(This is a sponsored post). Once someone starts using your app, they need to know where to go and how to get there at any point. Good navigation is a vehicle that takes users where they want to go. But establishing good navigation is a challenge on mobile due to the limitations of the small screen and the need to prioritize content over chrome.

Different navigation patterns have been devised to solve this challenge in different ways, but they all suffer from a variety of usability problems. In this article, we’ll examine five basic navigation patterns for mobile apps and describe the strengths and weaknesses of each of them. If you’d like to add some patterns and spice up your designs, you can download and test Adobe XD for free and get started right away.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- How To Design Better Buttons

- The Golden Rules Of Bottom Navigation Design

- How To Design Error States For Mobile Apps

- How Functional Animation Helps Improve User Experience

Hamburger Menu

Screen space is a precious commodity on mobile, and the hamburger menu (or side drawer) is one of the most popular mobile navigation patterns for helping you save it. The drawer panel allows you to hide the navigation beyond the left edge of the screen and reveal it only upon a user’s action.

When To Use

The main downside of the hamburger menu is its low discoverability, and it’s not recommended as the main navigation menu. However, this pattern might be an appropriate solution for secondary navigation options. Secondary navigation options are destinations or features that are important for users only in certain circumstances. Being secondary, they can be relegated to less prominent visual placement, as long as users can quickly find a utility when they need it. By hiding these options behind the hamburger icon, designers avoid overwhelming users with too many options.

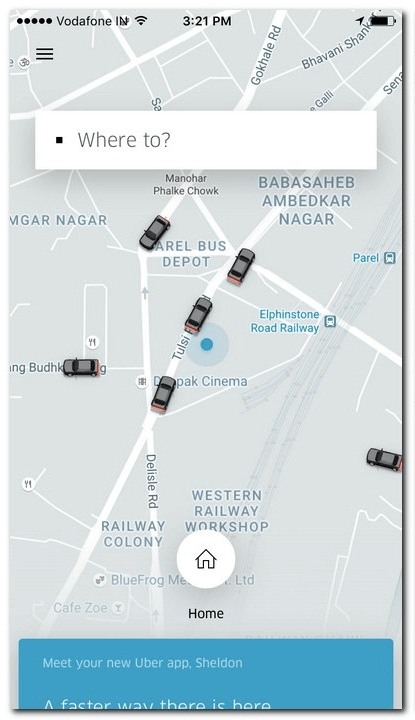

Uber uses a hamburger icon for this purpose. Because everything about the main screen of the Uber app is focused on requesting a car, there’s no need to display secondary options such as “Payment,” “History” or “Settings.” The normal user flow doesn’t include these actions, and so they can be hidden behind the hamburger icon.

Pros

- Large number of navigation options

The main advantage of the navigation menu is that it can accommodate a fairly large number of navigation options in a tiny space. - Clean design

The hamburger menu allows the designer to free up screen real estate by shifting options off screen into a side menu. This pattern can be particularly useful if you want the user to focus on the main content.

Cons

- Less discoverable

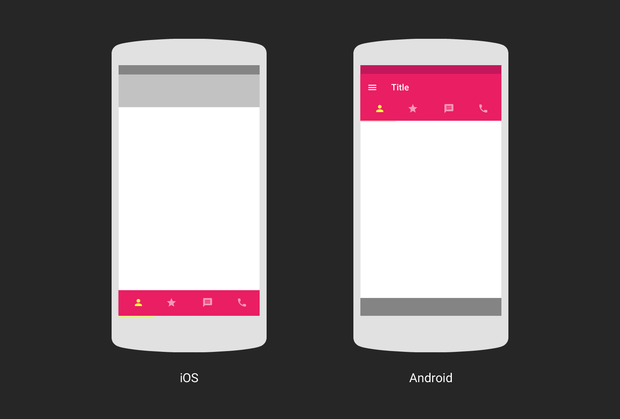

What’s out of sight is out of mind. When navigation is hidden, users are less likely to use it. While this type of navigation is becoming standard and many mobile users are familiar with it, many people still simply don’t think to open it. - Clashes with platform navigation rules

The hamburger menu has become almost a standard on Android (the pattern has the name “navigation drawer” in material design), but in iOS it simply cannot be implemented without clashing with basic navigation elements, and this could overload the navigation bar.

