I recently migrated my blog from WordPress to Jekyll, a fantastic website generator that’s designed for building minimal, static blogs to be hosted on GitHub Pages. The simplicity of Jekyll’s theming layer and writing workflow is fantastic; however, setting up my website took a lot longer than expected.

What is Jekyll?

Jekyll is a website generator that’s designed for building minimal, static blogs to be hosted on GitHub Pages.

In this article we’ll walk through the following:

- the quickest way to set up a Jekyll powered blog;

- how to avoid common problems with using Jekyll;

- how to import your content from WordPress, use your own domain name, and blog in your favorite editor;

- how to theme in Jekyll, with Liquid templating examples;

- a couple of Jekyll 2.0’s new features, including Sass and CoffeeScript support and collections.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Content Modeling With Jekyll

- Static Website Generators Reviewed: Jekyll, Middleman, Roots, Hugo

- Why Static Website Generators Are The Next Big Thing

- A Simple Workflow From Development To Deployment

Jekyll’s Simple Purpose

Tom Preston-Werner created Jekyll to enable people to blog using a simple static HTML website, with all of the content hosted and version-controlled on GitHub. The goal was to eliminate the complexity of other blogging platforms by creating a workflow that allows you to blog like a hacker.

Jekyll takes your content written in Markdown, passes it through your templates and spits it out as a complete static website, ready to be served. GitHub Pages conveniently serves the website directly from your GitHub repository so that you don’t have to deal with any hosting.

Here are some websites that were created with Jekyll:

- Barry Clark’s blog (that’s me)

- Zach Holman’s blog

- CSS Wizardry

- Jekyll

- HealthCare.gov’s landing page and content subpages

- Development Seed

The Advantages of Going Static

- Simplicity. Jekyll strips everything down to the bare minimum, eliminating a lot of complexity:

- No database. Unlike WordPress and other content management systems (CMS), Jekyll doesn’t have a database. All posts and pages are converted to static HTML prior to publication. This is great for loading speed because no database calls are made when a page is loaded.

- No CMS. Simply write all of your content in Markdown, and Jekyll will run it through templates to generate your static website. GitHub can serve as a CMS if needed because you can edit content on it.

- Fast. Jekyll is fast because, being stripped down and without a database, you’re just serving up static pages. My base theme, Jekyll Now, makes only three HTTP requests — including the profile picture and social icons!

- Minimal. Your Jekyll website will include absolutely no functionality or features that you aren’t using.

- Design control. Spend less time wrestling with complex templates written by other people, and more time creating your own theme or customizing an uncomplicated base theme.

- Security. The vast majority of vulnerabilities that affect platforms like WordPress don’t exist because Jekyll has no CMS, database or PHP. So, you don’t have to spend as much time installing security updates.

- Convenient hosting. Convenient if you already use GitHub, that is. GitHub Pages will build and host your Jekyll website at no charge, while simultaneously handling version control.

Let’s Try It Out

There are multiple ways to get started with Jekyll, each with its own variations. Here are a few options:

- Install Jekyll locally via the command line, create a new boilerplate website using

jekyll new, build it locally withjekyll build, and then serve it. (The Jekyll website shows this workflow.) - Clone a starting point to your local machine, install Jekyll locally via the command line, make updates to your website, build it locally, and then serve it.

- Fork a starting point, make changes, and then serve it.

We’ll get started with the quickest and easiest option: forking a starting point. This will get us up and running in a few minutes, and we won’t have to install any dependancies. Here’s what we’re going to do directly on GitHub.com in the browser:

- Create our Jekyll powered website.

- Host it for free on GitHub Pages.

- Customize it to include our name, avatar and social links.

- Publish our first blog post!

1. Fork A Starting Point

We’ll start by forking a repository that has followed best practices and the workflows that we’ll be covering in this article. This will get us on the right track and save a lot of time.

I have prepared a repository for us already. Head to Jekyll Now, and hit the “Fork” button in the top-right corner of the repository to fork a copy of the blog theme to your GitHub account.

Starting with a fork is great because it will give you a feel for what Jekyll is like before you have to set up a local development environment, install dependencies and figure out Jekyll’s build process.

Common problem #1: Creating a Jekyll website through the local command line can be frustrating and time-consuming because you have to install and configure dependencies like Ruby and RubyGems. Let GitHub Pages build the website for you, until you have a real need to build it locally.

