What’s your responsive design process like? Do you feel that it’s efficient? The following article is an excerpt from Ben Callahan’s chapter “Responsive Process,” first published in the eBook version of Smashing Book 5 (table of contents). We’ve collected some useful techniques and practices from real-life responsive projects in the book — and you can get your hard copy or grab the eBook today. You will not be disappointed, you know. —Ed.

“The successful respondent to this RFP will provide three static design options for our team to evaluate.” I’ve never been a huge fan of taking a multi-option design approach, but I get it — sometimes a client needs this.

“Each of these options will provide design for three unique layouts: home page, listing page, detail page.” All right. Now, we’re up to nine static design files. This is getting a bit out of hand.

“Each of these unique page designs should take mobile, tablet, and desktop sizes into account.” I was never great at math, but I can do this calculation. Twenty-seven static design files?! Not gonna happen.

This is a real-life request for proposal I received not too long ago. Turns out the client was very amenable to a more efficient approach. But this experience really got me thinking… The hardest thing about doing this stuff isn’t actually doing this stuff. It’s working with people while you do this stuff.

You see, almost every potential client out there already has a website. For us, that means most clients are coming to this with a set of expectations, along with their own baggage from past web projects. That baggage can have a drastic impact on how your client approaches the project — and you. To help diminish the negative effects of these expectations, I’ve found the best way to manage them is to be the one who sets them.

It’s my aim in this chapter to help you be more successful with your web projects by starting at the beginning; by working from day one to help set your client’s expectations about what’s going to happen, and by working throughout a project’s life cycle to do the same.

Key Differences In Process For Responsive Web Design

Before you open your favorite text editor, before you open Macaw, before you get your sketch pad out or start sculpting with text, you need to help your customer understand the process. There are many ways to do this, and my least favorite is to just try to sell them on a new process. In my experience, demonstrating value in your way of thinking early — even before a contract is signed — is the best approach. This gives your client the confidence that you know what you’re talking about, but it also means you need to earn their trust to try a new way.

To encourage this, there are four ideals my team and I try to keep in mind as we interact with each other: collaborate, iterate, adapt, and prioritize. Let me briefly explain why these specific ideas will keep you on the straight and narrow.

Collaborate

I know, I know. Everyone everywhere is talking about collaboration and how it’s needed to do great work. Well, you know what? It’s true. Of course, you need to collaborate within your team, but there’s another kind of collaboration that’s needed these days — collaborating with your client. I have an important reminder for you: clients are people, too. They may not have your expertise when it comes to web design and development, but they know a lot more about their business than you ever will.

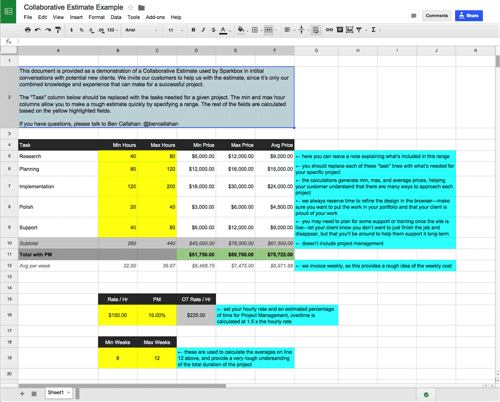

Again, it starts at the beginning. At Sparkbox, I’ve been looking for a way to be more collaborative in bringing new clients on board. As part of this, we’ve been taking a new approach to writing estimates. Instead of a customer coming to us and explaining their project so that we can disappear for a week and come back with The Perfect Solution™, we’ve been inviting them to help us with the estimate. It’s super easy — we call it collaborative estimation and clients love it.

We start with a basic Google spreadsheet that has a few adjustable fields and calculates what we think it will cost to do the work. We begin with wide ranges because we do this very early in the process — typically after just a 30-minute phone call. Then we share it with the client, and we work on it together.

Here’s why this is important: we collaborate on the very first thing we do with our clients. We want them to know that we add more value when we work with them rather than for them. This is just one way we put our money where our mouth is.

We also invite our clients into our team communication channels with us. We’re big fans of Slack and Basecamp. These tools provide a great mix of formal documentation and informal conversation, both of which are needed to facilitate quality collaboration.

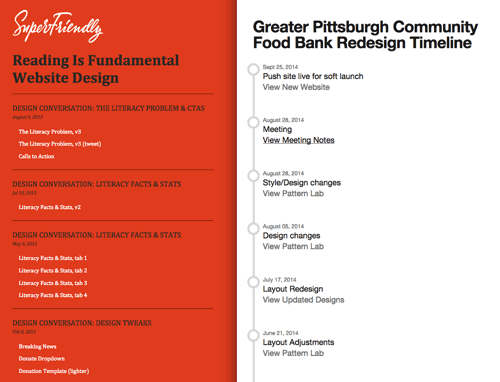

In Daniel Mall’s open redesign of the Reading Is Fundamental website, we all got a glimpse of how Dan brings his customers into the project with him. Brad Frost took it a step further with a GitHub project called “Project Hub” which is a tool for keeping track of the progress of your project.

Remember, these are all just tools. Tools can help, but what’s really needed is a change in how we think. My friend Kevin Sharon said something very poignant to me once. He said, “If you can’t say ‘No,’ it’s not collaboration.” I don’t know about you, but I’ve had many relationships with clients in which I didn’t have the authority to push back — even if I knew from experience what they were asking for would not work. These clients come to you with solutions rather than problems that need to be solved.

I’m ashamed to admit it, but I have also had client relationships where the opposite was true. Sometimes my frustration gets the better of me, and I forget that I need my client to be a part of the project. When we hear an idea from our customers and immediately disagree, we’re just as guilty as they at denying a collaborative process. Many web studios are not willing to allow this kind of collaboration in their process, often because they don’t believe their clients are creative or technical enough to contribute in a meaningful way.

Collaboration is a two-way street. Shifting your view of your customers toward them becoming true contributors in your work will result in all kinds of new ways to include them and help you create a better product.

Iterate

We regularly look for opportunities to deliver a small, high-quality subset of functionality at tremendous speed. Taking an approach like this demonstrates progress early and provides real opportunities to let what you’ve learned create momentum to carry you through a project.

If you sense that there might be political challenges in shifting how your client works, here’s a pro tip (and I sense this in every project we do): working iteratively can help turn skeptics into advocates. Most folks are much more likely to let you try a new way of working on a small phase than on an entire project. Again, the major point here is to demonstrate your value early to earn the trust of your customer.

One way iteration manifests itself is in prototyping. We are constantly looking for opportunities to identify a significant challenge, suggest a possible solution, prove or disprove its validity through prototyping, revise and repeat.

Often we look for the chance to start with a paid discovery phase before beginning a large project; think of it as dating before you get married. This gives you an opportunity to learn much more about the project and what it’s like to work with this client. Both parties are able to determine if the working relationship is a good fit.

Initial engagements can take many forms, but the primary objectives are to:

- Better understand the scope of the project

- Identify and prove possible solutions to the biggest challenges

- Figure out if the client/vendor fit is right

- Prove you are capable

- Get paid for the above

Your clients will appreciate this approach and you’ll be building a great foundation for future work. And if you learn something that dramatically changes your understanding of the project, you’ll only be committed to a small phase. This learning will greatly inform the next step in the process and push you toward a better solution.

We have a customer we’ve worked with for many years; in fact, we recently started our thirtieth project with them. To me, this is a sign that we’ve found a mutually beneficial way to work together — they see the value in what we offer, and we are creatively and technically satisfied in our work with them. In trying to pinpoint what has made this relationship successful, I keep coming back to our iterative approach. There have been many times when they’ve come to us with a problem and an idea for how to solve it. Instead of just biting off what may be a 12-week project, we’ve regularly suggested smaller, iterative phases that test out possible solutions and have a much lower initial investment. Taking this approach has allowed us to earn their trust. That trust is indispensable in creating a sustainable relationship, and iteration is at the core of it all.

