Cross-browser testing is time-consuming and laborious. However, developers are lazy by nature: adhering to the DRY principle, writing scripts to automate things we’d otherwise have to do by hand, making use of third-party libraries; being lazy is what makes us good developers.

The traditional approach to cross-browser testing ‘properly’ is to test in all of the major browsers used by your audience, gradually moving onto the older or more obscure browsers in order to say you’ve tested them. Or, if time and resources are short, testing a small subset of ad hoc browsers and hoping that the absence of a bug gives you confidence in the integrity of the application. The first approach embodies ‘good’ development but is inefficient, whereas the second embodies laziness but is unreliable.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Noah’s Transition To Mobile Usability Testing

- The Basics Of Test Automation For Apps, Games And The Mobile Web

- How To Create Your Own Front-End Website Testing Plan

- Where Are The World’s Best Open Device Labs?

In the next fifteen minutes, I hope to save you hours of wasted effort by describing a testing strategy which is not only less labour-intensive, but more effective at catching bugs. I want to document a realistic testing strategy more relevant and valuable than simply “test ALL the things!”, drawing upon my experience as a Developer in Test in BBC Visual Journalism.

Context

As an aside, it’s worth pointing out that we do more than just manual testing in our team. Cross-browser testing is no replacement for unit tests (Jasmine/QUnit), functional tests (Cucumber), and where appropriate, automated visual regression tests (Wraith). Indeed, automated tests are cheaper in the long run and are essential when your application reaches a certain size.

However, some bugs only manifest themselves in certain browsers, and test automation hasn’t yet reliably entered the domain of cross-browser testing. How can a computer know that your automated scroll event has just obscured half the title when viewed on an iPhone 4? How would it know that’s a problem? Until artificial intelligence grows to a point where computers understand what you’ve built and have an appreciation for the narrative and artistry you’re attempting to demonstrate, there will always be a need for manual testing. As something that must be performed manually, we owe it to ourselves to make the cross-browser testing process as efficient as possible.

What’s Your Objective?

Before diving blindly into cross-browser testing, decide what you hope to get out of it. Cross-browser testing can be summarized as having two main objectives:

- Discovering bugs This entails trying to break your application to find bugs to fix.

- Sanity-checking This involves verifying that the majority of your audience receives the expected experience.

The first thing I want you to take away from this article is that these two aims conflict with one another.

On the one hand, I know that I can verify the experience of almost 50% of our UK audience just by testing in Chrome (Desktop), Chrome (Android) and Safari (iOS 9). On the other hand, if my objective is to find bugs then I’ll want to throw my web app at the most problematic browsers we have to actively support: in our case, IE8 and native Android Browser 2.

Users of these two browsers make up a dwindling percentage of our audience (currently around 1.5%), which makes testing in these browsers a poor use of our time if our objective is to sanity-check. But they’re great browsers to test in if you want to see how mangled your well-engineered application can become when thrown at an obscure rendering engine.

Traditional testing strategies understandably put more emphasis on testing in popular browsers. However, a disproportionate number of bugs exist only in the more obscure browsers, which under the traditional testing model will not come to light until towards the end of testing. You’re then faced with a dilemma…

What do you do when you find a bug late in the long tail testing phase?

- Ignore the bug.

- Fix the bug and hope that you haven’t broken anything.

- Fix the bug and re-test in all previously tested browsers.

In an ideal world, the last option is the best one as it is the only way to be truly confident that all browsers are still working as expected. However, it’s also monstrously inefficient - and is something that you’d likely have to do multiple times. It’s the manual testing equivalent of a bubble sort.

We therefore find ourselves in a Catch-22 situation: for maximum efficiency, we want to fix all of the bugs before we begin cross-browser testing, but we can’t know what bugs exist until we start testing.

The answer is to be smart about how we test: fulfilling our objectives of bug-finding and sanity-checking by testing incrementally, in what I like to call the three-phase attack.

Three-Phase Attack

Imagine you’re in a war zone. You know that the bad guys are hunkered down in HQ on the other side of the city. At your disposal you have a special agent, a crack team of battle-hardened guerrillas and a large group of lightly armed local militia. You launch a three-phase attack to take back the city:

- Reconnaissance Send your spy into the enemy HQ to get a feel for where the bad guys might be hiding, how many of them there are and the general state of the battlefield.

- Raid Send your crack team right into the heart of the enemy, eliminating the majority of bad guys in one fierce surprise attack.

- Clearance Send in the local militia to pick off the remaining baddies and secure the area.

