The common wisdom for most companies that set out to build an app is to build a native Android or iOS app, as well as a supporting website. Although there are some good reasons for that, not enough people know about the major advantages of web apps. Web apps can replace all of the functions of native apps and websites at once. They are coming more and more to the fore these days, but still not enough people are familiar with them or adopting them.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- A Beginner’s Guide To Progressive Web Apps

- Building A First-Class App That Leverages Your Website

- Creating A Complete Web App In Foundation For Apps

Here, you will be able to find some do’s and dont’s on how to make a progressive web app, as well as resources for further research. I’ll also go into the various components and support issues surrounding web apps. Although not every browser is friendly to them, there are still some compelling reasons to learn more about this technology.

What Makes A Web App Progressive?

A progressive web app is an umbrella term for certain technologies that go together to produce an app-like experience on the web. For simplicity’s sake, I’ll refer to them simply as web apps from now on.

An ideal web app is a web page that has the best aspects of both the web and native apps. It should be fast and quick to interact with, fit the device’s viewport, remain usable offline and be able to have an icon on the home screen.

At the same time, it must not sacrifice the things that make the web great, such as the ability to link deep into the app and to use URLs to enable sharing of content. Like the web, it should work well across platforms and not focus solely on mobile. It should behave just as well on a desktop computer as in other form factors, lest we risk having another era of unresponsive m.example.com websites.

Progressive web apps are not new. Mobile browsers have had the ability to bookmark a website to your phone’s home screen since 2011 (2013 on Chrome Android), with meta tags in the head determining the appearance of the installed web page. The Financial Times has been using a web app for digital content delivery on mobile devices since 2012.

Moving to a web app enabled the Financial Times to use the same app to ship across platforms in a single distribution channel. Back when I was working for the Financial Times, with a single build we were able to support the following:

- iOS,

- Android (4.4+) Chrome,

- older Android (via a wrapper),

- Windows 8,

- BlackBerry,

- Firefox OS.

That truly achieves “build once, deploy anywhere.”

“But It’s Not In An App Store”

There are some good reasons why supplementing a native app with a website is still standard practice for most major companies. Among them are concerns about browser support and the fact that most users are acclimated to using native apps. I will address these issues in more detail later. Not least of these concerns is how the app will get exposure if it is not in an app store.

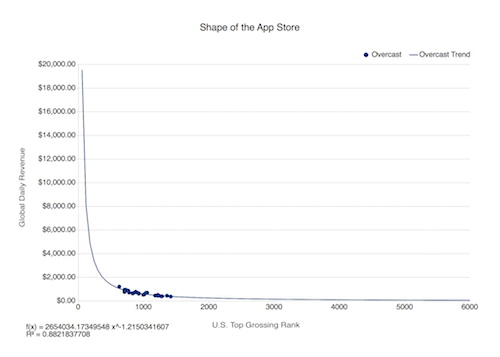

I would argue that being in an app store has no major advantage because it has been shown that if you are not in the top 0.1% of apps in the app store, you are not getting significant benefit from being there.

Users tend to find your apps by first finding your website. If your website is a web app, then they are already at their destination.

One of the strengths of a web app is that it enables you to improve engagement by reducing the number of clicks required to re-engage the user between landing on your website and engaging with your app.

By having the user “install” your web app by adding it to their home screen, they can continue engaging with your website. When they close down the web browser, the phone will show them where the web app is installed, bringing you back to their awareness.

Background And Current Climate

Modern web apps are based on a new technology called service workers. Service workers are programmable proxies that sit between the user’s tab and the wider Internet. They intercept and rewrite or fabricate network requests to allow very granular caching and offline support.

Since the origins of the web app in 2011, which enabled websites to be bookmarked to the home screen, a number of developments have taken place to lay more groundwork for the creation of progressive web apps.

Chrome 38 introduced the web app manifest, which is a JSON file that describes the configuration of your web app. This allowed us to remove the configuration from the head.

In Chrome 40 (December 2014), service workers started to roll out across Firefox and Chrome. Apple has so far chosen not to implement this feature in Safari as of the time of writing but has it “under consideration.” The service worker’s function is to simplify the process of bringing an app offline; it also lays the foundation for future app-like features, such as push notifications and background sync.

Apps that were built based on the new service workers and the web app manifest became known as progressive web apps.