Adapt

When responsive web design hit the scene, I can remember being struck by the idea that the flexibility inherent in the product we were building was working its way into our process. Samantha Warren said it best: “Your process should be as responsive as the products you are designing.”

The truth is, there is no perfect process for this kind of work. You and I need to embrace the constraints we’re presented with. Every project, client, scope, timeline, budget, team, tech stack, support matrix is different. The organizations that are successful in this business are the ones that can work within the constraints of a project and still do timeless work.

My views on process are decidedly difficult to explain to a customer. Given the opportunity, I’d probably lock a few key people (client included) involved with the project in a room for a few weeks and give them the mandate to figure it out. Take it from me, clients don’t like to be locked in a room for weeks at a time.

Instead, we have to find a balance between a very rigid process (where each step is laid out and documented) and an improvisational one (where we trust the team to find the best approach as they go). There are many factors to consider in finding this balance. Here are three to start with: the size of the team; the experience of the team; and the criticality of the project.

The Size Of The Team

It’s much easier to allow for great flexibility in process when you have a very small team. Two or three people sitting in the same room will be able to keep track of what’s happening without a lot of structure. Take the team size up to six or seven and it starts to get difficult to make sense of the impact of each player on the progress of the whole project. Increase your team to ten, fifteen, or more and it gets almost impossible.

This is very personal for me. When I first started Sparkbox with my partners, there were only four of us. We each had a fairly well-defined role, and we were able to operate fairly effectively without much process. Because we all sat in one big room together, there was constant communication about all aspects of our business.

Now, we have 23 full-time people, plus three apprentices. We certainly haven’t grown as fast as some places — we are very deliberate with our growth — but the phrase “growing pains” still rings true. We’ve had to experiment constantly with when, what and how to communicate. It’s only through this experimentation that we can find a balance that’s right for us.

The lesson here is that the size of your team affects the kind of process you can employ for a given project. Generally, the more people you have on a project, the more rigidity you’ll need. As your team size goes down, you can get away with a less formal process. It’s the responsibility of your project manager to monitor the pulse of the team and adjust the process to keep things moving smoothly.

The Experience Of The Team

When you are working with an inexperienced team, a more rigorous process will help keep everyone on the same page. In fact, I believe an inexperienced team needs a concrete process as context for gaining experience. Only after demonstrating success in a more rigid environment can you start to peel back the layers of process allowing a team more freedom in how it works.

This, again, is a fairly personal concept for me, mostly because of how we organize teams for a project. We put together a unique team for each project we take; even during the course of a project, it’s possible we’ll rotate people in and out of the team. This can create challenges, especially if the experience of those individuals is vastly different. Mostly, it’s meant that we need to be conscious of the fact that different people need differing levels of process to be successful. Our project managers monitor this closely and adjust as needed.

We have a lot of experienced designers and developers, so this balance is mostly about spreading out the less experienced folks. Adding one or two newer developers to a highly skilled team will raise the bar for everyone. The new devs will learn from the more experienced, and the more experienced will learn by teaching the new devs. This makes for a win–win!

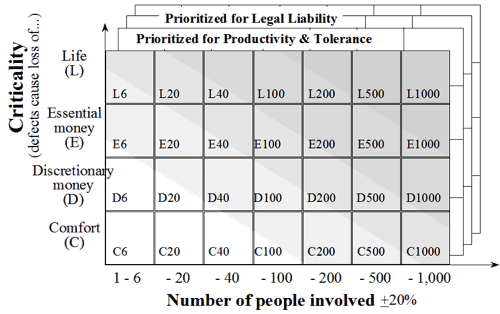

The Criticality of the Project

The idea of how critical the project is comes from a gentleman named Alistair Cockburn, one of the original signatories of the Agile Manifesto. In his writings on “Crystal Methods,” Cockburn describes the range of criticality by completing this statement.

Defects cause a loss of:

- Comfort (not critical)

- Discretionary money (somewhat critical)

- Essential money (critical)

- Life (very critical)

The more critical our product is, the more rigid our process should be. You might have experienced this if you’ve worked for both small and large businesses. Small, local companies tend to allow you more freedom in how you work because they have less at stake (lower criticality); large companies have much more to lose (higher criticality) if your process doesn’t produce good results.

When I was just getting started in this industry, I worked almost exclusively with small, local businesses. I managed projects with sticky notes, email and a phone call every other week. Now, I’m involved with much larger organizations. Managing these projects requires us to participate in daily stand-ups, retrospectives, and sprint planning meetings. We find ourselves building burn-ups, working in JIRA (issue tracking software), and calculating our velocity more than I care to admit. All of this is because of the criticality of the work — a small percentage of a big enough number is still a huge number. These larger companies understand this, and they have process in place to protect them from those formidable losses.

Prioritize

As the size of the screens we design for decreases, so do our options for communicating priority. Think about it: we typically use things like size, position, order and contrast to help users understand where they should focus. On a small screen, there’s only so much you can do with the size of an object or the position of a headline. We simply don’t have the same liberties as we have when our focus is on larger-screen experiences.

For this reason, it’s critical to understand the priority of content and functionality throughout a system. Luke Wroblewski brilliantly encouraged us to think about mobile devices first to help our clients home in on what is truly important. The truth is, without a solid understanding of priority, responsive web design is just guesswork.

We’ve encouraged this in our customers by making them think linearly very early in the process. (In the “Getting It Done” section below, I’ll share the kinds of tools we use to do this.) Thinking linearly has the benefit of requiring people to pick what’s most important, and it’s this priority that you need agreement on. Establishing this straightaway in your project will lay an accepted foundation to build on, and provide answers to many questions you’ll find yourself asking later in the project.

We recently had a project where our client came to us with widescreen wireframes already put together. They had done this in an effort to save some money, and we were happy to try to work with them in this way. When we started design, the client wasn’t happy with our work. It wasn’t until halfway through the project that we realized the widescreen wireframes didn’t adequately identify the priority of the content and functionality. This was the crux of the issues we were having. We ended up going back to perform some content analysis and prioritization to regain momentum on the project. Had we done that earlier, we could have worked more efficiently throughout the project. Unfortunately, in an effort to help them save money, we had to perform some rework which could have been avoided if we’d just laid the proper foundation first! Lesson learned — establish the priority early.

Four Ideals

As you jump into your next project, keep in mind that you need to include your client in the project. Look for opportunities to collaborate with them instead of just working for them. Remember that the more you demonstrate value early, the more trust you’ll earn. Iteration helps you do this — don’t be afraid to start small! Also, remember that you will most certainly have to adapt your way of working to better suit what a specific project or client may need. Finally, push hard to establish a priority of content and functionality early in the project. This will pay dividends later in the project when questions arise about the importance of certain kinds of content.

Beyond these four ideals, I’d like to provide a bit of a framework for you as you consider what kind of process will work in your day-to-day.

A Framework For Considering Process

Our Process Is Always Fighting For Its Life

One thing that amazes me about most presentations or writing on process is how confident the folks sharing seem to be. Maybe we’re the outlier, but our process is always fighting for its life. If a new way of working comes along, we’ll try it. If we think there’s even a hint of a better way to do something, we’re going to dig around trying to uncover it. This is just how we’re wired. I get the sense that a lot of you are wired this way, too.

Let’s agree that our process is never complete.

Shift Away From Linear Hand-offs

Most in the industry agree that we have to stop throwing deliverables over the wall. Instead, many are thinking about how to reorganize their teams in hopes that having the right people involved for the duration of the project will increase teammate empathy and raise the bar for everyone. Trent Walton describes this eloquently in his post called “Reorganization.” In it, he relates that the structure of your team often constrains the kind of process you can use and encourages us to consider smaller cross-discipline teams. We’ve seen this to be true and take a very similar approach. Truthfully, our past linear processes have probably always been a bit inefficient. I believe responsive web design has only made that inefficiency much more obvious; tackling responsive work has led me to conversations with our clients around their organizational structure — more evidence that RWD really is a catalyst for organizational change.