(Image: lmjabreu) - The hamburger icon hides context. The hamburger menu doesn’t communicate the current location at a glance: Surfacing information about the current location is harder because it’s only visible when the person clicks on the hamburger icon.

Out of sight, out of mind. The hamburger menu hides the user’s current location in the app. - Extra action is required to move to the target destination. Reaching a particular page usually takes at least two taps (one tap on the menu icon and another on the target option).

Tips

- Prioritize the navigation options. If the navigation is complex, hiding it won’t make it user-friendly. A lot of practical examples clearly show that exposing menu options in a more visible way increases engagement and user satisfaction. Ask yourself, What’s important enough to be visible on mobile? Answering that question will require an understanding of what matters to your users.

Redbooth’s move from a hamburger menu to a bottom tab bar resulted in increased user sessions. (Image: LukeW) - Consider using tabs or a tab bar if you have a limited number of high-priority navigation options.

YouTube makes the main pieces of core functionality available with one tap, allowing rapid switching between features. (Source: Luke Wroblewski) (View large version) - Review your information architecture. Good apps are highly focused. So, if you have one complex app, you could split its functionality into two (or more) simple apps. Facebook released its Messenger app in order to solve the problem of complexity. The reduced functionality results in a reduced set of menu options, and less need for a hamburger menu.

Tab Bar

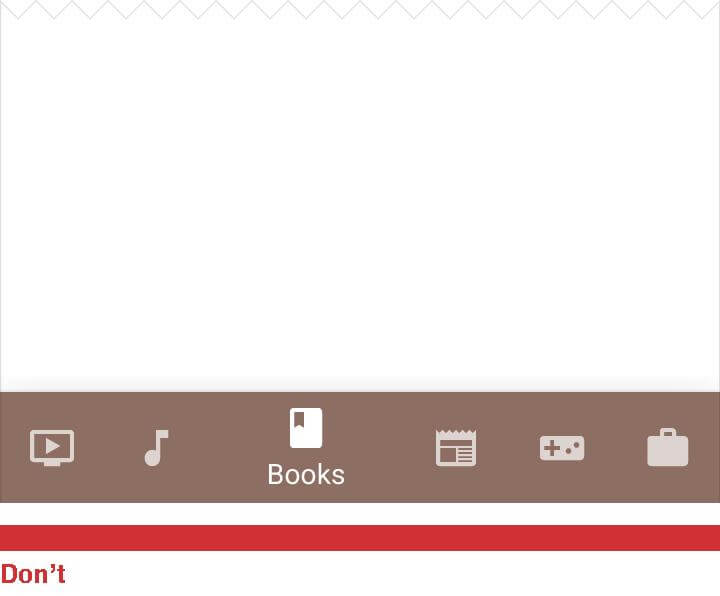

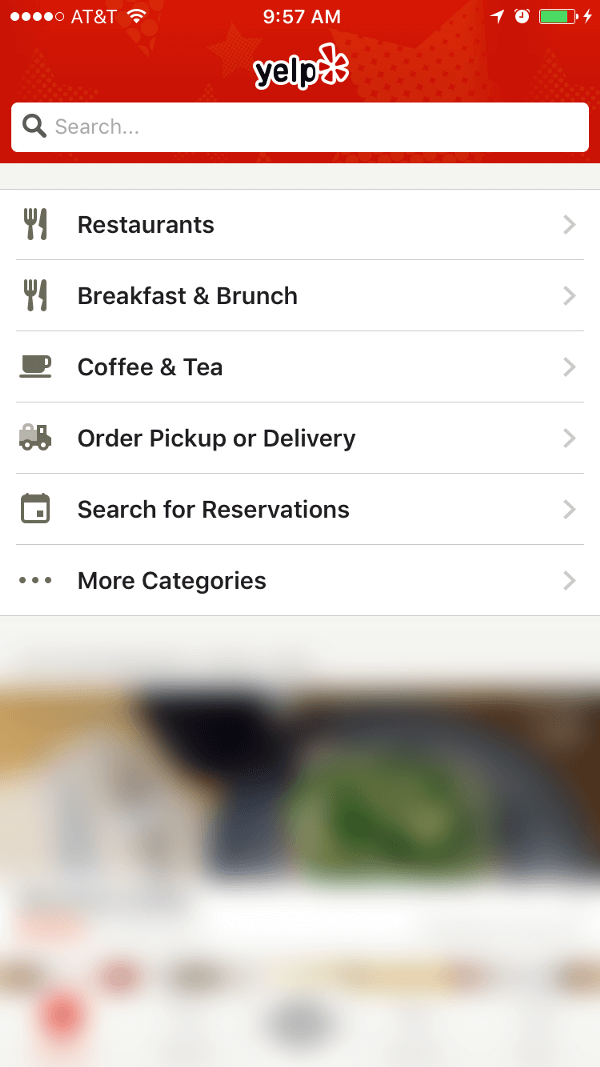

The tab bar pattern is inherited from desktop design. It usually contains relatively few destinations, and those destinations are of similar importance and require direct access from anywhere in the app.

