We have a lot of passwords to remember, and it’s becoming a problem. Authentication is clearly important, but there are many ways to reliably authenticate users – not just passwords. Passwords are written off as inconvenient and unavoidable, but even if true a few years ago, that’s not true today. Due to a combination of sensors, encryption and seasoned technology users, authentication is taking on new (and exciting) forms.

Most other interaction patterns have been updated over time, but no one wants to mess with password authentication. It’s too serious. Or there’s too much liability. You know, like if you don’t clear the password input after someone types the wrong password, their credit card information is at risk.

I’m here to tell you it’s OK to rethink common password habits, and it’s acceptable to use common sense and due diligence to create usable, secure and error-free authentication – passwords or otherwise.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Why Passphrases Are More User-Friendly Than Passwords

- Better Password Masking For Sign-Up Forms

- Form Inputs: The Browser Support Issue You Didn’t Know You Had

- Auto-Save User’s Input In Your Forms

- Keeping Your Business And Clients Safe With Digital Policies

The Root Of The Problem

Password authentication doesn’t scale well. The more services we use, the more passwords we’re forced to remember. In the name of security, SaaS applications, social networks and other services enforce strict password rules that prevent honest people from signing in. Username/password authentication is apparently so effective that it’s a serious barrier to product and service use.

It’s not the passwords themselves; the problem is the scale at which people have to manage and remember usernames and passwords. It’s too much.

We don’t want to make our products less secure by relaxing our password standards, so what are our real options to safely and securely authenticate people and protect their sensitive information? There are a handful of ways today, and there are more coming. There are even things we can do to make traditional password authentication frictionless and user-friendly. Here are the options we realistically have today.

- Traditional username/password

- Passphrase

- Two-factor

- Social sign-in

- Passwordless

- Biometric

- Connected device

I’ll rate each method based on a few key factors:

- Implementation: how easy it is to set up and support

- Security: how hard it is for the wrong person to authenticate

- Usability: how easy it is for the right person to authenticate

In the spirit of rethinking obsolete password patterns, I’ll rate them in password strength meter terms (that is, vague descriptors with no stated reasoning).

Traditional Username/Password

| Implementation | strong |

|---|---|

| Security | weak |

| Usability | weak |

I’ll be honest. I have issues with the traditional username and password model. In a perfect world, I’d eliminate passwords altogether. However, in the real world, I use this method on 99% of the projects I work on.

Why? It’s important to remember that username/password authentication is the most understood authentication pattern, and it will feel the most trustworthy for a lot of people. There is a lot we can do better from a usability perspective, though. We can make it easier to create and recall passwords, and we can make signing in faster and less confusing.

Password recollection is mainly why I rated both security and usability as weak. It’s hard to create a secure password in the first place, and it’s hard to remember and use passwords after we’ve created them. Because of that, people create passwords that are too easy to guess, and then security is compromised. Ironically, the more security we impose, the less secure password authentication becomes.

Our industry needs to embrace a modern password authentication pattern. Mostly, we need think realistically about security and what best practices should be today. We can take advantage of technologies that didn’t exist when password patterns were formed, so we should do so in the name of user experience. By throwing away password security assumptions and building new ideas based on real data and modern use cases, there are many obvious improvements we can make to traditional password authentication. Here are just a few.

Limit or Eliminate Password Rules

A capital letter, lowercase letter, a number, and a symbol force people to create service-specific passwords.

In the US and UK, 73% of adults use the same password for everything. If that password doesn’t fit your service’s password rules, the account holder makes a unique password that they’ll promptly forget. Eliminating password rules will instantly increase password recollection and improve usability.

Why do we impose complex password rules in the first place? There are studies that show a long passphrase is more effective than a password with different types of characters, but I’ll get into passphrases later in the article.