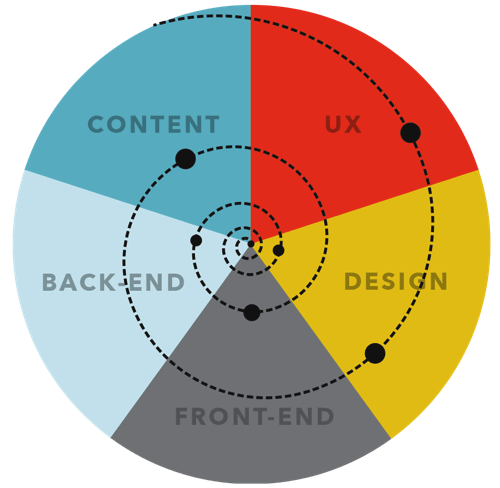

We need to involve more disciplines for more of the project. I like to think about this as spiraling through a project with our eyes firmly focused on the end product, on the one deliverable. With each spiral through, we involve all disciplines, and we gain more clarity at all decision points. The concept is simple: allow the entire team to play a role throughout the duration of a project. In other words, recognize and embrace the impact that making changes in one area of a project has on the others.

My team and I landed on this idea (spiraling through a project) because of our interactions with a business mentor of mine. His name is Geoff, and he’s a very sharp guy. He’s been the CFO of some pretty large organizations and has made a career out of helping visionary leaders get a grasp on their company’s financials.

When we first met with Geoff, we were in crisis mode. We had a major challenge before us, one that neither my partners nor I knew how to address. Geoff sat us all down and asked us to “begin with the end in mind.” He wanted us to explain what it would look like after we made it through the difficult times ahead. He wanted us to define success for this time in our company’s life. As we continued to meet with Geoff, I started to get frustrated. Each time we sat down, I hoped he would give us the advice we needed to start to solve the problem we were facing. Instead, he continually asked more and more questions. This went on for several weeks, and it was a difficult time for me.

I will never forget the meeting I had with Geoff and my partners where it all started to make sense. Our meeting began like all the others; we went through our current understanding of the problem before us and took some time sharing any new insight we had gained. Only this time, each of us started to see the solution emerging. It wasn’t perfectly clear, but it began to come into focus. Of the three options we were considering, one began to look much more appealing than the others. What we’d learned over the past months unmistakably led us to the best option to address the problem we were facing.

This lesson has been invaluable for me. What it taught me is that a linear process requires us to make decisions before we have all the information. How could we possibly know everything we need to know to create a set of wireframes without considering the visual design? How could we perfect the interface design without experimenting with some front-end code? When we act like it’s possible to start with the content, then do some user experience design, then do some user interface design, and so on, we ignore the impact that each of these deliverables has on the others. Instead, we need to allow them to inform each other. We need to give them room to breathe, to adjust, and to use what was learned from the project to carry them forward.

This is precisely the spiraling process that Geoff was pushing us through. Those weeks of asking questions were informing our understanding of the problem. Instead of making a decision (approving a UI design) and moving on as if it would never change (OK, front-end dev, go code this design), Geoff forced us to recognize that we didn’t have all the information we needed to make the best decision. Geoff wanted us to wait until the “last responsible moment” to decide.

I’ve tried to translate this idea of spiraling to what we do every day, and I’ve landed on a visualization like this:

Please put your own disciplines into the slices of pie above — the image is simplified to illustrate the approach. It’s important to note that those dots are not deliverables in the traditional sense. They represent opportunities for you to sit down with your client and review your progress toward the “one deliverable.” This means: stop refining deliverables for fear of disappointing your client. It’s terribly inefficient to make your wireframes look beautiful in Illustrator when a sketch on a whiteboard will do. We’ve even stopped calling them deliverables and started calling them updates.

This kind of workflow is flexible enough to use on any kind of project because you can simply swap out the types of disciplines that are needed for the project. The ceremony around the process can be made more rigid or more improvisational depending on the experience of the people involved. The key is to make sure all of the people are involved.

This approach delays decisions until you have the right information. It recognizes that decisions made by one discipline will undoubtedly affect the others. It opens the conversation to the team and requires buy-in from all involved. It’s less formal but more efficient. It’s less predictable, but I believe it has the potential to deliver a much better product.

Let’s agree that we need to seek out multidisciplinary contribution.

Efficiency Is Key

If we had all the time in the world, we wouldn’t have to worry about our process — we could just try stuff until we stumbled on a great idea. You and I both know this isn’t the case.

A lot of the adjustments we make to our process at Sparkbox are because we’re looking for a faster way to accomplish something. The promise of increased speed is also how we earn opportunities to work with some very talented internal teams at bigger customers. Everyone is looking for efficiency gains.

Let’s agree that a good process is also an efficient process.

Ever-Evolving. Multidisciplinary. Efficient. As we jump into the nuts and bolts of this stuff, I want us to keep these three things in mind. We can use these ideas as a filter through which we consider new approaches.

Enough Theory

That’s enough theory. Let’s get into the nuts and bolts of this work. I find myself constantly asking three questions throughout our web projects:

- Who are we building for?

- What do we want them to gain from the experience?

- How should we present the experience?

The goal is to find a way to say the right things (what) in the right way (how) to the right people (who). The secret to great communication of any kind is answering these questions. You will, of course, ask many other questions throughout your project. Questions like what kind of navigation patterns should I use on this site, or do we really need an ad at the top of every page? I’m suggesting that having the answers to who, what and how will lead you in the right direction as you answer all the other questions that come up.

Hopefully, you have already read Dan Mall’s chapter (just before this one). In it, he does a great job providing some context around understanding who you’re communicating with. His explanations of interviewing and kick-off meetings will move you solidly in the right direction.

Similarly, the next chapter by Eileen Webb is all about content strategy for your responsive project. It’s a thorough chapter, and she answers the questions around what it is we’re trying to communicate better than I ever could.

So, the rest of this chapter is dedicated to answering that third question, “How?” I’ll share with you the kinds of tools that have been the most helpful for me and my team at Sparkbox and trust that they will also help you!

Getting It Done

As I mentioned earlier, understanding the priority of the content and functionality we’re presenting is critical to communicating effectively. Here are a few ways this truth manifests itself in the work we do.

Content Priority Guide

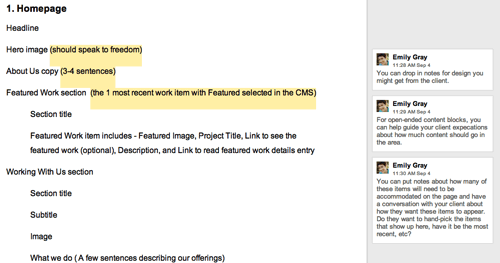

A content priority guide is “part content modeling, part stripped-down wireframe” (see “Content Priority Guide” by Emily Gray.); like a mini content model, in priority order, and with client collaboration. (See http://bit.ly/content-priority-guide for a working example of a content priority guide.)

The content priority guide tells you what types of content should exist on each page. These could be simple things like the title, primary image and body copy on a blog post, or they could be much more complex: consider all the content types you might need on the product detail page of an e-commerce site.

It also allows for explanation of each content type. If you have a short description of a product, the priority guide may say, “One sentence describing the product and what makes it unique.” For an item like a hero image, you could provide some details about the art direction of the photo if that was relevant for a specific case.

Content priority guides also help you quickly identify reusable components. This is very helpful as you plan out the management of that content — recognizing reusable patterns means you can build a more efficient system to manage the content.

Most importantly, a priority guide is in priority order. It provokes a discussion about what’s truly important on any specific page. This helps tremendously as you consider how a site will respond across viewport widths. And because it doesn’t contain actual content it facilitates great conversation about the what and why of types of content, which can easily be overlooked if you start writing the copy immediately.

