Here’s a challenge for you: what about building a 3D game over the weekend? Babylon.js is a JavaScript framework for building 3D games with HTML5, WebGL and Web Audio, built by yours truly and the Babylon.js team. To celebrate the new version 2.3 of the library, we decided to build a new demo named “Sponza” to highlight what can be done with the WebGL engine and HTML5 when it comes to building great games nowadays.

The idea was to create a consistent, similar, if not identical, experience on all WebGL supported platforms and to try to reach native apps’ features. In this article, I’ll explain how it all works together, along with the various challenges we’ve faced and the lessons we’ve learned while building it.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Building Shaders With Babylon.js

- Using The Gamepad API In Web Games

- Introduction To Polygonal Modeling And Three.js

- How To Create A Responsive 8-Bit Drum Machine

To achieve this goal, Sponza uses a number of HTML5 features like WebGL, Web Audio, as well as Pointer Events (widely supported now thanks to jQuery PEP polyfill), Gamepad API, IndexedDB, HTML5 AppCache, CSS3 transition/animation, flexbox and Fullscreen API. You can test the Sponza demo on your desktop, mobile or Xbox One.

Discovering The Demo

First, you’ll start on an auto-animated sequence giving the credits to whoever has built the scene. Most of the team’s members come from the demo scene. You’ll discover that this is an important part of the 3D developers’ culture. On my side, I was on Atari while David Catuhe was on Amiga which is still a regular source of conflicts between us, believe it or not. I was coding a bit but mainly composing the music in my demo group. I was a huge fan of Future Crew and more specifically of Purple Motion, my favorite demo scene composer of all time. But let’s not deviate from the topic.

For Sponza, here are the contributors:

- Michel Rousseau aka “Mitch” has done remarkable visuals animations & rendering optimizations acting as the 3D artist. It took the Sponza model provided freely by Crytek on their website and used the 3DS Max exporter to generate what you see.

- David Catuhe aka “deltakosh” and I have done the core part of the Babylon.js engine and also all the code for the demo (custom loader, special effects for the demo mode using fade to black post-processes etc.) as well as a new type of camera named “UniversalCamera” handling all type of inputs in a generic way.

- I’ve composed the music using Renoise and the EastWest Symphonic Orchestra sound bank. If you’re interested, I’ve already shared my workflow and process in the article on Composing the music for the World Monger Windows 8 game using the Renoise tracker & East West VST Plug-ins

- Julien Moreau-Mathis helped us by building a new tool to help 3D artists finalize the job between the modelling tools (3DS Max, Blender) and the final result. For instance, Michel used it to test and tune various animated cameras and to inject particles into the scene.

If you wait until the end of the automatic sequence up to the “epic finish”, you’ll be automatically switched to the interactive mode. If you’d like to by-pass the demo mode, simply click on the camera icon or press A on your gamepad.

In the interactive mode, if you’re on a Mac or PC, you’ll be able to move inside the scene using keyboard/mouse like a FPS game. If you’re on a smartphone, you’ll be able to move using a single touch (and 2 to rotate camera). Finally, on an Xbox One, you can use the gamepad (or desktop if you’re plugging a gamepad into it). Fun fact: on a Windows touch PC, you can potentially use 3 types of input at the same time.

The atmosphere is different in the interactive mode. You’ve got three storm audio sources randomly positioned in the 3D environment, wind blows and fire cracks on each corner. On supported browsers (Chrome, Firefox, Opera and Safari), you can even switch between the normal speaker mode and the headphone mode by clicking on the dedicated icon. It will then use the binaural audio rendering of Web Audio for a more realistic audio simulation — if you’re listening via headphones.

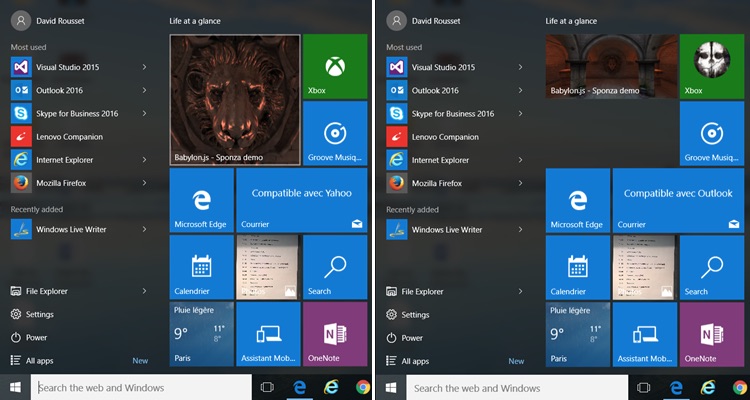

To have a complete app-like experience, we’ve generated icons and tiles for all platforms. This means, for instance, that on Windows 8⁄10 you can pin the web app into the “Start” menu. We even have multiple sizes available:

Offline first!