You can bring that same military strategy and discipline to your cross-browser testing:

- Reconnaissance Conduct exploratory tests in a popular browser on a development machine. Get a feel for where the bugs might be hiding. Fix any bugs encountered.

- Raid Manually testing on a small handful of problematic browsers likely to demonstrate the most bugs. Fix any bugs encountered.

- Clearance Sanity checking that the most popular browsers amongst your audience are cleared to get the expected experience.

Whether you’re on the battlefield or you’re device testing, the phases start off with minimal time spent and grow as the operation becomes more stable. There’s only so much reconnaissance you can do – you should be able to spot some bugs in very little time. The raid is more intense and time-consuming, but delivers very worthwhile results and significantly stabilises the battlefield. The clearance phase is the most laborious of all, and you still need to keep your wits about you in case an unspotted baddie comes out of nowhere and causes you harm – but it is a necessary step to be able to confidently claim that the battlefield is now safe.

The first two steps in our three-phase attack fulfil our first objective: bug discovery. When you’re confident that your application is robust, you’ll want to move on to phase three of the attack, testing in the minimum number of browsers that match the majority of your audience’s browsing behaviours, fulfilling objective number two: sanity checking. You can then say with quantitatively-backed confidence that your application works for X% of your audience.

Set-Up: Know Your Enemy

Don’t enter into war lightly. Before you begin testing, you’ll want to find out how users are accessing your content.

Find out your audience statistics (from Google Analytics, or whatever tool you use) and get the data in a spreadsheet in a format that you can read and understand. You’ll want to be able to see each browser and operating system combination with an associated percentage of the total market share.

Browser usage statistics are only useful if they can be consumed easily: you don’t want to be presented with a long, daunting list of browser/OS/device combinations to have to test. Besides, testing every possible combination is a wasted effort. We can use our web developer knowledge to heuristically consolidate our statistics.

Simplify Your Browser Usage Statistics

As web developers, we don’t particularly care which OS the desktop browser is running on – it’s very rare that a browser bug will apply to one OS and not the other – so we merge the stats for desktop browsers across all operating systems.

We also don’t particularly care whether someone is using Firefox 40 or Firefox 39: the differences between versions are negligible and the updating of versions is free and often automatic. To ease our understanding of the browser stats, we merge versions of all desktop browsers – except IE. We know that the older versions of IE are both problematic and widespread, so we need to track their usage figures.

A similar argument applies to portable OS browsers. We don’t particularly care about the version of mobile Chrome or Firefox, since these are regularly and easily updated – so we merge the versions. But again, we care about the different versions of IE, so we log their versions separately.

A device’s OS version is irrelevant if we’re talking about Android; what’s important is the version of the native Android browser used, as this is a notoriously problematic browser. On the other hand, which version of iOS a device is running is very relevant as Safari versions are intrinsically linked to the OS. Then there are a whole host of native browsers for other devices: these make up such a small percentage of our overall audience that they too have their version numbers merged.

Finally, we have a new wave of browsers rapidly rising in popularity: in-app browsers, primarily implemented on social media platforms. This is still new ground for us, so we’re keen on listing all of the in-app browser platforms and their respective OS.

Once we’ve used our domain expert knowledge to merge related statistics, we narrow the list down further by removing every browser that makes up less than 0.05% of our audience (feel free to adjust this threshold according to your own requirements).

Desktop browsers

| Chrome | Firefox | Safari | Opera | IE Edge |

| IE 11 | ||||

| IE 10 | ||||

| IE 9 | ||||

| IE 8 |

Portable browsers

| Chrome | Firefox | Android Browser 4.* | iOS 9 | IE Edge | Opera Mini |

| Android Browser 2.* | iOS 8 | IE 11 | Amazon Silk | ||

| Android Browser 1.* | iOS 7 | IE 10 | BlackBerry browser | ||

| iOS 6 | IE 9 | PlayBook browser |

In-app browsers

| Facebook for Android | Facebook for iPhone |

| Twitter for Android | Twitter for iPhone |

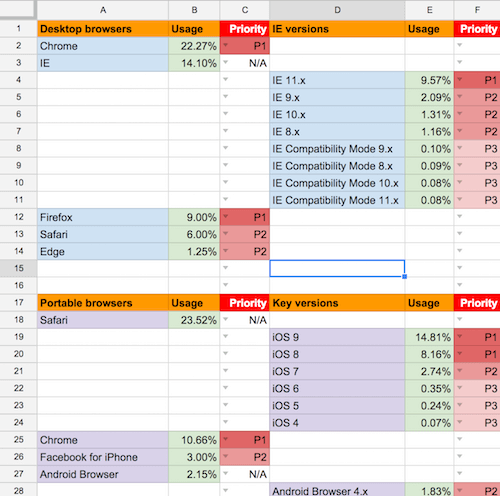

When you’re done, your spreadsheet should look a little like this (ignore the “Priority” column for now — we’ll get to that later):

So now you’ve got your simplified spreadsheet, showing key browsers from the web developer’s perspective, each associated with a total market share percentage. Please note that you should keep this spreadsheet up to date; updating once per month should be sufficient.