If your clients have difficulty prioritizing (and they probably will), you could place these decisions around what is most important into a spreadsheet and give them options to check — primary, secondary, tertiary, etc. The result is the same: you have a prioritized list of content types for each page, but the process to get there may feel a bit more friendly to the client if they’re given some options.

Information Architecture

Once you have a good understanding of the types and priority of content that needs to exist in the system, it’s critical to consider how that content should be grouped and the paths through the content you want your users to take. This kind of thinking is crucial to the creation of a usable site.

I recently saw Aaron Quinn speak about information architecture and he said something that really stuck with me. He suggested that we might be relying too much on our common sense when it comes to grouping information. Instead, he made the case for us to consider consensus over common sense when planning how our users will interact with what we build. Let me explain why with a quick story.

We have a client we’ve been working with for over a year now. She has bootstrapped a very successful SAAS product which we helped her build. This woman is incredibly smart; she works on the web every day — it’s how she makes a living. Not too long ago, I was having a conversation with her about what was next for her product and she said this to me: “I think we need to make some changes to the tabs on our site.” I paused because I was desperately trying to remember where we had implemented tabs on her site. Sensing my confusion, she went on to explain more about what she was hoping for. After a few moments, I realized she was talking about the navigation. It was eye-opening that this savvy web entrepreneur referred to her navigation as “tabs.”

I tell you this because I want you to remember how much of a bubble we live in when we allow our instinct to drive the decisions we make. What may seem like common sense to you and me is likely a very different way of thinking about the web than pretty much all of our users. This is what Aaron Quinn was describing. We cannot rely on our instincts; we need to work with our users to find out how they think about the kinds of content we present to them. It’s very difficult to remember this, but it makes a world of difference.

Now, back to planning the information architecture of a site given this context. Instead of grouping content that seems related to you using common sense, Aaron is suggesting we rely on the consensus of users. Information architecture is a very deep field. I can’t pretend to cover the intricacies of this specialty in one section of one chapter. It’s important you understand that it’s impossible to do this kind of work well on an island. You must involve your client and the users of the site. Only then can you know if your intuition is correct.

Remove The Navigation

Let’s agree that a good process is also an efficient process.

Ever-Evolving. Multidisciplinary. Efficient. As we jump into the nuts and bolts of this stuff, I want us to keep these three things in mind. We can use these ideas as a filter through which we consider new approaches.

Enough Theory

That’s enough theory. Let’s get into the nuts and bolts of this work. I find myself constantly asking three questions throughout our web projects:

- Who are we building for?

- What do we want them to gain from the experience?

- How should we present the experience?

The goal is to find a way to say the right things (what) in the right way (how) to the right people (who). The secret to great communication of any kind is answering these questions. You will, of course, ask many other questions throughout your project. Questions like what kind of navigation patterns should I use on this site, or do we really need an ad at the top of every page? I’m suggesting that having the answers to who, what and how will lead you in the right direction as you answer all the other questions that come up.

Hopefully, you have already read Dan Mall’s chapter (just before this one). In it, he does a great job providing some context around understanding who you’re communicating with. His explanations of interviewing and kick-off meetings will move you solidly in the right direction.

Similarly, the next chapter by Eileen Webb is all about content strategy for your responsive project. It’s a thorough chapter, and she answers the questions around what it is we’re trying to communicate better than I ever could.

So, the rest of this chapter is dedicated to answering that third question, “How?” I’ll share with you the kinds of tools that have been the most helpful for me and my team at Sparkbox and trust that they will also help you!

Getting It Done

As I mentioned earlier, understanding the priority of the content and functionality we’re presenting is critical to communicating effectively. Here are a few ways this truth manifests itself in the work we do.

Content Priority Guide

A content priority guide is “part content modeling, part stripped-down wireframe” (see “Content Priority Guide” by Emily Gray.); like a mini content model, in priority order, and with client collaboration. (See http://bit.ly/content-priority-guide for a working example of a content priority guide.)

The content priority guide tells you what types of content should exist on each page. These could be simple things like the title, primary image and body copy on a blog post, or they could be much more complex: consider all the content types you might need on the product detail page of an e-commerce site.

It also allows for explanation of each content type. If you have a short description of a product, the priority guide may say, “One sentence describing the product and what makes it unique.” For an item like a hero image, you could provide some details about the art direction of the photo if that was relevant for a specific case.

Content priority guides also help you quickly identify reusable components. This is very helpful as you plan out the management of that content — recognizing reusable patterns means you can build a more efficient system to manage the content.

Most importantly, a priority guide is in priority order. It provokes a discussion about what’s truly important on any specific page. This helps tremendously as you consider how a site will respond across viewport widths. And because it doesn’t contain actual content it facilitates great conversation about the what and why of types of content, which can easily be overlooked if you start writing the copy immediately.

If your clients have difficulty prioritizing (and they probably will), you could place these decisions around what is most important into a spreadsheet and give them options to check — primary, secondary, tertiary, etc. The result is the same: you have a prioritized list of content types for each page, but the process to get there may feel a bit more friendly to the client if they’re given some options.

Information Architecture

Once you have a good understanding of the types and priority of content that needs to exist in the system, it’s critical to consider how that content should be grouped and the paths through the content you want your users to take. This kind of thinking is crucial to the creation of a usable site.

I recently saw Aaron Quinn speak about information architecture and he said something that really stuck with me. He suggested that we might be relying too much on our common sense when it comes to grouping information. Instead, he made the case for us to consider consensus over common sense when planning how our users will interact with what we build. Let me explain why with a quick story.

We have a client we’ve been working with for over a year now. She has bootstrapped a very successful SAAS product which we helped her build. This woman is incredibly smart; she works on the web every day — it’s how she makes a living. Not too long ago, I was having a conversation with her about what was next for her product and she said this to me: “I think we need to make some changes to the tabs on our site.” I paused because I was desperately trying to remember where we had implemented tabs on her site. Sensing my confusion, she went on to explain more about what she was hoping for. After a few moments, I realized she was talking about the navigation. It was eye-opening that this savvy web entrepreneur referred to her navigation as “tabs.”

I tell you this because I want you to remember how much of a bubble we live in when we allow our instinct to drive the decisions we make. What may seem like common sense to you and me is likely a very different way of thinking about the web than pretty much all of our users. This is what Aaron Quinn was describing. We cannot rely on our instincts; we need to work with our users to find out how they think about the kinds of content we present to them. It’s very difficult to remember this, but it makes a world of difference.

Now, back to planning the information architecture of a site given this context. Instead of grouping content that seems related to you using common sense, Aaron is suggesting we rely on the consensus of users. Information architecture is a very deep field. I can’t pretend to cover the intricacies of this specialty in one section of one chapter. It’s important you understand that it’s impossible to do this kind of work well on an island. You must involve your client and the users of the site. Only then can you know if your intuition is correct.

Remove The Navigation

During some recent usability tests, I noticed that on small screens many users never attempted to locate or use navigation. These days, most of our small-screen navigation experiences are hidden behind obscure icons (hamburger, anyone?). I believe our expectation that users will properly identify, trigger and use our navigation is unfounded.

In an effort to combat this, we’ve begun considering a simple question — can someone use this site without the navigation?

Literally, remove the navigation from your site and see if your users can reach the content they want. In other words, plan out the content in such a way that your users can feel their way through the experience. Chances are, a good number of them will browse this way. We’d better be ready for them.

Style Comparisons

I learned about style comparisons when I had the opportunity to present with Dan Mall and Yesenia Perez-Cruz at Artifact Conference in Austin, Texas. Dan shared a story about how he was working to build a new office. Here’s the relevant excerpt from his blog post:

“I could create an illustration or a 3D rendering of what I want my new office to look like, but that doesn’t take advantage of his [the contractor’s] great ideas. It’s dictation, not collaboration. Instead, I show him a Pinterest board my wife and I created. I tell him that I love these beams or this mix of materials, and we can have a conversation. I revise my ideas through his expertise, and vice versa. This is how building a website should go.”