Once the demo has been completely loaded, you can switch your phone to airplane mode to cut connectivity and click on the Sponza icon. The web app will still provide the complete experience with WebGL rendering, 3D web audio and touch support. Switch it to full screen and you literally won’t be able to feel the difference between the demo and a native app experience.

We’re using IndexedDB layer available natively inside Babylon.js for that. The scene (JSON format) and the resources (JPG/PNG textures as well as MP3 for the music and sounds) are stored in IDB. The IDB layer coupled with HTML5 application cache is then providing the offline experience. To learn more about this part and how to configure your game to obtain similar results, you can read the article on Using IndexedDB to handle your 3D WebGL assets: sharing feedbacks & tips of Babylon.JS and Caching Resources in IndexedDB in Babylon.js

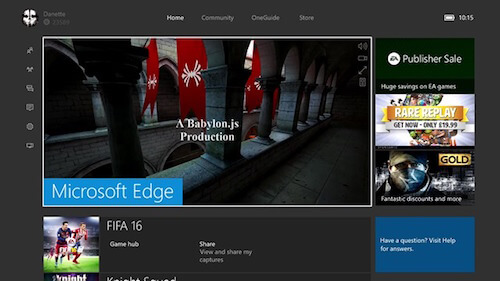

Xbox One enjoys the show

Last but not least, the very same demo works flawlessly in MS Edge on your Xbox One:

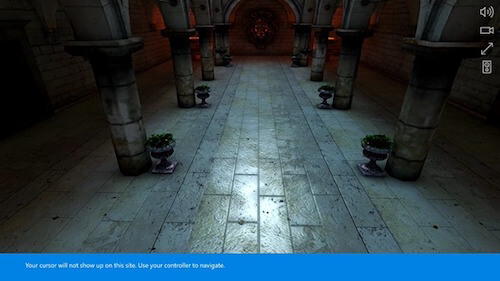

Press A to switch to interactive mode. The Xbox One will notify you that you can now move using your gamepad inside the 3D scene:

So, let’s briefly recap.

The very same code base works across Mac, Linux, Windows on MS Edge, Chrome, Firefox, Opera and Safari, on iPhone/iPad, on Android devices with Chrome or Firefox, Firefox OS and on Xbox One! Isn’t that cool? Being able to target so many devices with a fully-fledged native-alike experience directly from your web server?

I’ve already shared my excitement about the potential of the technology in a previous article on The web: the next game frontier?

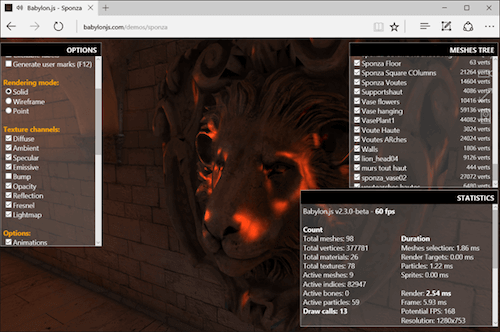

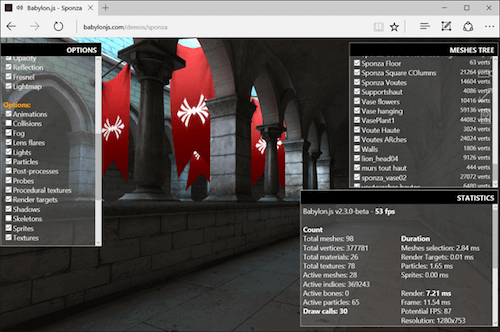

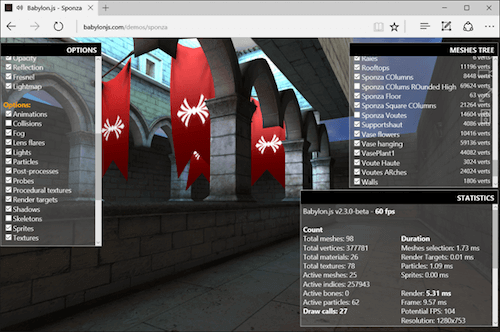

Hack The Scene With The Debug Layer

If you’d like to understand how Michel is mastering the magic of 3D modeling, you can hack the scene using the Babylon.js Debug Layer tool. To enable it on a machine with a keyboard, press CMD/CTRL + SHIFT + D and if you’re using a gamepad on PC or Xbox, press Y. Please note that displaying the debug layer costs a bit of performance due to the composition job the rendering engine needs to do. So the FPS displayed are a bit less important than the real FPS you’ve got without the debug layer displayed.