You are now ready to embark upon the three-phase attack.

1. Reconnaissance: Find Browser-Agnostic Bugs

Long before you even think about whipping out a device to test on, do the easiest thing you possibly can: open up your web app in your favourite browser. Unless you’re a complete masochist, this is likely to be Chrome or Firefox, both of which are stable and support modern features. The aim of this first stage is to find browser-agnostic bugs.

Browser-agnostic bugs are implementation errors which have nothing to do with the browser or hardware used to access your application. For example, let’s say your web page goes live and you start getting obscure bug reports from people complaining that your page looks rubbish on their HTC One in landscape mode. You waste a lot of time determining which version of what browser was used, using Android’s USB debug mode and searching StackOverflow for help, wondering how on earth you’re going to fix this. Unbeknownst to you, this bug has nothing to do with the device: rather, your page looks buggy at a certain viewport width, which just so happens to be the screen width of the device in question.

This is an example of a browser-agnostic bug which has falsely manifested itself as a browser-specific or device-specific bug. You’ve been led down a long and wasteful path, with bug reports acting as noise, obfuscating the root cause of the problem. Do yourself a favour and catch this sort of bug right at the beginning, with a lot less effort and a little more foresight.

By fixing the browser-agnostic bugs before we even begin cross-browser testing, we should be faced with fewer bugs overall. I like to call this the melting iceberg effect. We’re melting away the bugs which are hidden under the surface, saving us from crashing and drowning in the ocean - and we don’t even realise we’re doing it.

Below is a short list of things you can do in your development browser to discover browser-agnostic bugs:

- Try resizing to view responsiveness. Was there a funky breakpoint anywhere?

- Zoom in and out. Have the background-positions of your image sprite been knocked askew?

- See how the application behaves with JavaScript turned off. Do you still get the core content?

- See how the application looks with CSS turned off. Do the semantics of the markup still make sense?

- Try turning both JavaScript AND CSS off. Are you getting an acceptable experience?

- Try interacting with the application using only your keyboard. Is it possible to navigate and see all the content?

- Try throttling your connection and see how quickly the application loads. How heavy is the page load?

Before moving on to phase 2, you need to fix the bugs you’ve encountered. If we don’t fix the browser-agnostic bugs, we’ll only end up reporting lots of false browser-specific bugs later on.

Be lazy. Fix the browser-agnostic bugs. Then we can move onto the second phase of the attack.

2. Raid: Test In High-Risk Browsers First

When we fix bugs, we have to be careful that our fixes don’t introduce more bugs. Tweaking our CSS to fix the padding in Safari might break the padding in Firefox. Optimising that bit of JavaScript to run more smoothly in Chrome might break it completely in IE. Every change we make carries risk.

To be truly confident that new changes haven’t broken the experience in any of the browsers we’ve already tested in, we have to go back and test in those same browsers again. Therefore, to minimise duplication of effort, we need to be smart about how we test.

Statistical analysis of bug distribution

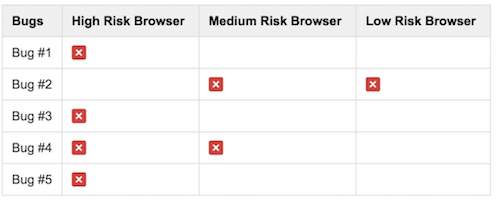

Consider the following table, where the cross icon means the browser has the bug.

Let’s say we’re to test our content in ascending order of risk: Low Risk browser, Medium Risk browser, High Risk browser. If it helps you to visualise this, these browsers might map to Google Chrome, IE 9 and IE 6 respectively.

Testing the Low Risk browser (Chrome) first, we’d find and fix bug #2. When we move to the Medium Risk browser, bug #2 is already fixed, but we discover a new bug: #4. We change our code to fix the bug – but how can we be sure we haven’t now broken something in the Low Risk browser? We can’t be completely sure, so we have to go back and test in that browser again to verify everything still works as expected.