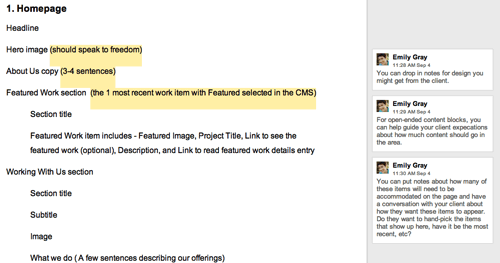

Not only is this a brilliant approach to building a new space, it can be applied directly to what we do each day. Our creative director, Jeremy Loyd, has been creating super-simple PDFs for our clients that ask them whether they think their brand would best be represented online with:

- A dark or a light site

- A flat or a textured site

- An illustrated or photographic site

- Whatever other style comparisons are relevant

You get the idea. The point is that it only takes a few minutes to put this together, because it doesn’t really require any design. You can use screenshots of existing sites that embody the qualities you have questions about.

An approach like this is very useful when there isn’t much clarity about the design direction up front. It helps us make sure we’re in agreement about the direction we’re headed. Truthfully, this is really just a simple tool to facilitate a conversation, to get people thinking and conversing about design.

One other trick from my friend Dan Mall which you can use to really drive this home is to quickly edit your client’s logo into a screen capture of someone else’s site. There is something about seeing their brand associated with a specific style which provokes a reaction. This makes for very fruitful conversations.

User Experience Design

No title in our industry is more overloaded and misunderstood than “user experience designer.” It means so many different things to so many different people. Recently, I’ve even noticed a trend toward expecting all designers and developers to do this work. And while I believe the best organizations have teams full of people who care about user experience, I also believe it has a deeper role to play.

I think about user experience as the glue that binds our design and our development together. It’s what separates web design from other kinds of design — that our work is intended not only to be observed, but also to be interacted with. That interaction is so important. In my mind, a great user experience designer has an instinct for what will be easy for a user to understand. However, this must be balanced with the idea that design without testing is guesswork. For this reason, a great user experience designer knows how to research their users, how to collaborate with UI designers, how to prototype possible solutions, and how to select and execute usability studies to capture and analyze data which properly informs design and development.

That’s a lot. And since I’m not formally trained in user experience or human factors, I’m probably not qualified to write about each of those things. Instead, I want to focus on one lesson I’ve learned (see “Test the Aggregate”) and then share the kinds of updates we do with our customers to help us all agree on usability decisions across screen sizes and input methods.

Test The Aggregate

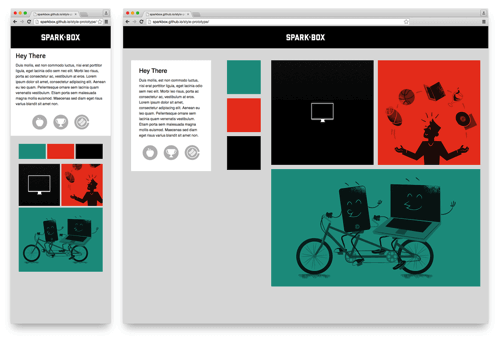

I work with internal user experience teams at larger clients, and one challenge I’m continually presented with is the desire to test the experience they are building at individual breakpoints. In other words, I’ve seen teams create three (or more) separate prototypes — for mobile, tablet and desktop — and then proceed to test each one independently. When this happens, each of these separate experiences will evolve on its own, usually resulting in three unique experiences which will be very difficult (if not impossible) to build in a responsive way.

To combat this, lately I’ve shared how critical it is to test the aggregate experience. Instead of building three separate prototypes for usability studies, build a single prototype with HTML and CSS that actually responds. We usually do this statically with an evolving set of front-end build tools (you can learn more about our front-end stack in the article “We Heart Good Tools: An Update on Our Build Process”) which means we can work quickly with fake data.

This concept is about letting go of the control you think you have. It’s about making decisions which benefit the whole (the aggregate) even though they may require compromises in certain contexts. It recognizes that changes made at one of the breakpoints in your system will inevitably affect the experience at other breakpoints. It’s about embracing the benefits you get with a single code line and adjusting our usability studies to account for this.

If we’re building responsively, we need to focus on testing a single-site solution across viewport widths. We need to measure the usability of the whole, not just the breakpoints. This will help us create the most usable experience for the most people.

And now, a few updates we use with our clients to help accomplish these goals.

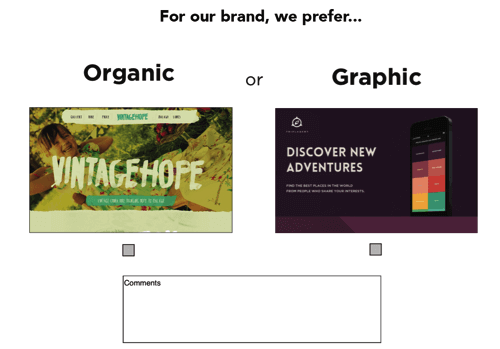

Content Prototype

You’ve heard it said that a web designer should learn some CSS, right? Well, I agree, and I think a content strategist should learn some HTML. For this reason, and many others, we’ve been building content prototypes pretty early in our web dev process. As soon as we start to get a clear picture of actual content, we start marking up that content with hypertext. This is what we do with HTML, right? Who better to wrap content in semantic tags than the folks who best understand the content? While tools like Markdown can work as well, I think it best to learn some basic HTML before you jump straight to Markdown. Understanding why you’re writing the content in this way is just as important as actually writing the HTML. Tools like Markdown add a layer of abstraction between your actions and the output of those actions — an abstraction that is fine, once you understand what it gives you.

When we create a content prototype, we intentionally leave out almost all styles. We leave them quite ugly, so it’s very clear we have not designed anything. This keeps the conversation focused on the content and the priority of that content. Know that when you show this to a customer, they will immediately home in on the order of things — which is precisely what you want them to do: get that priority right! Also, we usually include just enough CSS to show groupings, like so:

I told you it was ugly.

We also flood our content prototypes with links. One reason we create these is to allow people to navigate from page to page, to see if the flow through the content works.

Remember, you have to prepare your clients for seeing this kind of ugly update. Otherwise, they will certainly have second thoughts about involving you in their project. However, there’s something powerful about seeing raw content marked up in a browser.

One important note: we recognize that purely semantic markup is probably not what will go to production. While this would be ideal, the reality of work on the web today is that it needs to be maintainable and extendable by individuals and teams with wildly varying skill sets. However, starting with this pure version of the markup is a fantastic way of reminding us of our ideals. Then, as we adjust the markup to allow for styling, reusability, extendability and so on, we’re very aware that every change we make moves us away from the ideal. Every change is a compromise and should be deeply considered as such before it’s made.

Static Wireframes

The past few years have seen quite a bit of distaste for more traditional static wireframes. I believe they can still add a lot of value. I also believe they may not be needed on every project. When we use them, we typically do them at narrow widths — as inconvenient as this is — to help us focus on priority. Limiting our visual real estate forces this focus. We’ve used a lot of tools to do this, everything from Keynote to Balsamiq. Honestly, any of these tools will do the job. Find one you’re comfortable with and get to work.

We also do a lot of sketching. Whiteboards, pencil and paper, various sketching apps. We take pictures of this stuff and share it with our clients, intentionally keeping it all very raw. The rawness is an important part of what we do. It helps our customers know we’re not wasting time polishing documents that won’t benefit from polish, and it keeps the feedback focused. The last thing we want is someone commenting on the colors of our wireframes.

Interactive Wireframes

Part of the push away from more traditional wireframes has been in favor of a more interactive approach. Like the Agile Manifesto promotes working software over documentation, many in our industry believe that demonstrating your intention for an interaction via a prototype is much more powerful than trying to describe it statically. These days, the tools available for rapid prototyping are tremendously capable: frameworks like Bootstrap and Foundation; CSS (or Sass and LESS) toolkits like Bourbon and Pure CSS; visual prototyping tools like InVision and Marvel. Even visual web design and development tools like Macaw or presentation tools like Keynote can be used to create very interactive wireframes.