When To Use

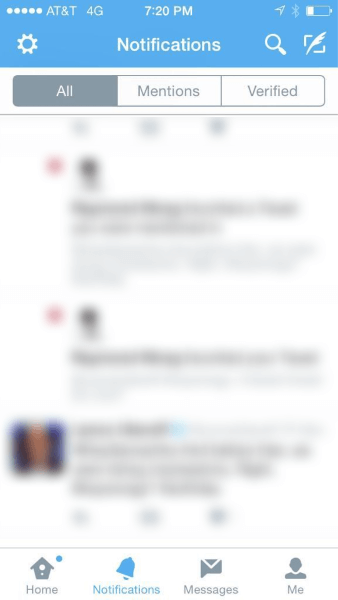

Tabbed navigation is a great solution for apps with relatively few top-level navigation options (up to five). The tab bar makes the main pieces of core functionality available with one tap, allowing rapid switching between features.

Pros

Cons

Tips

- Make touch targets big enough to be easily tapped or clicked. To calculate the width of each bottom navigation action, divide the width of the view by the number of actions. Alternatively, make all bottom navigation actions the width of the largest action.

Most users can comfortably and reliably hit a 10 × 10-millimeter touch target. (Image: UXmag) - Order the navigation options. Users expect to see a certain order in the tab bar. The first tab item has to be the home screen of the app, and the order of tabs should reflect their priority or the logical order in the user flow. One of the tabs should always be active and visually highlighted.

- Test your icons for usability. As you can see in the example below, app designers sometimes hide functionality behind icons that are pretty hard to recognize. To prevent this from happening, test your icons with the five-second rule: If it takes you more than five seconds to think of an appropriate icon for something, then it is unlikely that an icon can effectively communicate that meaning.

Bloom.fm app has a tab bar full of abstract icons. - If an icon fails the five-second rule (i.e. isn’t self-evident), it needs a text label. It’s pretty rare in the offline world that we rely on iconography alone to represent ideas — and for good reason. Due to the absence of a standard usage for most icons, text labels are necessary to communicate meaning and reduce ambiguity. Users should understand what exactly will happen before they tap on an element.

Use text labels to provide short, meaningful definitions to bottom navigation icons. (View large version)

Priority+ Pattern

The “Priority+” pattern was coined by Michael Scharnagl to describe navigation that exposes what’s deemed to be the most important navigation elements and hides away less important items behind a “more” button.

When to Use

This pattern might be good solution for content-heavy apps and websites with a lot of different sections and pages (such as a news website or a large retailer’s store). The Guardian makes use of the priority+ pattern for its section navigation. Less important items are revealed when the user hits the “All” button.

Pros

- This pattern prioritizes navigation options. It surfaces the most frequently accessed navigation options.

- It makes use of available screen space. As space increases, the number of exposed navigation options increases as well, which can result in better visibility and more engagement.

- This menu is very adaptive. You can scale it quite nicely across screen sizes without having to transform the pattern.

Cons

- It might hide some important navigation options. The priority+ pattern requires designers to assume the relative importance of navigation items. Be aware that the items you prioritize to be visible might not be the same ones users are looking for most.