A progressive web app is not the same as the spec. In fact, it started out as a definition of what a web app should be in the era of service workers, given the new technology being built into browsers. Specifically, Chrome uses this definition to trigger an install prompt in the browser when a number of conditions are met. The conditions are that the web app:

- has a service worker (requires HTTPS);

- has a web app manifest file (with at least minimal configuration and with

display: "standalone"); - has had two distinct visits.

In this case, “progressive” means that the more features the browser supports, the more app-like the experience can be.

The prompt to install the web app is currently shown under varying conditions across Opera, Chrome and the Samsung browser.

Apple has indicated interest in progressive web apps for iOS, but at the time of writing it still relies on meta tags for web app configuration and the application cache (AppCache) for offline use.

At What Point Does A Website Become A Web App?

We know what a website looks like and what an app looks like, but at what point does a website become a web app? There is no definitive metric as to what makes something a web app rather than a website.

Here we will go into some more detail about the characteristics of a web app.

A Progressive Web App Should Exhibit Certain App-Like Properties…

- Responsive

Perfectly filling the screen, these websites are primarily aimed at phones and tablets and must respond to the plethora of screen sizes. They should also just work as desktop websites. Responsive design has been a major part of website building for many years now. Smashing Magazine has some great articles on it. - Offline-first

The app must be capable of starting offline and still display useful information. - Touch-capable

The interface should be designed for touch, with gesture interaction. User interaction must feel responsive and snappy, with no delay between a touch and a response. - App meta data

The app should provide meta data to tell the browser how it should look when installed, so that you get a nice high-resolution icon on the home screen and a splash screen on some platforms. - Push notifications

The app is able to receive notifications when the app is not running (if applicable).

… But Should Maintain Certain Web-Like Properties

- Progressive

The app’s ability to be installed is a progressive enhancement. It is vital that the app still work as a normal website, especially on platforms that do not yet support installation or service workers. - HTTPS on the open web

The app should not be locked to any browser or app store. It should be able to be deep linked to and should provide methods for sharing the current URL.

Taking Your Website Offline

Taking your website offline brings some major advantages.

First, it will still work when the user is on a flaky network connection.

In addition, the time from opening the app to using the app is greatly reduced if the app does not rely on the network. This gives the user a great experience. A carefully optimized web app can start faster than a native one if the browser has been used recently.

There are two methods to getting a website to work offline:

- Old and busted method

Support for starting your website offline has been around for years in the form of AppCache. AppCache has some serious flaws, though, and has even been deprecated from the specification. It is difficult to work with and, if misconfigured, could permanently break your website. Still, it is the only way to do offline on iOS, at least until Apple makes a move to support service workers. - New hotness

Also effective are service workers, which are currently supported in Chrome, Firefox and Opera and coming very soon to Edge. Apple’s WebKit team has it marked “under consideration.”

Service workers are like other web workers in that they run in a separate thread, but they are not tied to any specific tab. They are assigned a URL scope when they are created, and they can intercept and rewrite any requests in this scope. If your service worker sits at http://example.com/my-site/sw.js, it will be able to intercept any requests made to /my-site/ or lower but cannot be made to intercept requests to the root http://example.com/.

Because they are not tied to any tab, they can be brought to life in the background to handle push notifications or background sync. Not least, it is impossible to permanently break your website with them because they will automatically update when a new service worker script is detected.

A good guideline is that, if you are building a new website from scratch, start off with a service worker. However, if your website already works offline with AppCache, then you can use the tool sw-appcache-behavior to generate a service worker from this, because we may soon reach the point when some browsers will only accept service workers and some will only accept AppCache.

Because AppCache is being deprecated, I will not discuss it further in this article.

Setting Up A Service Worker

(Also, see “Setting Up a Service Worker” for more detailed instructions.)

Because a service worker is a special type of shared web worker, it runs in a separate thread to your main page. This means that it is shared by all web pages on the same path as the service worker. For example, a service worker located at /my-page/sw.js would be able to affect /my-page/index.html and my-page/images/header.jpg, but not /index.html.

Service workers are able to intercept and rewrite or spoof all network requests made on the page, including those made to data:// URLs!

This power enables it to provide cached responses to get pages to work when there is no data connection. Still, it is flexible enough to allow for many possible use cases.

It is only allowed in secure contexts (i.e. HTTPS) because it is so powerful. This prevents third parties from permanently overriding your website using an injected service worker from an infected or malicious Wi-Fi access point.