The benefit of this approach is that you can show people the idea instead of trying to explain it to them. If a picture is worth a thousand words, a prototype is worth a thousand pictures.

We’re working with an organization now that understands this. One of their goals is to bring rapid prototyping earlier into their process so they can use the prototypes for usability studies, as well as production code. Our work with them is focused on creating a system of components which can be used across all of their web properties. This system will also eventually be used to allow their team to build interactive wireframes very quickly. Because we will have built it with their brands in mind, the interactive wireframes will look very much like their production releases, which will be tremendously helpful in their UX testing.

This kind of approach focuses on the long-term success of a web property. It embodies the “one deliverable” workflow we talked about earlier by involving all disciplines in the creation of the prototype, and allowing what is learned during its design and development to inform further decisions. I believe we’re seeing a shift toward organizations building mature front-end systems instead of hacking together CSS as an afterthought. Giving an organization the ability to test a static version of their web work with real users is a major step toward cementing this as a norm in the near future.

UI Design And Development

“Good design is problem solving.”

— The Art and Science of Web Design, Jeffrey Veen (2000).

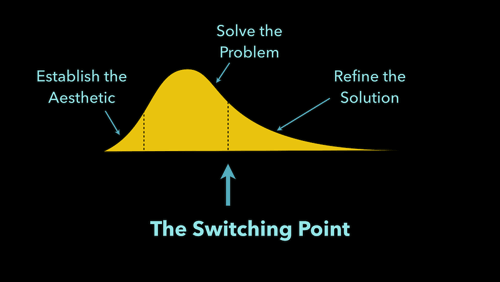

For those of you who are designers, this quote rings very true. Many folks see what we do as decoration, but it’s so much more. Over the past few years, I’ve found myself wholeheartedly agreeing with the sentiment of Jeff’s statement, but also intensely aware of designers’ tendency to overrefine their solutions. This leads me to what I call “the switching point.”

If you break the activity of design into three phases — establishing the aesthetic, solving the problem, and refining the solution (as indicated above) — the shift from problem-solving to solution refinement is the switching point. This is the last responsible moment to move into the medium of the web. If you don’t do this, you’ll end up performing that refinement phase multiple times — and that is highly inefficient.

If you’ve ever spent hours tweaking a PSD, handed it over to a dev to build, and then checked back in a week or two, you have experienced this pain. All the effort you took to refine and refine by pushing static pixels around is wasted. As soon as the design changes media (from static design in Photoshop or some other tool to HTML and CSS in the browser) another pass of refinement is needed. The idea behind the switching point is to recognize how inefficient this is. Instead of refining with static tools, get the basic design coded as soon as possible and handle the refinement in the end medium — the web.

This often requires design pairing, literally sitting together to make those refinements come to life. Though this can feel slow and painful at times, it is actually tremendously beneficial to all involved. As a designer shares with a front-end dev the kinds of style adjustments they would like to see, the front-end dev learns what is important in a refined design. While the front-end dev makes the requested changes, the designer sees how those changes are made, perhaps learning a little CSS. This process makes everyone smarter. It also means that the next time these two pair, it will go much faster.

These days, we have to be comfortable with a number of tools to get UI conversations started and we need to shift the coding of those designs earlier in the process. Let’s take a look at a few ways to do this.

Style Tiles

Samantha Warren broke new ground when she introduced style tiles as a way to “define a visual language” for the web. Those of us with branding backgrounds immediately saw how valuable style tiles could be.

Style tiles are quite simple. They generally include color palettes, typography choices, textures, and iconography or illustration styles. They are deliberately not a full-page comp. Instead, they represent just enough design to determine if we’re moving in the right direction. For this reason, they work best when your client has expressed what they want, but you aren’t fully convinced you’re on the same page.

I’ve come to appreciate style tiles, mostly because of their speed. Where we used to spend a week designing a homepage and subpage in Photoshop, we can now create a simple style tile in a matter of hours. This can save time and money, and give you confidence that you’re moving in the right direction.

Samantha has a handful of examples on the style tiles site, and there are a few great resources listed below which cover their use in real-world process:

- “Get Your (Visual) Style On”: Yesenia Perez-Cruz, Dan Mall and my presentation at Artifact Conference in Austin, Texas (May 13, 2013).

- “Faster Design Decisions with Style Tiles”: Samantha Warren at An Event Apart in Austin, Texas (February 2015).

- The Style Guide Podcast with Samantha Warren

Because of their static nature, we don’t use them too often. Our initial design direction is typically established with an element collage or a style prototype, both covered next.

Element Collages

Dan Mall introduced us to element collages as “an assembly of disparate pieces without specific logic or order.” Their variegated nature makes it obvious that what you’re looking at is not a finalized design; rather, element collages provide clients with the context of a variety of components that might live in a system together. They help us put some flesh on the bones of a wireframe; they help us picture the direction we’re moving in; they allow us to begin visualizing the building blocks of our site but encourage us not to lose sight of the whole.

One benefit of element collages is that you can choose which components to show. Does your client really care about how search is presented to their users? Great! Maybe you should spend some time addressing that concern — put it in the element collage. Is your client obsessive over the call to action buttons? Put them in the element collage. This pick-and-choose mentality makes it easy to tailor each collage with what’s most important in your project. Your clients will appreciate this tremendously.

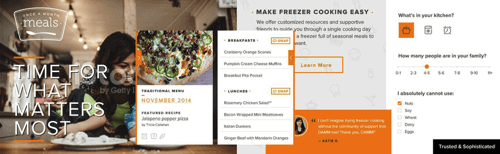

On a recent project, we needed to establish the design direction for a redesign of one of our client’s web properties. Katie Kovalcin (one of our designers) was leading the design effort of our team, and she opted to create two element collages instead of doing homepage comps.

The total time we invested in creating these two design concepts was around 16 hours. When I asked Katie how long this would have taken had she been asked to do two homepage comps, she responded:

“In this step, trying to figure out their new aesthetic, it would be hard to juggle finding that aesthetic while trying to lay out the hierarchy of the page and figure out the interactions, too. So, to lay out the whole homepage as a way to figure out the aesthetic could sometimes take up to a week, depending on how much we had to work from. I’d say probably close to 25–30 hours each.

But going off of the element collage, it was pretty easy to move forward with the page layout and all of that other stuff because there’s not a lot of scrambling to figure out what button styles we’re going to use, or fonts, or colors.”

That means, by using an element collage, we quartered the amount of time we put into establishing an aesthetic.

There’s one other really interesting expression in Katie’s quote above; she said “it would be hard to juggle finding that aesthetic while trying to lay out the hierarchy of the page and figure out the interactions, too.” In other words, starting with a homepage comp is trying to accomplish too much, too soon. When we take a smaller step first (by using element collages or style tiles), we’re able to divide and conquer the design challenges before us. This brings our clients into the conversation more frequently and allows us to learn as we go, all resulting in better work.

Style Prototypes

You can think of style prototypes as interactive style tiles. The same types of things you might include in a style tile — brand mark, headlines, paragraph styles, button styles, link treatment, color recommendations — are included with a style prototype. The only difference is that we take it one step further and code it.

The beauty of these is that we can show real web type, real colors, real hover states, illustration style with web vectors, and how type and basic layout might respond. We ask our clients to review them in their browser of choice. This opens up conversations about what it means to support a browser. For example, if they use a browser that doesn’t support border-radius, they won’t see rounded corners.

We can also build style prototypes in around a day, which gives us the same efficiency benefits a style tile gives us. Clients love them because they can interact with them. They can see them on their phones and tablets. They can start to play with them.

Finally, in a world where most of us believe web designers should learn to code, style prototypes are a fantastic introduction to writing HTML and CSS. Because of their simplicity, even a non-coding designer can figure out how to build them. Before they know it, they’ll have the confidence to refine production CSS, instead of statically mocking up the changes they want to see.