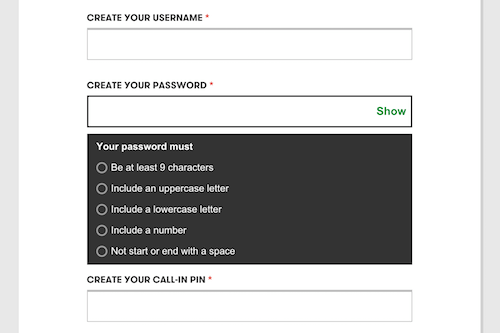

Use Password Rule Reminders

If you must use password rules, remind the user of your specific rules when they enter an incorrect password. If you require a capital letter and a symbol, the person signing in should know that as they try to remember their password. This is insanely helpful for users who have to remember a million passwords, and it’s only mildly less secure: a hacker can get the password rules by creating their own account.

This faux security pattern has been killing me for years, because although I keep better track of my passwords than most, I still forget them! Adding these reminders to a sign-in form is an easy way to greatly improve usability and increase sign-in success rates.

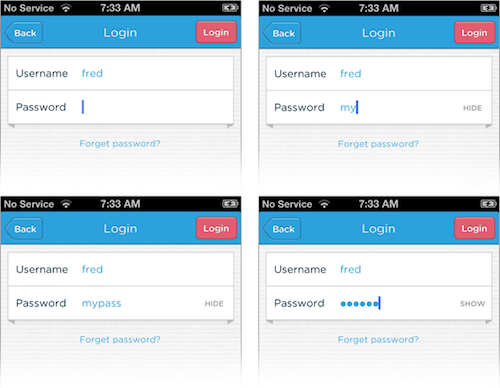

Show Password Typing with the Option to Hide It

This is pretty common for mobile devices, but we should do it everywhere (yes, including desktops). If someone is on a screenshare or giving a demonstration, they can hide their typing before entering their password. They’re the minority. Everyone else should be given the respect of seeing what they’re typing as they type it. These tweets about Yahoo’s and Sprint’s successes with this pattern should be proof enough that we don’t need to mask passwords anymore.

Luke Wroblewski gives an excellent overview of the thinking behind showing passwords and different ways to implement this pattern. Everything he describes is based around the idea that masking passwords is an outdated practice.

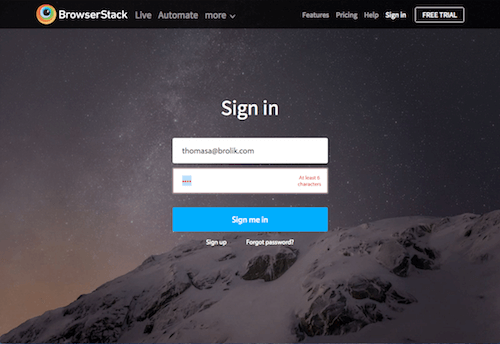

Be Specific with Error Messages

Tell your customer whether their username isn’t found or their password is wrong. (This has privacy risks, but unauthorized parties can usually get this information in other ways, like attempting to sign up.) At the very least, tell them if they entered a username, but you expected an email. People have multiple email addresses, usernames and passwords. Help them narrow it down a little.

If security is such an issue that you can’t let people know they’re trying the wrong email address, consider two-factor authentication instead.

Passphrases

| Implementation | strong |

|---|---|

| Security | good |

| Usability | good |

To take traditional username/password authentication a step further without introducing new use patterns or shaking up the status quo, consider passphrases instead of passwords. Passphrases are more secure than passwords, and they’re easier to remember. This has been written about for more than a decade (Passwords vs. Pass Phrases in 2005 through Why Passphrases Are More User-Friendly Than Passwords in 2015). The key that makes passphrases better for both security and usability is that people are much more likely to recall a phrase containing normal, human-readable words than a cryptic password. Therefore, we don’t need to write our passwords down, and we don’t need to use the same password for everything in order to remember it.

The widely held belief is that capitalization, numbers and special characters make automated password guessing harder, but it turns out it’s actually harder for a computer to guess a series of random (or seemingly random) words strung together to form one long phrase.

Need proof? Zxcvbn is a hackweek project from Dropbox that measures password strength. Other sites can use zxcvbn as an open source password strength meter, but Dropbox’s article on the project has some excellent stats and information about the true strength of different passwords. Read it for yourself, but essentially, “Tr0ub4dour&3” is much less secure than “correcthorsebatterystaple”. Test it out here.