Floating Action Button

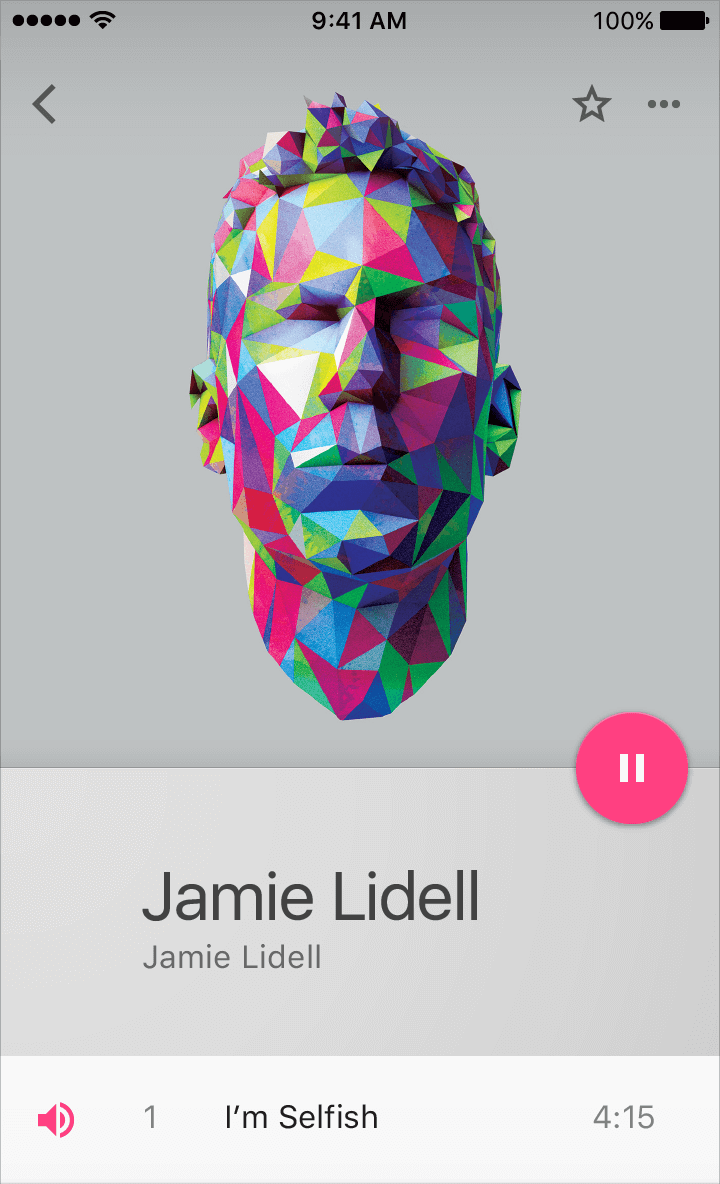

Shaped like a circled icon floating above the UI, the floating action button changes color upon focus and lifts upon selection. It’s well known by all Android users and is a distinct element of material design. Floating above the interface of an app, it promotes user action, says Google.

When to Use

The design of the floating action button hinges on the premise that users will perform a certain action most of the time. You can make this “hero” action even more heroic by reinforcing the sense that it is a core use case of your app. For example, a music app might have a floating action button that represents “play.”

The button is a natural cue to users for what to do next. In user research, Google found that users understand it as a wayfinding tool. When faced with an unfamiliar screen, as many users are regularly (like when running an app for the first time), they will use the floating action button to navigate. Thus, it is a way to prioritize the most important action you want users to take.

Pros

- It’s a signpost of what’s important. It’s a good way to prioritize the most important action you want users to take.

- It takes up little screen space. Compared to the tab bar, it doesn’t take up an entire row.

- A visually pleasing UI element such as this might not improve usability. However, emotion is a factor in user experience. If a user is pleased to use an app because they find it visually attractive, then that would create positive UX effects.

- It also improves effectiveness. A study by Steve Jones demonstrates that a floating action button slightly impairs usability when users first interact with the button. However, once users have successfully completed a task using the element, they are able to use it more efficiently than a traditional action button.

Cons

- A floating action button can distract users from content. It is designed to stand out — it is colorful, raised and grid-breaking. Its design is meant to draw the user's attention. But sometimes its presence can distract the user from the main content.

A red button stands out from the background and focuses user attention. (Image: Paul van Oijen) (View large version) - It can block content. Take Google’s Gmail app for instance. In the example below, you can see that it blocks the “favorite” star, as well as the time stamp for the last row. Additional scrolling is needed whenever the user wants to see this information.

- It is also icon-only navigation. By design, the floating action button is a circle containing an icon. It’s an icon-only button, with no room for text labels. The problem is that icons are incredibly hard to understand because they’re so open to interpretation. Even a simple action icon like the pencil in the example below can mean different things in different apps.