Setting up HTTPS nowadays might seem daunting and expensive, but actually it has never been easier or cheaper. Let’s Encrypt provides free SSL certificates and scripts for you to automatically configure your server. In case you host on GitHub, GitHub Pages are automatically served over HTTPS. Tumblr pages can be configured to run on HTTPS, too. CloudFlare can proxy requests to upgrade to HTTPS.

Offlining usually involves picking certain caching methods for different parts of your website to allow them to be served faster or when there is no Internet connection. I will discuss various caching methods below.

I use Service Worker Toolbox to abstract away complex caching logic. This library can be set to handle the routing by providing four preconfigured routes, which can be configured in a clean fashion. It can be imported into your service worker.

Use Case 1: Precaching

Precaching pulls down requests before your website works out that they are needed. This can greatly decrease first paint time because your website doesn’t need to parse /site.css before it starts downloading your website’s logo, /images/logo.png.

toolbox.precache(['/index.html', '/site.css', '/images/logo.png']);

Use Case 2: Offline

Allowing users to revisit your website when they are offline in the simplest case means falling back to the cache if the device is offline. Setting a timeout here is important because a flaky network, misconfigured router or captive portal could leave the user waiting indefinitely.

toolbox.router.default = toolbox.networkFirst;

toolbox.options.networkTimeoutSeconds = 5;

In reality, we can actually be a little smarter because the majority of your assets will not change over time. We probably just want to get the content as soon as possible, whether from the cache or the network. The following line tells Service Worker Toolbox that all requests to the images’ paths should come from the cache if they are available there.

toolbox.router.all('/images/*', toolbox.fastest);

In this case, when the user is authenticating, it is important that we not just return a cached response; we should state that requests made to /auth/ should be network-only.

toolbox.router.post('/auth/*', toolbox.networkOnly);

Here are some good practices for offlining:

- Initial static assets should be precached. This downloads them and caches them when the service worker is installed. This means that they do not need to be loaded from the server when they are eventually required.

- By default, requests should ideally be freshly sourced from the network but fall back to the cache so that they are available offline.

- A relatively short network timeout means that requests will be able to return cached data on a network connection that says it has a data connection but no responses are being returned.

- Infrequently updated assets, such as images, should be dispatched from the cache first, then the browser would also try to update them. If

toolbox.cacheOnlyis used, then it could also save the user’s data.

Note: The browser cache and the Cache API are different animals. The Cache API has been bypassed in the case of network-first or network-only. The request might still hit the browser’s cache because the caching headers in the request say it is still valid. This could result in the problem of the user receiving a mixture of cached and fresh data. Jake Archibald has some good suggestions for avoiding this issue.

Debugging Your Service Worker

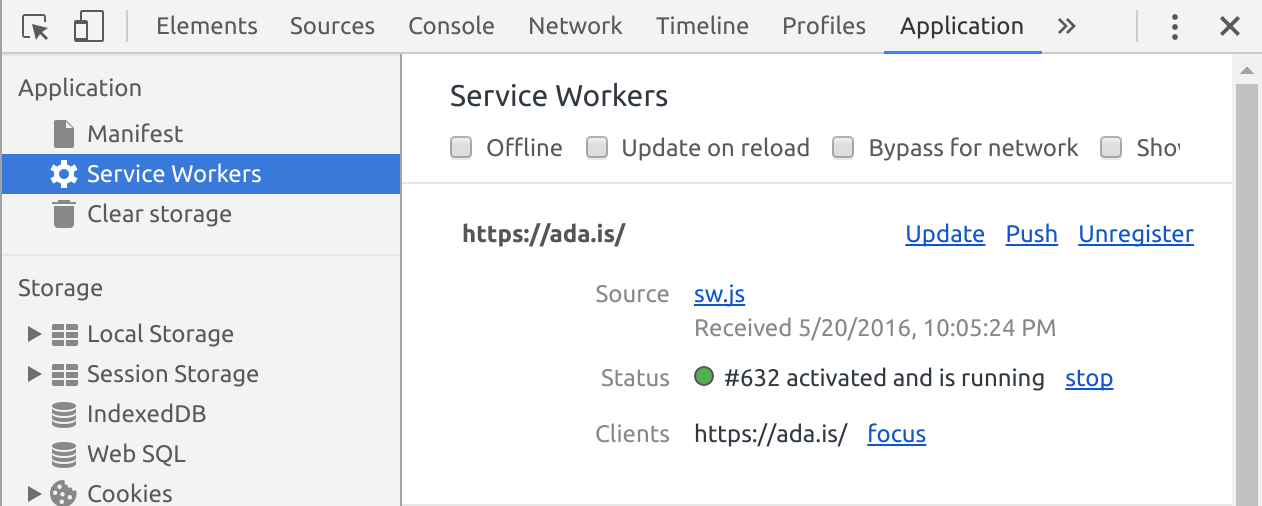

If you are in Chrome or Opera, go to chrome://serviceworker-internals. This will allow you to inspect and pause and uninstall your service worker script.