Now we move on to the High Risk browser and find bugs #1, #3 and #5, requiring significant reworking to fix. Once these have been fixed, what do we have to do? Go back and test the Medium and Low risk browsers again. This is a lot of duplication of effort. We’ve had to test our three browsers a total of six times.

Now let’s consider what would have happened if we had tested our content in descending order of risk.

Right off the bat, we’d find bugs #1, #3, #4 and #5 in the High Risk browser. After fixing those bugs, we’d move straight on to the Medium Risk browser and discover bug #2. As before, this fix may have indirectly broken something so it is necessary to go back to the High Risk browser and re-test. Finally, we test in the Low Risk browser and discover no new bugs. In this case, we’ve tested our three browsers on a total of four different occasions, which is a big reduction in the amount of time required to effectively discover and fix the same number of bugs and validate the behaviour of the same number of browsers.

There can be a pressure on developers to test in the most popular browsers first, working our way down to the less widely used browsers towards the end of our testing. However, popular browsers are likely to be low-risk browsers.

You know you have to support a given high-risk browser, so get that browser out of the way right at the beginning. Don’t waste effort testing browsers that are less likely to yield bugs, because when you switch to browsers that do yield more bugs, you’ll only have to go back and look at those low-risk browsers again.

Fixing bugs in bad browsers makes your code more resilient in good browsers

Often you’ll find that the bugs that arise in these problematic browsers are the unexpected result of poor code on your part. You may have awkwardly styled a div to look like a button, or hacked in a setTimeout before triggering some arbitrary behaviour; better solutions exist for both of these problems. By fixing the bugs that are the symptoms of bad code, you’re likely to be fixing bugs in other browsers before you even see them. There’s that melting iceberg effect again.

By checking for feature support, rather than assuming a browser supports something, you’re fixing that painful bug in IE8 but you’re also making your code more robust to other harsh environments. By providing that image fallback for Opera Mini, you’re encouraging the use of progressive enhancement and as a byproduct you’re improving your product even for users of browsers which cut the mustard. For example, a mobile device might lose its 3G connection with only half of your application’s assets downloaded: the user now gets a meaningful experience where they wouldn’t have before.

Take care though: if you’re not careful, fixing bugs in obscure browsers can make your code worse. Resist the temptation to sniff the user-agent string to conditionally deliver content to specific browsers, for instance. That might fix the bug, but is a completely unsustainable practice. Don’t compromise the integrity of good code to support awkward browsers.

Identifying Problematic Browsers

So what is a high-risk browser? The answer is a little woolly and depends on the browser features your application makes use of. If your JavaScript uses indexOf, it might break in IE 8. If your app uses position: fixed, you’ll want to check it in Safari on iOS 7.

Can I Use is an invaluable resource and a good place to start, but this is one of those areas that again comes from experience and developer intuition. If you roll out web apps on a regular basis, you’ll know which browsers flag up problems time and time again, and you can refine your testing strategy to accommodate this.

The helpful thing about bugs you find in problematic browsers is that they will often propagate. If there’s a bug in IE9, chances are that the bug also exists in IE8. If something is looking funky on Safari on iOS 7, it’ll probably look even more pronounced on iOS 6. Notice a pattern here? The older browsers tend to be the problematic ones. That should help you to come up with a pretty good list of problematic browsers.

That being said, do back these up with usage statistics. For example, IE 6 is a very problematic browser, but we don’t bother testing it because its total market share is too low. The time spent fixing IE6-specific bugs would not be worth the effort for the small number of users whose experience would be improved.

It’s not always the older browsers you’ll want to test in the raid phase. For instance, if you have an experimental 3D WebGL canvas project with image fallback, older browsers will just get the fallback image, so we’re unlikely to find many bugs. What we’d want to do instead is change our choice of problematic browser based on the application at hand. In this case, IE9 might be a good browser to test because it is the first version of IE that supports canvas.

Modern proxy browsers (such as Opera Mini) may also be a good choice for a raid test, if your application makes use of CSS3 features such as gradients or border-radius. A common error is to render white text on an unsupported gradient, resulting in illegible white-on-white text.

When choosing your problematic browsers, use your intuition and try to pre-empt where the bugs might be hiding.

Diversify Your Problematic Browsers

Browsers and browser versions are only one part of the equation: hardware is a significant consideration too. You’ll want to test your application on a variety of screen sizes and different pixel densities, and try switching between portrait and landscape mode.