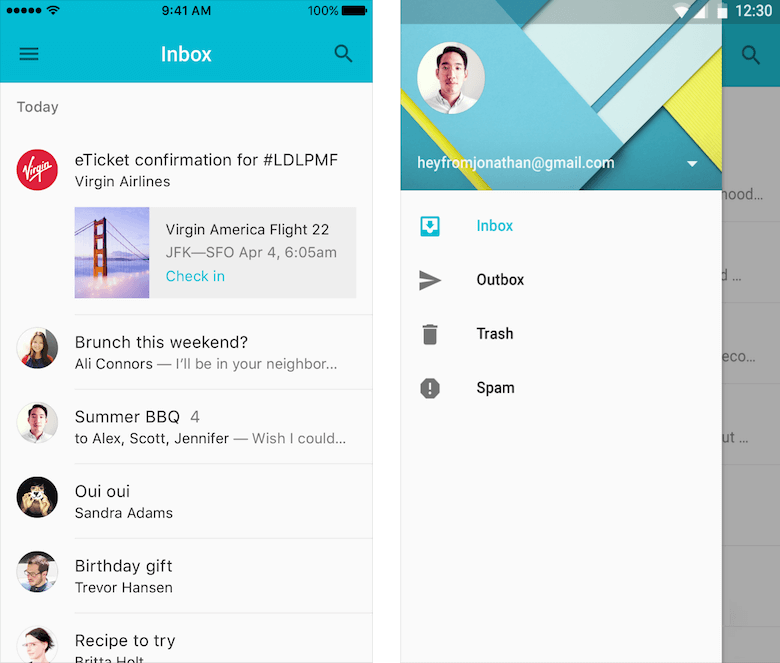

Same icon, different meanings: “Compose” in the Gmail and Inbox apps, but “Edit” in the Snapseed app. Here, context helps to explain the action. (View large version)

Tips

- Because it is so prominent and intrusive, use only one per screen.

Multiple floating action buttons should never appear on screen at one time because that would confuse the visual hierarchy. (View large version) - Not every screen should have one, simply because not every screen has an action of such importance.

- The floating action button is strongly associated with positive actions. Because it is full of character, it’s generally taken to be a positive action, like create, favorite, navigate, search and so on. Don’t use it for destructive actions, like delete.

(View large version) - The floating action button could be replaced with a sequence of more specific actions. This would help to surface a set that doesn’t really belong at the top but is still important. Apps such as Evernote simplify the controls by using a floating action button for the most important user actions.

- It can improve transitions between screens, too. The floating action button is not just a round button; it has some transformative properties that you can use to ease users from screen to screen. It can expand, morph and react.

(Image: Anish Chandran)

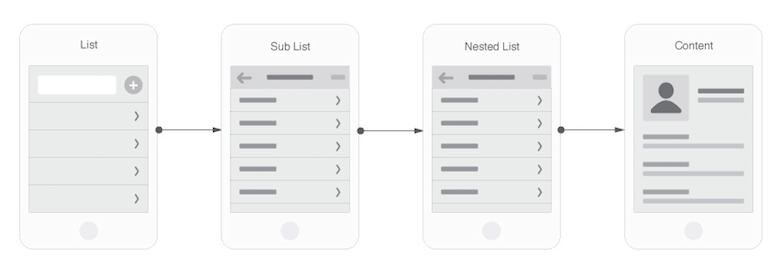

Full-Screen Navigation

While with other patterns mentioned in this article, you’d be struggling to minimize the space that the navigation systems take up, the full-screen pattern takes the exact opposite approach. This navigation approach usually devotes the home page exclusively to navigation. Users incrementally tap or swipe to reveal additional menu options as they scroll up and down.

When to Use

This pattern works well in task-based and direction-based websites and apps, especially when users tend to limit themselves to only one branch of the navigation hierarchy during a single session. Funnelling users from broad overview pages to detail pages helps them to home in on what they’re looking for and to focus on content within an individual section.

Pros

- The full-screen navigation pattern is best for achieving simplicity and coherence. You can organize large chunks of information in a coherent manner and reveal information without overwhelming the user; once the user makes their decision about where to go, then you can dedicate the entire screen space to content.

Cons

- Prime real estate will be wasted on chrome. You won’t be able to display any content except the navigation options.

Tips

- Use a hamburger menu to hide secondary functionality and keep the focus on the main experience.

(Image: Cookly via Dribbble)

Gesture-Based Navigation

29 June 2007 was a game changer. From the moment Apple launched the first fully touchscreen smartphone on the market, mobile devices have been dominated by touchscreen interaction.