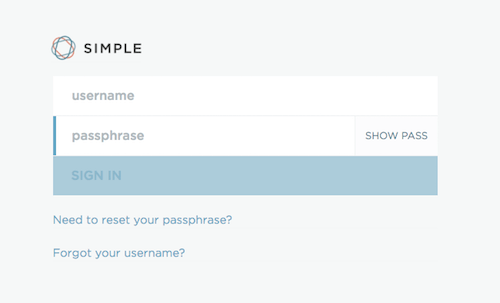

To use passphrases, we only need to suggest the passphrase idea to the user and eliminate password rules. People who want to use traditional passwords can do so if they please, but most people will try a phrase over a purposely unreadable password. It’s a good idea for usability either way.

Simple, the design- and tech-friendly online banking company, was my first experience with passphrases, and they’re kind of delightful. My passphrase is simple to remember and simple to type – especially on a mobile phone.

Two-Factor Authentication

| Implementation | weak |

|---|---|

| Security | strong |

| Usability | good |

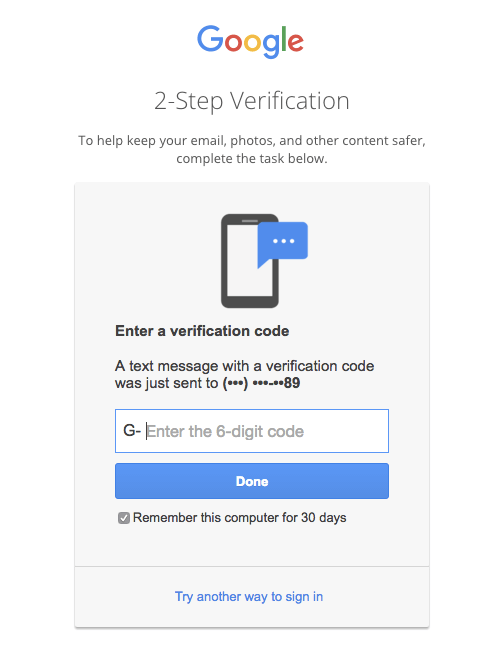

Two-factor authentication (2FA) is another extension of traditional password authentication, but after a username/password combination is verified, a unique code or URL is either emailed or texted to the person trying to sign in. They get authenticated by proving they have the unique code. This verifies access across multiple services, and it also alerts the account holder of malicious attempts to access their account.

Google provides an option for two-factor authentication in all (or almost all) of their services. In the case of Gmail or Inbox by Gmail, a unique code is texted. Other services send the code or link to an email address, which achieves the same goal.

Use two-factor authentication only where it makes sense – as you can imagine, 2FA can really annoy a person whose phone is upstairs or who’s not already signed into their email. If abused, 2FA is enough to make people abandon your service. Google handles authentication well. It uses a “trust this device for 30 days” feature. They also make 2FA an option and heavily encourage it, but they don’t force people to use it.

Another benefit of two-factor authentication is that we don’t need password rules because we’re not relying on the password as the only point of security. So, again, the password part can be more user-friendly than we’re used to.

Social Sign-In

| Implementation | strong |

|---|---|

| Security | good |

| Usability | strong |

Social sign-in, or other third-party sign-in, is a popular and convenient way to authenticate. It’s not just for signing in, either. American Express has Amex Express Checkout, where you sign in to your Amex account to securely pay for things on third-party sites. You’re authenticated, and you don’t have to send your credit card details to the merchant.