2. Host On Your GitHub Account

As a GitHub user, you’re entitled to one free “user” website (as opposed to a “project” website), which will live at http://yourusername.github.io. This space is ideal for hosting a Jekyll blog!

The best part is that you can simply place your unbuilt Jekyll blog on the master branch of your user repository, and GitHub Pages will build the static website and serve it for you. You don’t have to worry about the build process at all — it’s all taken care of.

Click the “Settings” button in your new forked repository (in the menu on the right), and change the repository’s name to yourusername.github.io, replacing yourusername with your GitHub user name.

Your website will probably go live immediately. You can check by going to http://yourusername.github.io. Don’t worry if it isn’t live yet: Step 3 will force it to be built.

Whew! We’re moving fast here. We already have a Jekyll website up and running! Let’s step back for a second and look at some of the most common issues to be aware of when hosting a Jekyll website on GitHub Pages.

Common problem #2: Be aware of the difference between user websites and project websites on GitHub. With a user website (which we’re setting up), you don’t need to do any branching. The master branch is already configured to run anything placed on it through Jekyll. You don’t need to set up a gh-pages branch.

Common problem #3: Using a project website for your Jekyll website introduces some complexity because your website will be published to a subdirectory. The URL will look like http://yourname.github.io/repository-name, which will cause problems in Jekyll templates, such as breaking references to images and not letting you preview the website locally.

Common problem #4: Jekyll has a lot of plugins, but GitHub Pages supports only a few of them. If you try to include a plugin that isn’t supported, then Jekyll will fail while building your website. So, stick to the supported list. Luckily, my favorite plugin is on the list: Jemoji lets you include emoji in blog posts, just like you would on GitHub and Basecamp.

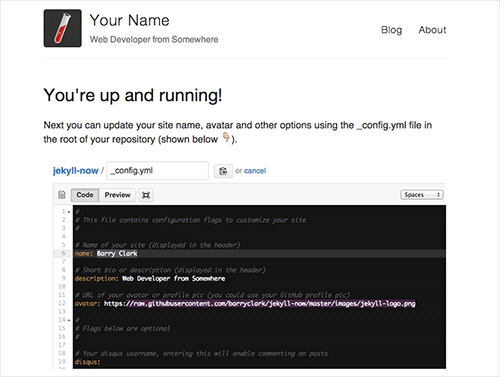

3. Customize Your Website

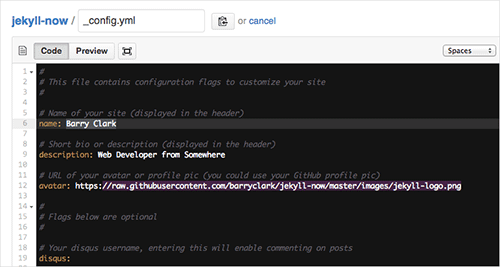

You can now change your website’s name, description, avatar and other options by editing the _config.yml file. These custom variables have been set up for convenience and are pulled into your theme when your website gets built.

Making a change to _config.yml (or any file in your repository) will force GitHub Pages to rebuild your website with Jekyll. The rebuilt website will be viewable a few seconds later at http://yourusername.github.io. If your website wasn’t live immediately after step 2, it will be after this step.

Go ahead and customize your website by updating the variables in your _config.yml file and then committing the changes.

You can change your blog’s files from here on in one of three ways. Pick whichever suits you best:

- Edit files in your new

username.github.iorepository directly in the browser at GitHub.com (as shown below). - Use a third-party GitHub content editor, such as Prose by Development Seed. It’s optimized for Jekyll, which makes it easy to edit Markdown, write drafts and upload images.

- Clone your repository and make updates locally, and then push them to your GitHub repository (Atlassian has a guide on this).

_config.yml on GitHub.com. (Image credit: Jekyll Now) (View large version)Common problem #5: Don’t assume that you need to jekyll build the website locally in order to customize and theme a Jekyll website. GitHub Pages does that for you. You just need to place the files that you want to be built in the master branch of your user repository or in the gh-pages branch of any other repository, and then GitHub Pages will process it with Jekyll.