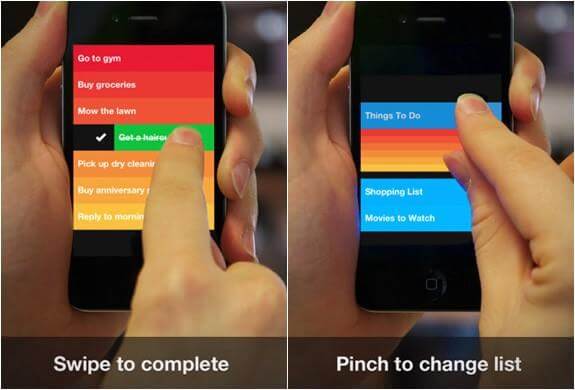

Gestures immediately became popular among designers, and many apps were designed around experimenting with gesture controls.

In today’s world, the success of a mobile app can largely depend on how well gestures are implemented in the user experience.

When to Use

This pattern is good when users want to explore the details of particular content easily and intuitively. Users will spend more time with content than they will with navigation menus. So, one of the reasons to use in-context gestures instead of a standard menu is that it’s more engaging. For example, as users view page content, they can tap on a card to learn more.

Pros

- It removes UI clutter. Building gestures into the heart of your design allows you to make your interfaces more minimal and to save screen space for valuable content.

- The UI is more natural. Luke Wroblewski talks about a study in which 40 people in 9 different countries were asked to create gestures for 28 different tasks, such as deleting, scrolling and zooming. He found that the gestures tend to be similar across culture and experience. For example, when prompted to “delete,” most people — regardless of nationality — tried dragging the object off screen.

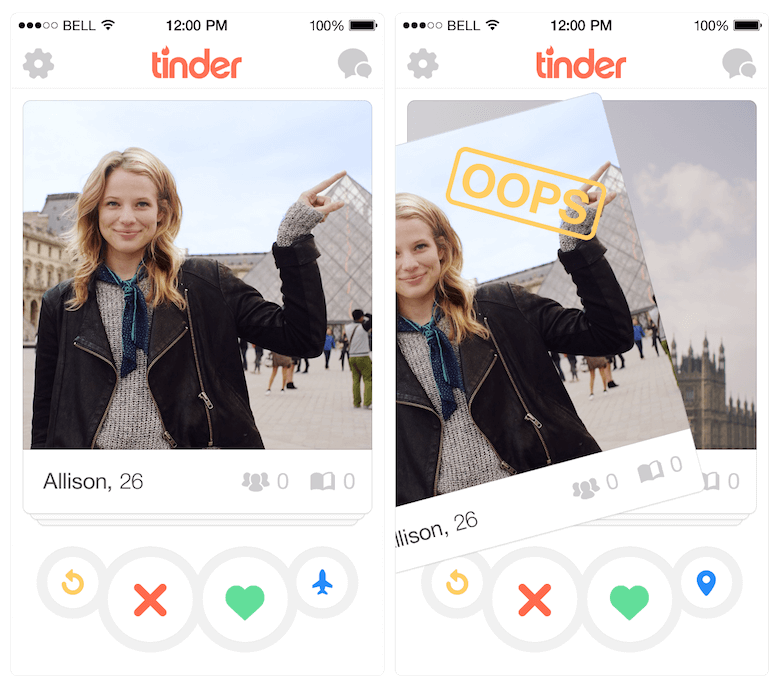

- Gestures can be a distinctive feature of a product. Tinder has massively popularized the concept of gesture-based navigation and basically made those swipes a product-defining gesture.

Cons

Tips

- Make sure you don’t have to teach people a whole new way to interact with an interface. Design a familiar experience. In order to design good gesture-based navigation, start by looking at the current state of gestures in the mobile world. For example, if you’re designing an email app, you could use a swipe instead of an email gesture, because there’s a strong possibility that the gesture would be familiar to many users:

- Educate in context to teach people how to interact with your interface. Avoid long static up-front tutorials. Instead, show only the information that is relevant to the user’s current activity.

Pudding Monsters uses an animated hand to present a new scenario to users.

3D Touch

3D Touch is a subtle touch mechanism that was first introduced in Apple’s iPhone 6s and 6s Plus. It allows for some new interactions, which Apple defines in two main categories:

- Quick actions

The iOS home screen isn’t just a grid of apps anymore, because 3D Touch allows users to perform actions specific to an app outside of the app, right from the home screen. Pressing firmly on an app icon presents a short list of quick actions: Jump right into taking a selfie from the Camera icon, or immediately navigate to your favorite contacts from the Messages app.