Let’s test it on a PC, for instance.

Move near the lion’s head and cut the bump channel from our shader’s pipeline:

You should see that the head is now less realistic. Play with the other channel to check what’s going on.

You can also cut the dynamic lightning engine or disable the collisions engine to fly or move through the walls. For instance, disable the “collisions” checkbox and fly to the first floor. Put the camera in front of the red flags. You can see them slightly moving. Michel has used the bones/skeletons support of Babylon.js to move them. Now, disable the “skeletons” option and they should stop moving:

At last, you can display the meshes tree on the top right corner. You can enable or disable them to completely break the work done by Michel:

Removing the geometries, the shader’s channels or some options of the engine can help you troubleshooting performances on a specific device to see what is currently costing too much. You can also check if you’re CPU-limited or GPU-limited, although most of the time, you’ll be CPU-limited in WebGL due to the mono-threading nature of JavaScript. Finally, the tool is also very useful to help you learn how a scene has been built by the 3D artist.

By the way, it works pretty well on Xbox One, too:

Challenges

Along the way, we faced a number of issues and challenges to build the demo. Let’s look into some of them in detail.

WebGL performance and cross-platform compatibility

The programming side was probably the easiest one to tackle as it’s completely handled by the Babylon.js engine itself. We’re using a custom shader’s architecture that adapts itself to the platform by trying to find the best shader available for the current browser/GPU using various fallbacks. The idea is to lower the quality and complexity of the rendering engine until we manage to display something meaningful on screen.

Babylon.js is mainly based on WebGL 1.0 to guarantee that the 3D experiences built on top of it will run pretty much everywhere. It has been built with the web philosophy in mind, so we’re progressively enhance on the shader compilation process. This is completely transparent for the 3D artist who doesn’t want to deal with these complexities most of the time.

Still, the 3D artist has a very important role in performance optimization. She has to know the platform she’s targeting, supported features and limitations. You can’t take assets coming from AAA games made for high-end GPUs and DirectX 12 and just integrate them into a game running on a WebGL engine. I’d argue that targeting WebGL today is quite similar to the work you’ll have to do to optimize for experiences on mobile devices, with a dash of extra JavaScript that has to be highly mono-threaded.

Mitch is extremely good at just that: optimizing the textures, pre-calculating the lightning to bake it into the textures, reducing the number of draw calls as much as possible, etc. He has years of experience behind him and saw the various generations of 3D hardware and engines (from PowerVR/3DFX to today’s GPUs) which really helped to make the demo happen.

He already shared a bit of those basics in his articles on Real Time 3D: making a demo for WebGL Purposes–Basics and already proved several times that you can create quite fascinating visual experience on the web with high performance on small integrated GPUs, e.g. in Mansion, Hill Valley or Espilit demo scenes. If you are interested, take the time to watch his talk on NGF2014 – Create 3D assets for the mobile world & the web, the point of view of a 3D designer where he shared his experience and how he managed to optimize the Hill Valley scene from less than 1 fps to 60 fps.

The initial goal for Sponza was to build two scenes. One for the desktop and one for mobile with less complexity, smaller textures and simpler meshes and geometries. But during our tests, we finally discovered that the desktop version was also running pretty fine on mobile as it can run up to 60fps on an iPhone 6s or an Android OnePlus 2. We then decided not to continue working on the simpler mobile version.

But again, it probably would have been better to have a clean mobile-first approach on Sponza to reach 30fps+ on many mobile device, and then enhance the scene for high-end mobile and desktop. Still, most of the feedback we’ve received so far on Twitter seems to indicate that the final result works very well on most devices. Admittedly, Sponza has been optimized on an HD4000 GPU (Intel Core i5 integrated) which is more or less equivalent to actual high-end mobiles’ GPUs.

We were quite happy with the performance we managed to achieve. Sponza is using our shader with ambient, diffuse, bump, specular and reflection enabled. We have some particles to simulate small fires on each corner, animated bones for the red flags, 3D positioned sounds and collisions when you’re moving using the interactive mode.

Technically speaking, we have 98 meshes used in the scene, generating up to 377781 vertices, 16 actives bones, 60+ particles that could generate up to 36 draw calls. What have we learned? One thing for sure: having a fewer draw calls is the key to optimal performance, even more so on the web.