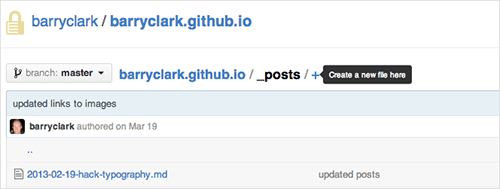

4. Publish Your First Blog Post

Your website is now customized, live and looking good. You just have to publish your first blog post:

- Edit

/_posts/2014-3-3-Hello-World.md, deleting the placeholder content and entering your own. If you need a quick primer on writing in Markdown, check out Adam Pritchard’s cheat sheet. - Change the file name to include today’s date and the title of your post. Jekyll requires posts to be named

year-month-day-title.md. - Update the title at the top of the Markdown file. Those variables at the top of the blog post are called front matter, which we’ll dig into a little later. In this case, they specify which layout to use and the title of the blog post. Additional front-matter variables exist, such as

permalink,tagsandcategory.

If you’d like to create new blog posts in the browser on GitHub.com, simply hit the “+” icon in /_posts/. Just remember to format the file name correctly and to include the front-matter block so that the file gets processed by Jekyll.

Common problem #6: One concern I had about using Jekyll for my blog was that it has no CMS, so I wouldn’t have the convenience of being able to make quick edits by logging into a CMS interface when I’m away from my laptop. It turns out that your Jekyll blog will have a CMS if you use GitHub Pages, because GitHub itself serves as the CMS. You can edit posts in the browser, even on your phone if you wish. It might not be as convenient as other CMS’, but you won’t be stuck when you’re away from your computer and need to make a change.

Optional Steps

Use Your Own Domain

Configuring your domain name to point to GitHub Pages is a simple two-step process:

- Go to the root of your blog’s repository, and edit the CNAME file to include your domain name (for example,

www.yourdomainname.com). - Go to your domain name registrar, and add a CNAME DNS record pointing your domain to GitHub Pages:

- type:

CNAME - host:

www.yourdomainname.com - answer:

yourusername.github.io - TTL:

300

- type:

Then, refresh What’s My DNS like crazy until you’ve propagated. If you run into any problems, refer to “Setting Up a Custom Domain With GitHub Pages.”

Import Your Blog Posts From WordPress

Before importing, you’ll need to export your data from WordPress, possibly massaging the data a little (for example, by updating the image references), and then import it into your new Jekyll website. Fortunately, a few great tools can help.

To export from WordPress, I’d highly recommend Ben Balter’s one-click WordPress to Jekyll Exporter plugin. It exports all of your WordPress content as a ZIP file, including posts, images and meta data, converting it to Jekyll’s format where needed. Good on you, Ben.

The other option is to export all content in the “Tools” menu of the WordPress dashboard, and then importing it with Jekyll’s importer.

Next, we need to update our image references. Ben Balter’s plugin will export all of your images into a folder. Then, you’ll need to copy them to wherever you’re hosting your images on your Jekyll blog. This could be in an /images folder or on a content delivery network.

Then, you have the fun task of updating all of the links to these images across your WordPress content. Because I was only updating five or six posts, a quick find-and-replace worked well, but if you have a lot of content, then it might be worth writing a script or checking out scripts that others have written, such as Paul Stamatiou’s.

Finally, we have to import comments. Being a platform for static websites, Jekyll doesn’t support comments. However, a hosted solution like Disqus works really well! I’d recommend importing your WordPress comments to Disqus. Then, if you’re using Jekyll Now, you can enter your Disqus user name in _config.yml and you’re set.

Blog Locally in Your Favorite Editor

If you prefer to write in Sublime, Vim, Atom or another editor, all you need to do is clone to your repository, create new Markdown blog posts in the _posts folder, and then push the changes to GitHub. GitHub Pages will automatically rebuild your website as soon as your Markdown file hits the repository, and your new blog post will be live as soon as the build is complete.

- First,

git clone git@github.com:yourusername/yourusername.github.io.git, or clone your repository using GitHub Mac. - Create a new post in the

_postsfolder. Remember to name it in the formatyear-month-day-title.md, and include the front matter at the top of the post. - Commit the post’s Markdown file, and push to your GitHub repository. (Atlassian’s guide to Git’s basics might come in handy.)

- That’s it! Just wait for GitHub Pages to rebuild your website. This typically takes under 10 seconds, assuming you don’t have a huge amount of content.

Common problem #7: Again, you don’t need to build your Jekyll website locally in order to write a blog post locally and publish it to your website. You can write the Markdown post locally and push it with any images you’ve used, and then GitHub Pages will rebuild the website for you on the server.

Theming In Jekyll

Want to customize your theme? Here are some things you should know.