3D Touch quick-action shortcuts for the camera, messages and maps apps (View large version) - Peek and pop

3D Touch allows users to preview content and perform related actions within an app before deciding whether to view the full content. When users press firmly on a piece of content — such as a mail message in a list — 3D Touch opens a preview of what that content contains.

3D Touch immediately previews an email, which disappears when the user removes their finger. (Image: Gizmodo)

When to Use

Using 3D Touch, you can make the most frequent actions the most accessible. Think of 3D Touch like keyboard shortcuts on a desktop computer: They enable people to do repeated tasks more quickly. You can use 3D Touch to help users skip a few steps or to avoid unnecessary steps altogether.

However, just like keyboard shortcuts, essential features shouldn’t be exclusive to 3D Touch. Users must be able to operate your app normally without it.

Pros

- With its shortcut actions, 3D Touch has the potential to save users a lot of time by skipping several taps within an app.

- By simplifying an interface, 3D Touch enables quick, lightweight interaction. It gives designers and developers new opportunities to simplify their interfaces, while surfacing enhanced functionality for users.

Cons

- Users have to remember which apps have quick actions. 3D Touch still isn’t ubiquitous on iOS. Some apps have it, others don’t. Users sometimes expect 3D Touch shortcuts for apps that don’t have them.

Innovative Navigation Patterns

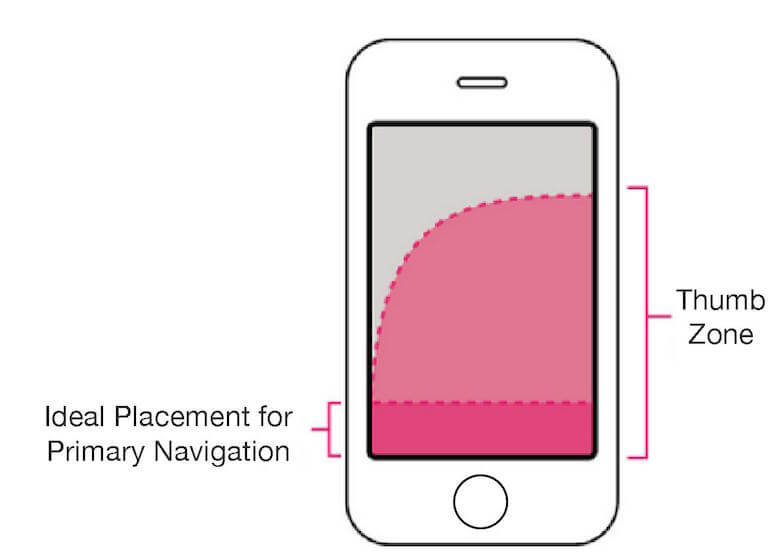

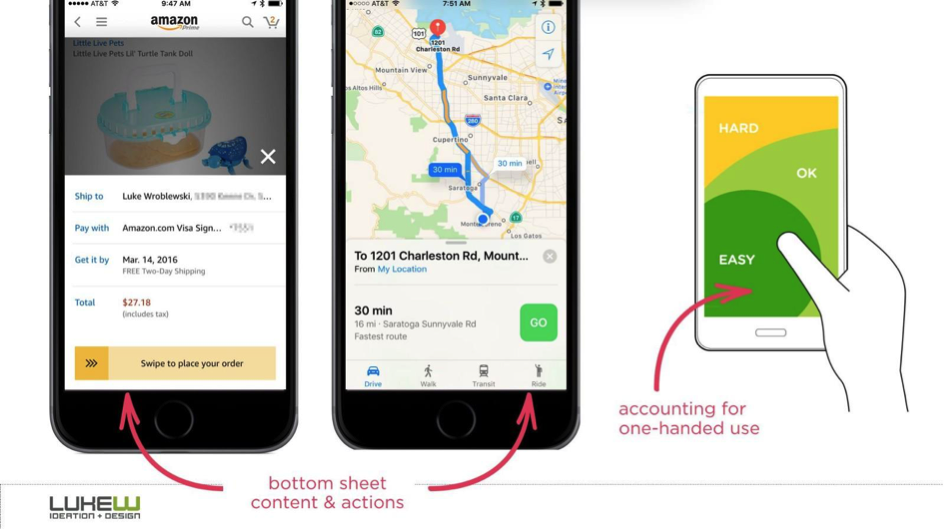

People are shifting to larger-screen phones. Large smartphones don’t surprise anyone anymore. But the bigger the display is, the less easily accessible most of the screen is, and the more necessary it is to adapt the design (and navigation, in particular) to improve the user experience.