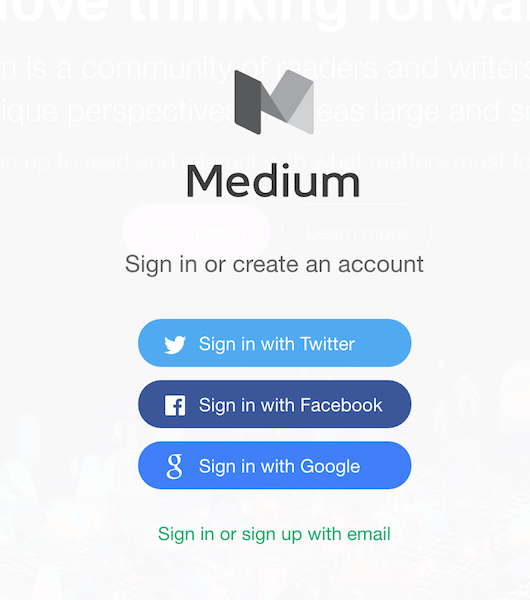

More commonly, though, social sign-in means signing in to a third-party service or app with Facebook, LinkedIn or Twitter. For a lot of services, this is a great way to authenticate. It’s convenient for the person signing in – if they have an account with the third-party service. For that reason, social sign-in always requires a fallback option.

Social sign-in also asks for permissions from the third party, which can be scary and deter users, and social sign-in doesn’t work behind firewalls that block the original site (like corporate offices).

Famously, MailChimp’s article from 2012 explains why MailChimp was (and apparently still is) against social sign-ins. Its argument is that social sign-in creates too many options for a user right at the top of the funnel. Even with a single social sign-in option and a traditional fallback, a user needs to remember how they originally signed up to sign in.

I agree with MailChimp to an extent, but today social sign-in is much more understood and accepted, due in large part to how common it is now. It’s often a great way to reduce authentication friction. I’d personally still suggest only a single, relevant option for third-party sign-in, but if companies like Medium are any indication, having several can be fine.

Passwordless Authentication

| Implementation | weak |

|---|---|

| Security | strong |

| Usability | strong |

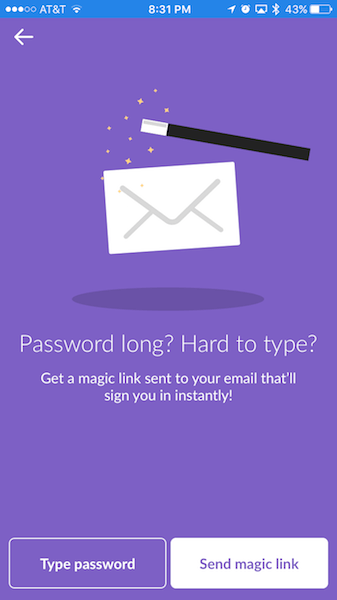

Passwordless authentication is two-factor authentication without the first step. The person signing in only has to remember their username, email or phone number, and they receive a unique code to complete the sign-in. They never create or enter a password.

We can take passwordless authentication a step further by skipping the manually typed code. Using deep linking or a unique token in the URL, a link in an email or text can directly open and sign in to a service.

For security, codes or links expire soon after they’re sent or after they’re used. This is what makes passwordless authentication better than password authentication. Access is granted exactly when someone needs it and is restricted any other time, but there’s no password to keep track of.

Slack has a really good example of passwordless authentication. At different phases in the sign-in and password reset processes, it uses what they call a “magic link” to authenticate users. A unique URL is sent to a person’s email, and that URL opens the Slack app and signs them in. Slack’s presentation of this interaction pattern is notable as well, because it brands the interaction as “magic” and makes it seem simple, secure and future-friendly. (Arguably, whoever coined “two-factor authentication” got the branding part wrong.)

Biometric

| Implementation | depends |

|---|---|

| Security | excellent |

| Usability | excellent |

Biometric authentication – fingerprints, retina scans, facial recognition, voice recognition and more – is where I see authentication ultimately going. The most common example is Apple’s Touch ID. This is the kind of thing that truly gets me excited. Biology is our true identity, and it’s always on us. We’re familiar with the idea of unlocking our phones or tablets with a fingerprint. However, biometric authentication is being used in other places (and with other biology) as well.

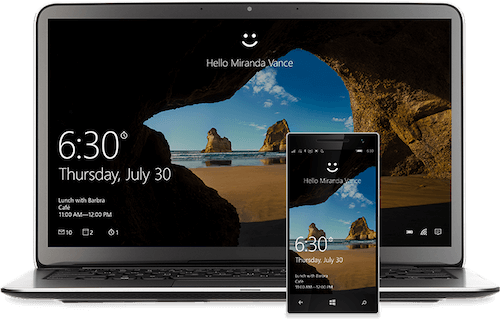

Windows Hello is a forward-thinking authentication system for Windows 10 that pairs cameras and sensors (on both computers and devices) to recognize faces, irises or fingerprints. The idea is that someone should open their computer and get right to whatever they want to do without sacrificing security. This type of authentication was barely possible until recently, especially on a Windows 10 scale.