When we designed the original Sparkbox site, and when we recently redesigned, we used style prototypes to establish a design direction.

Atomic Design

Jeremy Keith first introduced me to the idea of starting design with “the atoms of a site” during his Breaking Development keynote entitled “There is No Mobile Web.” Brad Frost formalized the term back in June 2013 when he outlined a mental model for approaching the design of a “system of components” for the web.

The basic premise is that we should consider five levels of granularity in our work to craft reusable systems of components. The smallest level is called an atom; think of a simple HTML input or a label for an input. These atoms can be combined into molecules; perhaps a search molecule is made up of a button, label, and input. These molecules can be combined to form organisms; maybe the header of a website would contain the search, brand and navigation molecules. These organisms are put together to form templates and pages. Templates are full of generic data; pages are templates which have real data injected into them. All of this theory can help us create more modular, reusable and extendable code.

One thing I’ve learned as we’ve approached our projects along this line of thinking is that atomic design is much easier when you allow it to evolve out of refactoring. A common way for us to work is to build a small component in HTML and CSS without much worry about the atoms, molecules or organisms. Then, once we’ve solved the UX and UI problem with an interface, we can refactor that code into an atomic structure. This reverse approach means we don’t waste time attempting to overthink what should be a molecule versus an organism. Instead, we allow the various levels to evolve as the system itself evolves.

The result of an atomic approach is a library of patterns which can be integrated into a system.

Pattern Libraries

A pattern library is just what it sounds like — a library of the patterns that exist in your system. There are a lot of people working on pattern library solutions these days; folks like Brad Frost, Anna Debenham, Jina Bolton, and Bermon Painter have spoken and written about the topic. In fact, Brad and Dave Olson have created one of the more well-known tools available today, Pattern Lab. Pattern Lab is great because it allows you to separate the specific content from the HTML modules, and it provides an atomic framework which makes it easy to build up a system of patterns. They’ve also added in some great features for testing while you’re in development. The whole thing is very easy to get running locally and has a simple interface that can easily be shown to a client. If you’re looking to get into pattern-driven design, this is a fantastic place to start.

A lot is happening in this space right now, and there are many other resources for those of us interested in learning more. Brad has worked with Anna Debenham and Brendan Falkowski (along with a few other folks) to create Website Style Guide Resources. This is a tremendous collection of many of the examples, articles, talks, podcasts and more that cover pattern-driven design and development.

So far, the biggest challenge is finding a way to keep a pattern library up to date after the patterns have been integrated with a back-end system. I haven’t seen the perfect solution for this yet, but there are a lot of bright minds working on it. Check out Rizzo by Lonely Planet as a great example of an organization diligently working to solve this very problem. Even if we don’t have a perfect long-term solution, I’ve seen tremendous benefits from designing this way. It keeps you thinking modularly, and this makes the front-end work we do much easier to integrate and maintain.

What About Breakpoints?

Whenever I speak or write about process, I’m always asked about selecting breakpoints. Strangely, this conversation almost never arises in our responsive work from day to day. Certainly, some clients come to us having done a ton of work reviewing analytics and prioritizing devices — all in the name of documenting the system’s breakpoints. This line of thinking has never made much sense to me.

I believe it was Stephen Hay who said it first: “Start small and add a breakpoint when the site breaks.” Our sites often have dozens of breakpoints — most of them don’t align with common device sizes. When you see that your content and your design are no longer working in harmony, fix it.

Now, there is a difference between what Stephanie Rieger calls major breakpoints and minor breakpoints. (I’ve also heard them called breakpoints and tweakpoints.) Let me explain each.

Major Breakpoints

When there are shifts in the layout which require separate modules to work together in their design change, we use a common breakpoint (a major breakpoint). Perhaps you have a layout adjustment which moves a stacked list of products at small viewport widths to a two-column layout at larger viewport widths. In this case, you’ll want to keep track of where this layout shift happens because it’s likely that there are many other changes which need to occur at the same viewport width.

Most of the work we do has between three and six major breakpoints. These are often set as Sass variables in our workflow so that we can make changes to them later in one place. It’s also common for us to have a set of major breakpoints for major sections of a site. For example, we may have three major breakpoints in the header of our site and three completely different major breakpoints in the footer. This keeps our work modular and allows for these sections to evolve independently while still maintaining cohesion with the system as a whole.

Minor Breakpoints

When more subtle changes to type or spacing are needed, we can still use a media query to make these adjustments (a minor breakpoint). These are typically one-off style modifications for things like font size (to keep line length in check) or to increase spacing as the viewport width increases. These minor adjustments demonstrate a deep attention to detail that can really set your work apart.

Instead of using preprocessor variables for these, we typically just use hardcoded numbers. We have, on occasion, also used preprocessor calculations to keep these relative to a major breakpoint. For example, if we have a major breakpoint at 30em called $bp_header-show-nav, I might want to adjust the font size of a heading at 5em over the $bp_header-show-nav breakpoint. In this case, that would happen at 35em. Should we shift that major breakpoint to 32em at some point in the future, the minor change would then happen at 37em. Thinking relatively with minor breakpoints can help if you suspect that the major breakpoints might change. You’ll have to use your judgment on a case-by-case basis to make the best decisions.

Further Reading

For more on breakpoints, check out these articles:

- “There is no Breakpoint”

- “The In-Between” by Mark Boulton

- “Pragmatic Responsive Design” by Stephanie Rieger

Transitioning Out

These days, it’s not enough just to build great sites. We also have to consider the longevity of what we build. While approaches like atomic design can help, we need to do more. At the moment, most of our projects include some kind of training component — and I’m not talking about teaching the client to use the CMS. As organizations begin to truly understand the value the web offers them, they are deciding to build their own teams to own and maintain their web properties. If we want to build something that lasts, we need to make sure the team taking on our work is capable of properly maintaining it. For this reason, we’re doing much more in-depth training around the techniques we use to build for the web.

Fortunately, there are now many common ways to approach the transition. Every repo we create in source control has a useful readme file; we deliver automated tests supporting our code; and we’re working on some ways to transition the performance budget of a project so that our clients continue to maintain the speed of their sites. Along with atomic thinking, we also deliver working examples of subsystems we build. For example, it is common for us to consider how typography works across all web properties in the context of a customer’s brand, so we might also provide detailed documentation on this typographic system, as well as a page of examples showing how to use it. These kinds of additions to our work make for a much easier time as we pass the code from our team to our client’s team.

There are also deeper repercussions to all of this. Understanding who will maintain the system you’re building should also influence the decisions you make around technology choice and development technique. In other words, if your client’s web team is not ready to use Grunt with Assemble and a local server from the command line, you need to find a way to work that better matches their capabilities. Remember, you’re building this for them.

It has also been tremendously beneficial to invite our client’s web design and development teams to participate with us on the project. Using the project as an opportunity to train your client’s team demonstrates incredible value and makes you an easy choice among your competition.

People Over Process

One final thing I’ve learned in constantly evolving our workflow is that the process you choose to use is much less important than the people using it. If you want to build better web products, start by developing your people. This will get you further than any tweak to your process or workflow.

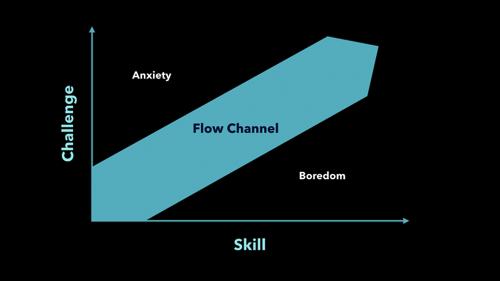

Keeping Your Team Happy

Along these same lines, I’d recommend reading Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. In this book, he explains the research he has done to better understand individual happiness. He describes what he calls the “flow channel,” charting skill level along the x-axis against challenge level along the y-axis. The flow channel is the area where your skill is met with an adequate challenge. Too much challenge for your skill creates anxiety and too little challenge for your skill results in boredom.