Building Your Website Locally

If your theme development is more substantial, then building and testing your Jekyll website locally could be convenient. This step isn’t required for theme development. You could just push the theme changes to your repository, and GitHub Pages will do the build for you. However, having Jekyll watch for theme changes locally and preview the website for you would be helpful if you’re creating a custom theme.

First, you’ll need to install Jekyll. The easiest way to do this is to install the GitHub Pages gem by running gem install github-pages. It’ll keep your local environment in sync with the same versions of all of the gems that are used to build GitHub Pages, and includes Jekyll and all of the dependancies you’ll need, like: kramdown, jemoji, and jekyll-sitemap. You will need to have Ruby ~> 1.9.3 and RubyGems installed.

Here is the workflow for building and viewing your Jekyll website locally:

- First,

cdinto the folder where your Jekyll website is stored. - Then,

jekyll serve --watch. (Jekyll explains more build options.) - View your website at

http://0.0.0.0:4000. - When you’re done, commit the changes and push everything to the master branch of your GitHub user website. GitHub Pages will then rebuild and serve the website.

Common problem #8: Keep in mind that jekyll build will wipe everything in /_sites/. The first step of jekyll build is to delete everything in /_sites/ and then build it all again from scratch. So, you can’t store any files in there and expect them to stick around. Everything that goes into /_sites/ should be generated by Jekyll.

Directory Structure

Here’s a snapshot of my Jekyll website’s directory structure:

/Users/barryclark/Code/jekyll-now

├─ CNAME # Contains your custom domain name (optional)

├─ _config.yml # Jekyll's configuration flags

├─ _includes # Snippets of code that can be used throughout your templates

│ ├─ analytics.html

│ └─ disqus.html

├─ _layouts

│ ├─ default.html # The main template. Includes <head>, <navigation>, <footer>, etc

│ ├─ page.html # Static page layout

│ └─ post.html # Blog post layout

├─ _posts # All posts go in this directory!

│ └─ 2014-3-3-Hello-World.md

├─ _site # After Jekyll builds the website, it puts the static HTML output here. This is what's served!

│ ├─ CNAME

│ ├─ LICENSE

│ ├─ about.html

│ ├─ feed.xml

│ ├─ index.html

│ ├─ sitemap.xml

│ └─ style.css

├─ about.md # A static "About" page that I created.

├─ feed.xml # Powers the RSS feed

├─ images # All of my images are stored here.

│ ├── first-post.jpg

├─ index.html # Home page layout

├─ scss # The Sass style sheets for my website

│ ├─ _highlights.scss

│ ├─ _reset.scss

│ ├─ _variables.scss

│ └─ style.scss

└── sitemap.xml # Site map for the website

Liquid Templating

Jekyll uses the Liquid templating language to process templates. There are two important things to know about using Liquid.

First, a YAML front-matter block is at the beginning of every content file. It specifies the layout of the page and other variables, like title, date and tags. It may include custom page variables that you’ve created, too.

Liquid template tags are used to execute loops and conditional statements and to output content.

For example, each blog post uses the following layout from /_layouts/post.html:

---

layout: default

---

<article class="post">

<h1>{{ page.title }}</h1>

<div class="entry">

{{ content }}

</div>

<div class="date">

Written on {{ page.date | date: "%B %e, %Y" }}

</div>

<div class="comments">

{% include disqus.html disqus_identifier=page.disqus_identifier %}

</div>

</article>

At the top of the file, YAML front matter is surrounded by triple hyphens. Here, we’re specifying that this file should be processed as the content for the default.html layout, which contains the website’s header and footer.

Liquid markup uses double curly braces to output content. The first Liquid template tags that do this in the example above are {{ page.title }} and {{ content }}, which output the title and content of the blog post. A number of Jekyll variables are made available for outputting in templates.

Single curly braces and modules are used for conditionals and loops and for displaying includes. Here, I’m including a Disqus commenting partial at the bottom of the blog post, which will display the markup from /_includes/disqus.html.

_config.yml

This is Jekyll’s configuration file, containing all of the settings for your Jekyll website. The great thing about _config.yml is that you can also specify all of your own variables here to be pulled in via template files across the website.

