passed in a string instead of a record. Elm will not compile if we try to pass anything other than Track to renderTrack. Even better, if we make a mistake and accidentally try to pass anything other than a track to the function, the compiler will give us friendly messages to point us in the right direction.

renderTrack : Track -> Html Msg

renderTrack track =

div [ class "track" ]

[ p [ class "track-title" ] [ text track.name ]

, div [ class "track-sequence" ] (renderSequence track.sequence)

]

It might seem obvious, but all Elm is Elm, including writing HTML. There isn’t a templating language or abstraction in order to write HTML — it’s all Elm. HTML elements are Elm functions, which take the name, a list of attributes, and a list of children. So div [ class "track" ] [] outputs <div class="track"></div>. Lists are comma-separated in Elm, so adding an id to the div would look like div [ class "track", id "my-id" ] [].

The div wrapping track-sequence passes the track’s sequence to our second function, renderSequence. It takes a sequence and returns a list of HTML buttons. We could keep renderSequence in renderTrack to skip the additional function, but I find breaking functions into smaller pieces much easier to reason about. In addition, we get another opportunity to define a stricter type annotation.

renderSequence : Array Step -> List (Html Msg)

renderSequence sequence =

Array.indexedMap renderStep sequence

|> Array.toList

We map over each step in the sequence and pass it into the renderStep function. In JavaScript mapping with an index would be written like:

sequence.map((node, index) => renderStep(index, node))

Compared to JavaScript, mapping in Elm is nearly reversed. We call Array.indexedMap, which takes two arguments: the function to be applied in the map (renderStep), and the array to map over (sequence). renderStep is our last function and it determines whether a button is active or inactive. We use indexedMap because we need to pass down the step index (which we use as an ID) to the step itself in order to pass it to the update function.

renderStep : Int -> Step -> Html Msg

renderStep index step =

let

classes =

if step == On then

"step _active"

else

"step"

in

button

[ class classes

]

[]

renderStep accepts the index as its first argument, the step as the second, and returns rendered HTML. Using a let...in block to define local functions, we assign the _active class to On Steps, and call our classes function in the button attributes list.

Updating Application State

At this point, our app renders the 16 steps in the kick sequence, but clicking doesn’t activate the step. In order to update the step state, we need to pass a message (Msg) to the update function. We do this by defining a message and attaching it to an event handler for our button.

In Types.elm, we need to define our first message, ToggleStep. It will take an Int for the sequence index and a Step. Next, in renderStep, we attach the message ToggleStep to the button’s on click event, along with the sequence index and the step as arguments. This will send the message to our update function, but at this point, the update won’t actually do anything.

type Msg

= ToggleStep Int Step

renderStep index step =

let

...

in

button

[ onClick (ToggleStep index step)

, class classes

]

[]

Messages are regular types, but we defined them as the type to cause updates, which is the convention in Elm. In Update.elm we follow the Elm Architecture to handle the model state changes. Our update function will take a Msg and the current Model, and return a new model and potentially a command. Commands handle side-effects, which we’ll look into in part two. We know we’ll have multiple Msg types, so we set up a pattern-matching case block. This forces us to handle all our cases while also separating state flow. And the compiler will be sure we don’t miss any cases that could change our model.

Updating a record in Elm is done a little differently than updating an object in JavaScript. We can’t directly change a field on the record like record.field = * because we can’t use this or self, but Elm has built-in helpers. Given a record like brian = { name = "brian" }, we can update the name field like { brian | name = "BRIAN" }. The format follows { record | field = newValue }.

This is how to update top-level fields, but nested fields are trickier in Elm. We need to define our own helper functions, so we’ll define four helper functions to dive into nested records:

- One to toggle the step value

- One to return a new sequence, containing the updated step value

- Another to pick which track the sequence belongs to

- And one last function to return a new track, containing the updated sequence which contains the updated step value

We start with ToggleStep to toggle the track sequence’s step value between On and Off. We use a let...in block again to make smaller functions within the case statement. If the step is already Off, we make it On, and vice-versa.

toggleStep =

if step == Off then

On

else

Off

toggleStep will be called from newSequence. Data is immutable in functional languages, so rather than modifying the sequence, we’re actually creating a new sequence with an updated step value to replace the old one.

newSequence =

Array.set index toggleStep selectedTrack.sequence

newSequence uses Array.set to find the index we want to toggle, then creates the new sequence. If set doesn’t find the index, it returns the same sequence. It relies on selectedTrack.sequence to know which sequence to modify. selectedTrack is our key helper function used so we can reach into our nested record. At this point, it’s surprisingly simple because our model only has a single track.

selectedTrack =

model.track

Our last helper function connects all the rest. Again, since data is immutable, we replace our entire track with a new track that contains a new sequence.

newTrack =

{ selectedTrack | sequence = newSequence }

newTrack is called outside of the let...in block, where we return a new model, containing the new track, which re-renders the view. We’re not passing side-effects, so we use Cmd.none again. Our entire update function looks like:

update : Msg -> Model -> ( Model, Cmd Msg )

update msg model =

case msg of

ToggleStep index step ->

let

selectedTrack =

model.track

newTrack =

{ selectedTrack | sequence = newSequence }

toggleStep =

if step == Off then

On

else

Off

newSequence =

Array.set index toggleStep selectedTrack.sequence

in

( { model | track = newTrack }

, Cmd.none

)

When we run our program, we see a rendered track with a series of steps. Clicking on any of the step buttons triggers ToggleStep, which hits our update function to replace the model state.

As our application scales, we’ll see how the Elm Architecture’s repeatable pattern makes handling state simple. The familiarity in its model, update, and view functions helps us focus on our business domain and makes it easy to jump into someone else’s Elm application.

Taking A Break

Writing in a new language requires time and practice. The first projects I worked on were simple TypeForm clones that I used to learn Elm syntax, the architecture, and functional programming paradigms. At this point, you’ve already learned enough to do something similar. If you’re eager, I recommend working through the Official Getting Started Guide. Evan, Elm’s creator, walks you through motivations for Elm, syntax, types, the Elm Architecture, scaling, and more, using practical examples.

In part two we’ll dive into one of Elm’s best features: using the compiler to refactor our step sequencer. In addition, we’ll learn how to handle recurring events, using commands for side-effects, and interacting with JavaScript. Stay tuned!

(da, ra, il)

(da, ra, il)