This can be translated to what we do by considering where we challenge ourselves in our day-to-day work. At Sparkbox, we talk about a culture of learning. That (hopefully) means the skill of my team is continually increasing. It follows, then, that to be happy we need to find continually increasing challenges to match our continually increasing skill. It’s our responsibility to balance this need for innovation with financial responsibility in the budgets our clients have.

This is tricky. For us, it’s meant we needed to stop reinventing the wheel; it’s led us to consider libraries of well-tested interface elements as opposed to repeatedly solving the same problems on every project. It’s meant we need to understand where each of our customers should spend money to innovate. And it has required quite a bit of transparency between those clients and our team so that we’re all on the same page.

In the end, it makes for a more content team — one that loves the work they do because it challenges them in just the right way. And it makes for a more content client — one that respects your recommendations about where and why they should invest. This is excellent for everyone involved.

Onward

This is the part where I deeply inspire you and encourage you to brave a bold new world of web design. But, to be honest, I’ve struggled to summarize a closing sentiment for this chapter.

After some contemplation, I believe this is because writing on process is never really done.

I hope that as you’ve read these words, you’ve found yourself more inspired to invest in your own understanding of how the web works, and more willing to invest in your teammates’ understanding. I hope you’ve felt excited to try a new approach, but I also hope you’ve felt empowered to tear these pages up if they don’t work for you. Only you, your team and your customer can figure out the best way to approach a project. This is the nature of what we do.

The time is now — so, get to it!

(og)

(og)

About The Book

Responsive design is a default these days, but we are all still figuring out just the right process and techniques to better craft responsive websites. That’s why we created Smashing Book 5 — to gather practical techniques and strategies from people who have learned how to get things done right, in actual projects with actual real-world challenges.

Just like all of our Smashing Books, the book isn’t concerned with trends or short-lived workarounds. It focuses on the actual design process — the why of the decisions we make as we craft websites. Think of it as a reliable playbook for issues that keep popping up in every responsive project — just the playbook you need to master all the tricky facets and hurdles of responsive design.

This book won’t solve every single issue in your responsive projects, but it will help you deal with common challenges effectively: be it front-end architecture, layout issues, resolution-independent assets, performance issues, responsive images or pretty much everything else related to responsive design. Shipping worldwide. Available as print and eBook.

Smashing Book #5 has completely changed the potential for books around the web. This thing is ridiculous in how it dives deep into a topic and continues to dive deeper until you feel as though your brain might explode from the knowledge.

—Paul Scrivens, “Smashing Book #5, A Review”

Smashing Book #5 is now your RWD bible. Stop searching, buy this book, and spend a weekend filling your brain with the most useful, technical information on RWD you can find anywhere.

And that’s what is most impressive to me about this book. It’s no different than sitting in a work environment with these authors and seeing how they get the job done. When you are trying to get into this field you are often left on your own to figure things out.

Table Of Contents of Smashing Book 5

We invited respected designers and developers who know a thing or two about responsive websites. The chapters have also been reviewed by active members of the community such as Jake Archibald, Dmitry Baranovsky—just to name a few.

| AUTHOR | CHAPTER | DETAILS |

|---|---|---|

| Vitaly Friedman | Preface | |

|

Summary • As designers and developers, we solve problems for a living. Yet, these problems are often quite tricky and complex, and the context of these problems requires us to be creative and flexible in our workflows. With responsive design, we are prompted to create scalable design systems that work well in unpredictable environments. To do that, we need to be pragmatic and find solutions that work well within given constraints. That’s why we created this book: to find techniques that have actually worked in real-life projects with real-world challenges. Keywords • design systems • scalability • bulletproof solutions • front-end techniques • real-world challenges |

||

| Daniel Mall | Responsive Designer’s Workflow | |

|

Summary • In practice, responsive projects usually require more time, more skills, more testing and hence more flexibility in budgets. Addings changes late delays projects immensely, and process involving designers, developers and clients is usually tiring to say the least. Keywords • responsive workflow • element collage • style tiles • tools • deliverables • performance budget • interface inventory • sketching • planning • manifestos • hypothesis • atomic design • designing in the browser • Photoshop |

||

| Vitaly Friedman | Responsive Design Patterns and Components | |

|

Summary • So, how do we deal with complex tables when building responsive websites? What about advanced interface components? Dashboards? What about the behaviour of web forms, navigation, mega-drop down menus, filters? Can we utilize vertical media queries and portrait/landscape orientation change? In this chapter, Vitaly will provide an overview of clever practical techniques for improving UX of responsive sites, with innovative approaches to designing "responsive modules" such as mega-drop downs, tables, calendars, accordions, maps, sliders, responsive PDF and responsive iconography — and a dash of anti-patterns to avoid as well. Keywords • design patterns • navigation • smart front-end techniques • priority+ pattern • improved off-canvas • lazy loading • autocomplete • filters • responsive PDF • portrait/landscape mode • sliders • country selector • responsive iconography. |

||

| Eileen Webb | Structured Content For RWD | |

|

Summary • Content created by one department is never updated by the next. Services get renamed in the navigation, but are still referenced by the old name in the body text. Important information is buried in the murky depths of flowery prose. Keywords • structured content • content consistency • content models • structural audit • editorial content • content types • content relationships • data-driven gaps • feature-driven gaps • authors and editors • CMS • content maintenance |

||

| Sara Soueidan | Mastering SVG For RWD And Beyond | |

|

Summary • This chapter has hands down on everything you need to know in order to start designing and building flexible components and visual assets with SVG. Sara will take you on a journey through SVG syntax, SVG accessibility, SVG viewport and viewBox, creating and exporting SVGs, embedding SVGs, building SVG sprites, creating SVG icon systems, using SVG Data URIs, optimizing SVG for performance, SVG conditional processing, clever SVG tricks and techniques and making SVG cross-browser responsive with CSS. Yep, everything you need to know about SVG, as promised. Keywords • SVG • syntax • accessibility • viewport • viewBox • exporting • embedding • sprites • icon systems • data URIs • performance • smart SVG techniques • responsive iconography • cross-browser fallbacks |

||

| Zoe M. Gillenwater | Building Responsive Components With Flexbox | |

|

Summary • We can use Flexbox for a while now. In fact, Flexbox solves a lot of CSS shortcomings and makes building responsive layouts much easier than with floats or positioning. It gives you more control over the things you care about in a responsive layout (such as order, alignment, and proportional sizes of your boxes) and lets the browser figure out the rest; the math-y stuff that computers are good at, like the exact dimensions that are needed on the boxes to perfectly fill the available space. Keywords • syntax variants • |

||

| Bram Stein | Web Fonts Performance | |

|

Summary • By default, web fonts block rendering, hiding content from the user. The only way to make content accessible as soon as possible is by treating web fonts as a progressive enhancement. This doesn’t mean web font performance is not an issue. You still need to load web fonts as quickly as possible so that users experience your site exactly how you designed and built it. Let's fix this. Keywords • font formats • font loading • font-rendering • FOIT and FOUT • Font Loading API • fallback fonts • inlining fonts • simulating swapping • promises • asynchronous loading and caching • prioritized loading |

||

| Yoav Weiss | Using Responsive Images, Today | |

|

Summary • So you want to serve different images to different screens. Perhaps a Retina image (only) to Retina screens, or an art-directed image to small screens, or a portrait image for portrait orientation, or perhaps .webp to browsers supporting the format — without performance hits. Since images are the heaviest assets on the web, dealing with them intelligently is both our responsibility and opportunity for more dynamic layouts. That's what native responsive images are for. Keywords • CSS pixel and DPR • Retina displays • fixed-width images • variable-width images • srcset and sizes • art direction • <picture> element • separation of concerns • image format fallback • accessibility • background images • image optimization • WebP and JPEG-XR • compressive images • deployment • common pitfalls |

||

| Fabio Carneiro | The Dark Side Of Responsive HTML Email | |

|