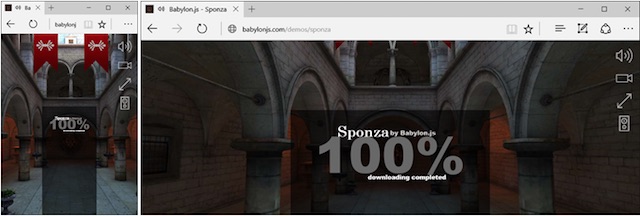

The loader

For Sponza, we wanted to create a new loader, different than the default one we’re using on the BabylonJS website, to have a clean and polished web app. I’ve then asked Michel to suggest something new.

He first sent the following screen over to me:

Indeed, the screen looks very nice when you first have a look to it. But then you might start wondering on how you’ll make it work on all devices, in a truly responsive way? Let’s figure it out.

Let’s talk about the background first. The blurry effect created by Michel was nice but wasn’t working well across all window sizes and resolutions generating some moiré. I’ve then replaced it with a “classical” screenshot of the scene. However, I wanted the background to completely fill the screen without black bars and without stretching the image to break the ratio.

The solution mainly comes from CSS background-size: cover + centering the image on X and Y axes. As a result, we then have the experience that I was looking to, whatever the screen ratio is used:

The other parts are using the good ol’ percentage-based CSS positioning. Okay, with that sorted, how do we handle the typography — the font-size should be based on the size of the viewport. Obviously, we can use viewport units for that. vw and vh (where 1vw is 1% of the viewport width, and 1vh is 1% of the viewport height) are fairly well supported across browsers, in particular in all WebGL-compatible browsers. (There’s also an article on Viewport Sized Typography on Smashing Magazine that I highly recommend you to read.)

Finally, we’re playing with the opacity property of the background image to move it from 0 to 1 based on the current downloading process moving from 0 to 100%.

Oh, by the way, the text animations are simply done using CSS transitions or animations combined with a flexbox layout to have a simple but efficient way to display at the center or on each corner.

Handling all inputs in a transparent way

Our WebGL engine is doing all the work on the rendering side to display the visuals correctly on all platforms. But how can we guarantee that the user will be able to move inside the scene whatever the input type is used?

In the previous version of Babylon.js, we were supporting all types of input and user’s interactions: keyboard/mouse, touch, virtual touch joysticks, gamepad, device orientation VR (for Card Board) and WebVR, each via a dedicated camera. You can read our documentation to learn a bit more about them.

Touch is being universally managed with the Pointer Events specification propagated to all platforms via the jQuery PEP polyfill (generating Touch Events for the app when needed). To know more about Pointer Events, you can read on Unifying touch and mouse: how Pointer Events will make cross-browsers touch support easy

Back to the demo then. The idea for Sponza was to have a unique camera, handling all users’ scenarios at once: desktop, mobile and console.

We ended up creating the UniversalCamera. To be honest, it was so obvious and simple to create that I still don’t know why we didn’t do it before. The UniversalCamera is more or less a gamepad camera extending the TouchCamera which extends the FreeCamera.

The FreeCamera is providing the keyboard/mouse logic; the TouchCamera is providing the touch logic, and the final extend provides the gamepad logic.

The UniversalCamera is now used in Babylon.js by default. If you’re browsing through the demos, you can move inside the scenes using mouse, touch and gamepad on all of them. Again, you can study the code to see how exactly it’s done.

Synchronizing the transitions with music

Now, this part is where we’ve asked ourselves most questions. You may have noticed that the introduction sequence is synchronized with specific areas of the music playtrack. The first lines are displayed when some of the drums kick in, and the final ending sequence is switching quickly from one camera to another on each note of the horn instrument we’re using.

Synchronizing audio with the WebGL rendering loop isn’t easy. Again, this is the mono-threaded nature of JavaScript that generates this complexity. The articles on Introduction to the HTML5 Web Workers: the JavaScript multithreading approach share some insights behind that. It’s really important to understand the problem to understand the global issue we’re facing, but going into details here is outside of the scope of this article.

Usually, in demo scenes (and video games), if you’d like to synchronize the visuals with the sounds/music, you’re going to be driven by the audio stack. Two approaches are often used:

- Generate metadata that would be injected into the audio files, and that then could “call” some events when you’re reaching a specific part of it,

- Real-time analysis of the audio stream via FFT or similar technologies to detect interesting peaks or BPM changes that would again generate events for the visual engine.