In recent versions of Chrome and Opera, you can get detailed views and debugging tools through the “Application” tab in the inspector.

Interaction And Animation Performance

People have come to expect that the web does not have the smoothly animated interfaces that native apps do. However, the same standard is not acceptable for web apps. Web apps must animate smoothly, lest our users feel we are delivering a degraded, second-class experience. We have three goals to make it feel fast:

- When the user does something, the app must also do something within 100 milliseconds; otherwise, the user will notice a lag. This counts for taps, clicks, drags and scrolls.

- Each frame must render at a consistent 60 frames per second (16 milliseconds per frame). Even a few slow frames will be obvious.

- It must be fast on a three-year-old budget phone running on a poor network, not only your shiny development machine.

- It must start quickly. Long have we been focused on maintaining user engagement by getting our websites to be visible and usable in under 1 to 2 seconds. When it comes to web apps, start-up time is as important as ever. If all of an app’s content is cached and the browser is still in the device’s memory, a web app can start faster than a native app. One mistake made by native app and website developers alike is requiring networked content in order for the product to work.

- The web app must be small to download and update: 10 MB from an app store don’t feel like much, but 10 uncached MB downloaded every time is very much impossible to manage for a lot of mobile users.

Off the bat, the most essential item is this, in the head of the document:

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width">

This line ensures that there is no 300-millisecond tap delay on phone browsers that are Chromium-based or Firefox, but it still allows the user to zoom in by pinching (great for accessibility).

Since iOS 8 came out, clicks are fast by default but might seem slow if the tap is fast, according to certain heuristics. If this is an issue for you, I recommend using FastClick to remove the delay.

There is also the issue of animation performance. You’ll probably want a lot of pretty elements animating in and out, elements that can be dragged by the user, and other lovely interactions.

Web performance can be discussed in great detail and is a subject close to my heart, but I won’t go into much detail here. I will touch on what I do to ensure that my interactions and animations are crisp and smooth.

Dig around or ask around your friends or family for an old smartphone. I usually borrow my partner’s Nexus 4.

Plug the phone into your computer, and go to chrome://inspect/#devices. This will open an inspection window, which you can use to inspect the web pages running on the phone. You can use profiling and view the timeline to find sources of poor performance and then optimize them based on a real baseline device.

Animating certain CSS properties is one of the biggest causes of jittery animation, known as jank. CSS Triggers is a great resource for determining which properties can be safely animated without causing the browser to repaint or re-lay out the whole page.

If writing performant animations is a daunting task for you, many libraries out there will handle the job. A favorite of mine is GreenSock, which can handle touch interactions very well, such as dragging items, and which can do very fancy animation and tweening.

Push Notifications

Push notifications are a great way to re-engage with users. By prompting the user, you bring your app to the forefront of their mind. They could finish off an unfinished transaction or receive alerts about relevant new content.

Make sure your push notifications are relevant to the user for events happening at that moment. Don’t waste their time on things that can be done later. What you are notifying them about should require their action (replying to someone or going to an event). Also, don’t push a notification if your web app is visible or in focus.

When interacted with, a notification should take the user to a page that works offline. Notifications can hang around unread; they might be interacted with when the user has no network connection. The user will get frustrated if your push notification refuses to work after they have tried to interact with it.

The very best experience for push notifications frees the user from having to open your web app at all! “You have a new message” is useless and as annoying as a clickbait headline. Display the message and the sender.

Action buttons in the notification can provide interaction prompts that do not necessarily open the browser (“Like this post,” “Reply with yes,” “Reply with no,” “Remind me later”). These serve the user on their terms, keeps them engaged and minimizes their investment of time.

If you spam the user with regular or irrelevant notifications, they might disable notifications for your app in the browser. After that, it will be almost impossible to re-engage them, and you won’t be able to easily prompt them for permission again!

To avoid this, make the route to your app’s “disable notification” button clear and easy. Once you have addressed any issues frustrating users, you can try to re-engage.