Biometric systems require hardware and sensors to work, but luckily our mobile phones contain sensors for all kinds of different things. Hello uses infrared in the camera to detect faces and eyes (in any lighting condition), but they use mobile phones or tablets for fingerprint scanning. If desktops and laptops had prioritized security and sensors a bit more, we may have moved on from passwords years ago. Mobile prioritized security from the beginning, and now other hardware will catch up.

Biometric is early in its development, but there are some APIs and libraries that allow us to use biometric authentication today. These include BioID Web Service, KeyLemon, Authentify and Windows Biometric Framework API (what Hello is built on, I assume).

Connected Device Authentication

| Implementation | depends |

|---|---|

| Security | strong |

| Usability | strong |

Connected device authentication is a pre-established Bluetooth (or similar) connection from one device to another that has already authenticated someone. For instance, there’s an app for Mac OS X called KeyTouch that lets you sign in to your computer with your iPhone’s fingerprint scanner. There’s also Knock, where you knock on your phone to unlock your computer. You can imagine the possibilities as we accumulate more and more connected devices, especially in the IoT space where personal and possibly sensitive devices will be running all the time. Connected device authentication might become very useful.

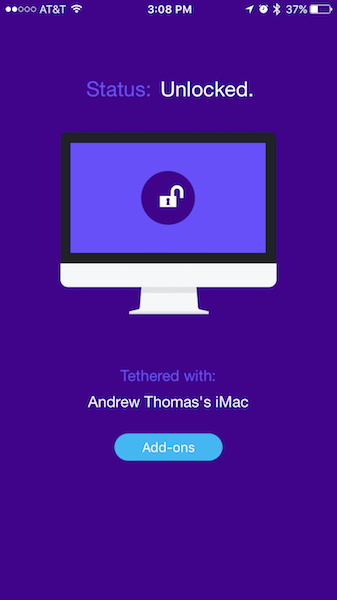

I use a Mac OS X + iOS app called Tether at my home office. After syncing your computer and phone once, the computer locks and unlocks based on the phone’s proximity to the computer. Tether has literally saved me hours of time. Typing my computer password, with capitals and numbers and a symbol, might take just three or four seconds, but doing it so many times each day, week, month, and so on… you get the idea. By the time I sit down in my chair, my computer is unlocked and opened up, thanks to connected device authentication.

Another example? Bluetooth car keys.

What Should We Do Now?

We ran a poll on Twitter, and it seems that among the options mentioned above, the good ol’ login/pass verification is still the most acceptable (49%), followed by social sign-in (28%). But just like everything else, we need to do what’s right for our users. We can work to eliminate the password problem by reducing the amount of passwords our services and apps require, and we can introduce some of these newer methods of authentication wherever possible. If there’s any way to reduce friction in the sign-in process, it needs to be considered.

If I had my way, we’d be done with passwords altogether. I believe they held us back a little before, but they’re really getting in the way now. A password revolution is coming.

However, we need to remember that people want to feel secure while signing in, and they need to know that their information is secure. If we push authentication too far, our users won’t trust it. Therefore, we won’t eliminate all passwords tomorrow, although we can reduce their scale.

The best authentication, like the best interface, is completely invisible. Therefore, the uncompromising goal should be to make authentication invisible. With that in mind, traditional password authentication – usability-enhanced or not – is not an option for very much longer. We can do better.

Hopefully we’ll see a day where authentication isn’t a roadblock, yet all of our information is secure. If you think about it, we’re not too far off. I predict the solution will be some form of biometric. Many others agree. Either way, if we keep pushing the envelope and investing in ultra frictionless, secure sign-in, the future state of authentication looks a lot brighter.

(da, vf, og, il)

(da, vf, og, il)