For example, I use custom variables in Jekyll Now’s _config.yml to allow SVG icons to be easily included in the footer:

Here is _config.yml:

# Includes an icon in the footer for each user name you enter

footer-links:

github: barryclark

twitter: baznyc

And here is /_layouts/default.html:

<footer class="footer">

{% if site.footer-links.github %}<a href="http://github.com/{{ site.footer-links.github }}">{% include svg-icons/github.html %}</a>{% endif %}

{% if site.footer-links.twitter %}<a href="http://twitter.com/{{ site.footer-links.twitter }}">{% include svg-icons/twitter.html %}</a>{% endif %}

</footer>

The variable is outputted to the Twitter URL like this: http://twitter.com/{{ site.footer-links.twitter }}, so that the footer icon links to your Twitter profile. One other thing I really like about variables is that you can use them to optionally add pieces of UI. So, a footer icon wouldn’t be displayed if you don’t enter anything in the variable.

Common problem #9: Note that _config.yml changes are loaded at compile time, not runtime. This means that if you’re running jekyll serve locally and you edit _config.yml, then changes to it won’t be detected. You’ll need to kill and rerun jekyll serve.

Layouts and Static Pages

Most simple blog websites need only two layout files: one for blog posts (post.html) and one for static pages (page.html). The only real difference between these in Jekyll Now is that post.html includes the Disqus comments block and a date, and page.html doesn’t.

If you create a file with an .html or .md extension in the root of your Jekyll website, it will be treated as a static page. For example, about.md would be outputted as www.mysite.com/about. Nice and easy!

Images

I store my images in an /images/ folder in the repository and haven’t had any performance problems yet. If your website is hosted on GitHub Pages, then the images will be served up by GitHub’s super-fast content delivery network. I haven’t found the need to store them elsewhere yet, but if I wanted to migrate my images to somewhere like CloudFront, then just pointing all of my image links to a folder on that server would be easy enough.

I like the simplicity of saving an image to the /images/ folder and then linking to it in the content. The Markdown to include an image in content is simple:

Preprocessor Support

Jekyll now supports Sass and CoffeeScript without any need for plugins or Grunt files. You can include your .sass, .scss and .coffee files anywhere in your website’s directory, and Jekyll will process it, outputting a .css file in that same directory.

To ensure that your .sass, .scss and .coffee files get processed, start the file with two lines of triple hyphens, like this:

---

---

$color-coffee: #644C37;

If you’re using @imports to break out your Sass into partials, then you’ll need to let Jekyll know that by including the following flag in your _config.yml file.

sass:

sass_dir: _scss

You can specify the outputted style here, too:

sass:

sass_dir: _scss

style: :compressed

Advanced Jekyll Features

Jekyll has a couple of powerful, more advanced features that might help you if you’re looking to scale up your website from a simple blog.

Data Files

There are two ways to integrate external data with a Jekyll website. The first is by using third-party services and APIs. For example, Disqus allows you to embed dynamic content on your static website via its external service.

The second way is by using data files. Jekyll is able to read YAML and JSON data files from the /_data/ folder, allowing you to use them in your templates just like other variables. This is really useful for storing repetitive or website-specific data that you wouldn’t want bulking up _config.yml.

Data files also make it possible to include large data sets in your Jekyll website. You could write a script to break down a big data set into JSON files and place them in your Jekyll website’s /_data/ folder. A creative example of this is serving Google Analytics data to Jekyll in order to rank blog posts by popularity.

Collections

The two standard document types in Jekyll are posts (for blog content) and pages (for static pages). The launch of Jekyll 2.0 brought collections, which allow you to define your own document types. For example, you could use a collection to define a photo album, book or portfolio.

Conclusion

Jekyll isn’t for every project. The biggest disadvantage of a static website generator is that incorporating dynamic server-side functionality becomes difficult. The number of services to integrate, like Disqus, is growing, but not all offer much flexibility or control. Jekyll isn’t suited to building user-based websites because there is no database or server-side logic to handle user registration or logging in.

Jekyll’s strength is its simplicity and minimalism, giving you just what you need to create a content-focused website that doesn’t need much dynamic user interaction — and no more. This makes it perfect for your blog and portfolio and also worth considering for a simple client website.

Don’t let Jekyll’s reputation as a blogging platform for hackers dissuade you. Building a beautiful, fast, minimal website in Jekyll doesn’t require elite hacker skills or knowledge of the command line. As shown in the walkthrough, you can get set up in a matter of minutes, giving you more time to spend on your content and design.

Further Resources

- Jekyll The official website is the best resource for theming Jekyll and creating a website. A lot of the information in this article was drawn from it.

- Jekyll Now This starting point makes it easier to create a Jekyll blog by eliminating a lot of the up-front setting up.

- Jekyll source code The Jekyll repository shares the source code and discussions about Jekyll.

(al, ml)

(al, ml)