The Push Notification API requires a service worker. Because it is possible to receive push notifications when no browser tab is open, the service worker will handle the notification request in a background thread. It can perform async operations, such as making a fetch request to your API before displaying the notification to the user.

To create a push notification, make a request to an endpoint provided by the browser manufacturer. For Chromium-based browsers (Opera, Samsung and Chrome), this would is Firebase Cloud Messaging. These browsers also behave a little off-spec as well.

One can find the details of this by requesting push-notification permission:

serviceWorkerRegistration

.pushManager

.subscribe({

// Required parameter as receiving updates

// but not displaying a message is not supported everywhere.

userVisibleOnly: true

})

.then(function(subscription) {

return sendSubscriptionToServer(subscription);

})

The subscription is an object that looks like this:

{

"endpoint": "http://example.com/some/uuid"

}

In the example above, the uuid uniquely identifies the browser currently being used.

Note: Chromium-based browsers behave a little differently. You’ll need a Firebase app ID, which needs to be entered in your web app’s manifest file (for example, "gcm_sender_id": "90157766285").

Also, the endpoint will not work in the format it is given. Your server needs to mangle it slightly to get it to work. It needs to be a POST request, with your API key in the head and the uuid in the body.

When sending a push notification, it is possible to send data in the body of the push notification itself. This is complex and involves encrypting the contents in the API request. The web-push package for Node.js can handle this, but I don’t prefer it.

It is possible to perform async requests once the notification has been received, so I prefer to send a minimal notification, known as a “tickle,” to the client, and then the service worker will make a fetch request to my API to pull any recent updates.

Note: The service worker can be closed by the browser at any point. The event.waitUntil function in the push event tells the service worker not to close until the event is finished.

self.addEventListener('push', function(event) {

event.waitUntil(

// Makes API request, returns Promise

getMessageDetails()

.then(function (details) {

self.registration.showNotification( details.title, {

body: details.message,

icon: '/my-app-logo-192x192.png'

})

})

);

});

You can listen for a click or press interaction on the notification events, too. Use these to decide how to respond. You could open a new browser tab, focus an existing tab or make an API request. You can also choose whether to close the notification or keep it open. Use this functionality with actions on the notification to build great functionality into the notification itself. This will make for a great experience, because the user will not be required to open your app each time.

Don’t Ignore The Strengths Of The Web

The final and most important point is that, in our rush for an app-like experience, we should not forget to stay web-like in one very important aspect: URLs.

Installed web apps often hide the browser shell. There is no address bar for the user to share the current URL, and the user can’t save the current page for later.

URLs have a unique web advantage: You can get people to use your app by clicking, rather than by describing how to navigate it. All the same, it is very easy to forget to expose this to users. You could write the best app in the world, but if no one can share it, you will have done yourself a major disservice.

It comes down to this: Provide ways to share your app via either sharing buttons or a button to expose the URL.

What About Browsers That Do Not Support Progressive Web Apps?

Check out Is ServiceWorker ready? for the current status of support for service workers across browsers.

You may have noticed throughout all of this that I have mentioned Chrome, Firefox and Edge but left out Safari. Apple introduced web apps to the world and has shown interest in progressive web apps, but it still does not support service workers or the web app manifest. What can you do?

It is possible to make an offline website for Safari with AppCache, but doing so is both difficult and fraught with weird edge cases that can break the page or keep it permanently out of date after first load.

Instead, build a great web app experience. Your work will not have been wasted because the experience will still be great in Safari, which is a very good browser. When service workers do come to Safari, you will be ready to take advantage of them.

Finally, we can look forward to a lot of exciting developments in the world of web apps, with increasing support for the technologies behind them and new features coming to the web platform, such as the Web Bluetooth API for interacting with hardware, WebVR for virtual reality, and WebGL 2 for high-speed gaming. Now is a great time to explore the possibilities of web apps and to take part in shaping the future of the web.

Links

Other Writing on Progressive Web Apps

- “Yet Another Blog About the State and Future of Progressive Web App,” Ada Rose Edwards

Links Referred to in Article

- “The Shape of the App Store,” Charles Perry

- Service Worker Helpers, Google, GitHub

- Service Worker Toolbox, Google, GitHub

- “The 300 Millisecond Click Delay and iOS 8,” TJ VanToll

- “Caching best Practices and max-age Gotchas,” Jake Archibald

(vf, yk, il, al)

(vf, yk, il, al)

Editor’s Note: We kindly thank Christian Heilmann for his kind technical and editorial support — this article wouldn’t be possible without him.