It can be tempting to group related browsers together because there is a perceived discount on the cost of effort. If you already have VirtualBox open to test IE8, now might seem like a good time to test in IE9, IE10 and IE11 too. However, if you’re in the early stages of testing your web app, you’ll want to fight this temptation and instead choose three or four browser-hardware combinations that are markedly different from one another, to get as much coverage over the total bug space as you possibly can.

Though these can vary from project to project, here are my current problematic browsers of choice:

- IE 8 on a Windows XP VM;

- native Android Browser 2 on a mid-range Android tablet;

- Safari on an iPhone 4 running iOS 6;

- Opera mini (only really worth testing with content that should work without JavaScript, such as datapics).

Be lazy. Find as many bugs as possible by throwing your app at your most problematic supported browsers and devices. With these bugs fixed, you’re then able to move onto the final phase of the attack.

3. Clearance: sanity checking

You’ve now tested your app in the harshest browsers you have to support, hopefully catching the majority of bugs. But your application isn’t completely bug-free yet. I’m constantly surprised by how different even the latest versions of Chrome and Firefox will render the same content. You still need to do some more testing.

It’s that old 80:20 rule. Figuratively, you’ve fixed 80% of the bugs after testing 20% of the browsers. Now what you want to do is verify the experience of 80% of your audience through testing a different 20% of browsers.

Prioritising the browsers

The simple and obvious approach now is to switch back to ‘traditional’ cross-browser testing, by tackling each browser in descending order of market share. If Chrome desktop happens to be the highest proportion of your audience’s browser share, followed by Safari on iOS 8, followed by IE11, then it makes sense to test in that order, right?

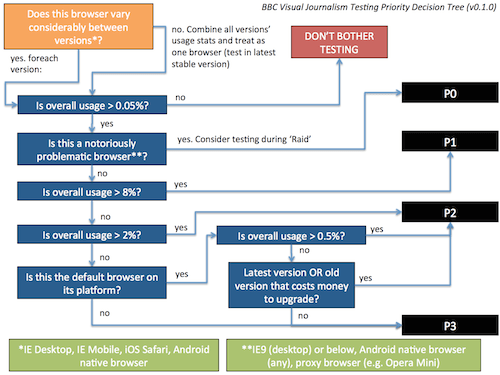

That’s a largely fair system, and I don’t want to overcomplicate this step if your resources are already stretched. However, the fact of the matter is, not all browsers are created equal. In my team, we group browsers according to a decision tree which takes into account browser usage, ease of upgrading, and whether or not the browser is the OS default.

Until now, your spreadsheet should have a column for the browser and a column for its market share; you now need a third column, designating which priority the browser falls into. Truth be told, this prioritisation work should have been done before launching the three-phase attack, but for the purposes of this article it made more sense to describe it here as the priorities aren’t really needed until the clearance phase.

Here is our decision tree:

We’ve designed our decision tree so that P1 browsers cover approximately 70% of our audience. P1 and P2 browsers combined cover approximately 90% of our audience. Finally, P1, P2 and P3 browsers give us almost complete audience coverage. We aim to test in all of the P1 browsers, followed by P2, followed by P3, in descending order of market share.

As you can see in the spreadsheet earlier in this article, we have just a handful of P1 browsers. The fact that we can verify the experience of over 70% of our audience so quickly means we have little excuse for not re-testing in those browsers if the codebase changes. As we move down to the P2 and P3 browsers, we have to expend ever-increasing effort on verifying the experience of an ever-diminishing audience size, so we have to set more realistic testing ideals for the lower priority browsers. As a guideline:

- P1. We must sanity-check in these browsers before signing off on the application. If we make small changes to our code, then we should sanity-check in these browsers again.

- P2. We should sanity-check in these browsers before signing off on the application. If we make large changes to our code, then we should sanity-check in these browsers again.

- P3. We should sanity-check in these browsers once, but only if we have time.

Don’t forget the need to diversify your hardware. If you’re able to test on a multitude of different screen sizes and on devices with varying hardware capabilities whilst following this list, then do so.

Summary: the three-phase attack

Once you’ve put in the effort of knowing your enemy (simplifying your audience stats and grouping browsers into priorities), you’re able to attack in three steps:

- Reconnaissance: exploratory testing on your favourite browser, to find browser-agnostic bugs.

- Raid: testing on your most problematic supported browsers on a variety of hardware, to find the majority of bugs.

- Clearance: verifying the experience of your application on the most widely-used and strategically important browsers, to say with quantitatively-backed confidence that your application works.

(rb, jb, al)

(rb, jb, al)