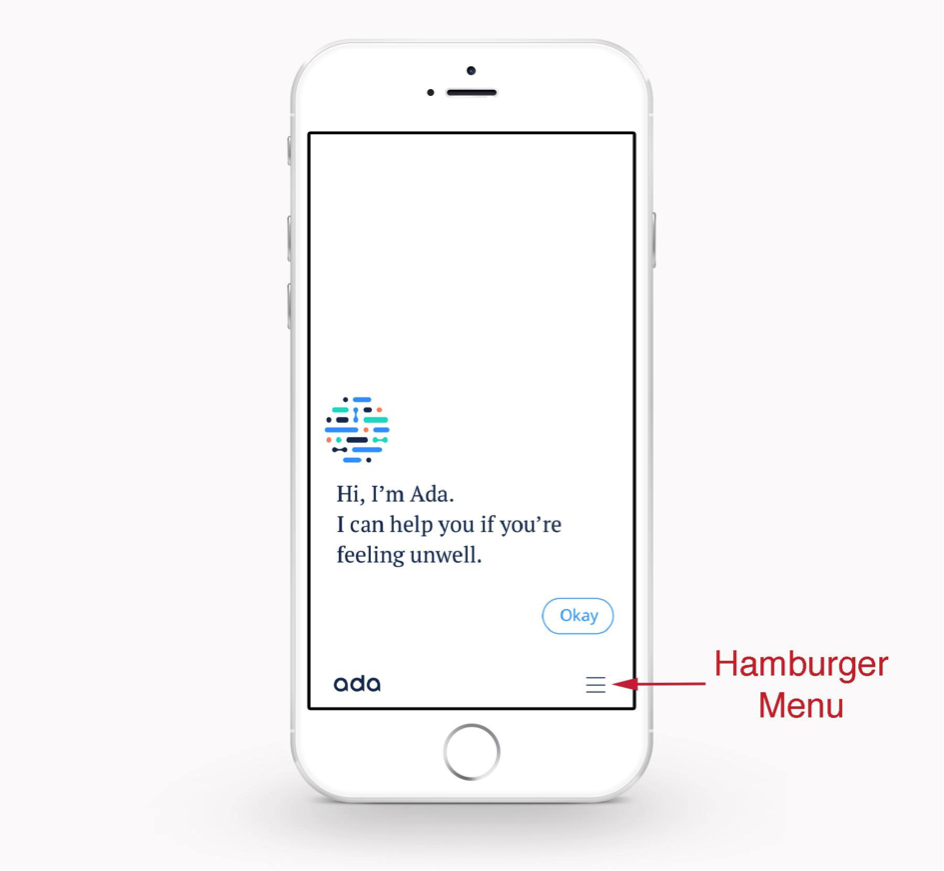

To solve this problem, designers are forced to look for new solutions to navigation. A couple of interesting innovative solutions can be found in the recently published article “Bottom Navigation Interface.” One solution can be found in a health app named Ada. This app’s interface layout is a mirror image of a basic interface with a hamburger menu: Everything that’s usually at the top is conveniently at the bottom, in the easy-to-access zone.

The second solution is a concept for a calling app that applies one-handed navigation principles. The method feels good for calling and messaging apps because users tend to use one hand for dialing and texting.

Conclusion

Helping users navigate should be a high priority for every app designer. Both new and returning users should be able to figure out how to move through your app with ease. The easier your product is for them to use, the more likely they’ll use it.

This article is part of the UX design series sponsored by Adobe. The newly introduced Adobe Experience Design CC (Beta) tool is made for a fast and fluid UX design process, as it lets you go from idea to prototype faster. Design, prototype and share — all in one app. You can check out more inspiring projects created with Adobe XD on Behance, and also visit the Adobe XD blog to stay updated and informed. Adobe XD is being updated with new features frequently, and since it’s in public Beta, you can download and test it for free.

(ms, vf, al, yk, il)

(ms, vf, al, yk, il)