Those approaches work particularly well in multi-threaded environments like C++. But in JavaScript, with Web Audio, we’ve got two problems:

- JavaScript, which is mono-threaded and, unfortunately, most of the time web workers won’t really help us,

- Web Audio doesn’t have any events that could be sent back to the UI thread even if Web Audio is being handled on a separate thread by the browser.

Web Audio has a much preciser timer than JavaScript. It would have been fantastic to be able to use this separate timer on a separate thread to drive the events back to the UI thread. But today, you can’t do that (yet?).

On the other side, we’re rendering the scene using WebGL and the requestAnimationFrame method. This means that, in “best cases,” we have 16ms windows timeframe. If you’re missing one, you’ll have to wait up to 16ms to be able to act on the next frame to reflect the sound synchronization (for instance to launch a “fade-to-black” effect).

I was then thinking about injecting the synchronization logic into the requestAnimationFrame loop. I studied the time spent since the beginning of the sequence and looked into the option of adjusting the visual to react on an audio event. The good news is that Web audio will render the sound whatever is going on in the main UI thread. For instance, you can be sure that the 12s timestamp of the music will arrive exactly 12s after the music has started playing even if the GPU is having a hard time rendering the scene.

In the end, we finally chose probably the simplest solution ever: using setTimeout() calls! Yes, I know. If you look into most articles out there, including the one I linked to above, you’ll find out that it’s quite unreliable. But in our case, once the scene is ready to be rendered, we know that we’ve downloaded all our resources (textures and sounds) and compiled our shaders. We shouldn’t be too annoyed by unexpected events saturating the UI thread. GC could be a problem but we’ve also spent a lot of time fighting against it in the engine: Reducing the pressure on the garbage collector by using the F12 developer bar of Internet Explorer 11.

Still, we know that this solution this is far from being ideal. Switching to another tab or locking your phone and unlocking it a few seconds later could generate some issues on the synchronization part of the demo. We could fix these problems by using the Page Visibility API, e.g. by pausing the rendering loop, various sounds and re-computing the next timeframes for the setTimeout() calls.

But maybe we’ve missed missed something; maybe, and even probably, there was a better approach to handling this problem. We’d love to hear your thoughts and suggestions in the comment section if you think that there’s a better way of solving the same problem.

Handling Web Audio on iOS

The last challenge I’d like to share with you is the way Web Audio is being handled by iOS on iPhone and iPad. If you’re looking for articles on “web audio + iOS”, you’ll find many people having hard time to play sounds on iOS. Now, what’s going on there?

iOS has a remarkable support of Web Audio — even the binaural audio mode. But Apple has decided that a web page can’t play any sound by default without a specific user’s interaction. This decision was probably made to avoid having advertising or anything else disturbing the user by playing unsolicited sounds.

What does it mean for web developers? Well, you first need to unlock the web audio context of iOS after a user’s touch — before trying to play any sound. Otherwise your web application will remain desperately mute.

Unfortunately, the only way I’ve found to do this check if by doing a user platform sniffing approach as I didn’t found a feature detection way to do it. That’s nothing short of a horrible, and not bulletproof techniques, but I couldn’t find any other solution that would resolve the issue. The code? Here you go!

If you’re not on iPad/iPhone/iPod, the audio context is immediately available to use. Otherwise, we’re unlocking the audio context of iOS by playing a code generated empty sound on the touchend event. You can register to the onAudioUnlocked event if you’d like to wait for it before launching your game. So if you’re launching Sponza on an iPhone/iPad, you’ll have this final screen at the end of the loading sequence:

Touching anywhere on the screen will unlock the audio stack of iOS and will launch the “show”.

So here we go! I hope that you’ve enjoyed a few insights behind the development of the demo. To learn more, read the complete source code of this demo on our GitHub. Obviously, everything is open sourced, and you can find main files on GitHub: index.js and babylon.demo.ts.

Finally, I really hope you’ll be now even more convinced that the web is definitely a great platform for gaming! Stay tuned, as we’re working on new demos at this very moment, and hopefully they will be quite impressive as well.

This article is part of the web development series from Microsoft tech evangelists and engineers on practical JavaScript learning, open source projects, and interoperability best practices including Microsoft Edge browser.We encourage you to test across browsers and devices including Microsoft Edge – the default browser for Windows 10 – with free tools on dev.microsoftedge.com, including F12 developer tools — seven distinct, fully-documented tools to help you debug, test, and speed up your webpages. Also, visit the Edge blog to stay updated and informed from Microsoft developers and experts.

(ms, vf, il)

(ms, vf, il)