No person is immune from the influence of the people and groups they encounter. As much as we would like to think that every thought we have is original, that every opinion we express is informed by facts alone, the truth is that we use others around us as a reference point for much of our attitudes and behavior. This isn’t a bad thing; it’s human nature.

Knowing how groups influence people can help you to move from being a common, everyday, work-your-fingers-to-the-bone designer to a strategic influencer of your target audience with relative ease. In fact, whether researchers, designers or managers, everyone involved in user experience (UX) design would benefit from deeper knowledge of how to incorporate social influence in their work.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Think Fast! Using Heuristics To Increase Use Of Your Product

- The User Is The Anonymous Web Designer

- Beyond Usability: Designing With Persuasive Patterns

- Designing For A Hierarchy Of Needs

In this article, we’ll focus on how concepts related to social identity theory — a theory within the psychology field of social influence — can help UX professionals to more effectively incorporate social influence in their work.

Social Identity: Old Theory, New Application

Way back in the day (1979, to be exact), Henri Tajfel published a chapter (PDF) arguing that, in many situations in life, an individual acts not as an individual, but as a member of a group they identify with. Think of someone who identifies with a certain political party but is not well informed on the candidates or issues they are voting on. When they step into the voting booth, they vote down the party line solely because they identify with the values and beliefs of that particular party.

According to social identity theory, one implication of identifying with a particular group is that the closer that individuals feel to a group (the “in-group”), the more uniform their behavior will be and the more likely they will regard members of other groups (“out-groups”) as being cut from the same cloth, ascribing negative attributes to those out-groups.

Example: PC vs. Mac

Let’s look at an example from the Apple commercials of not so long ago. According to Apple, those who use Mac products are cool, edgy and hip. Members of this group would identify themselves as possessing those traits and would identify those who use Windows-based PCs as being uptight, stuffy and behind the times. Apple hoped that viewers would buy into these associations with Windows PC users. Thus, not wanting to identify with a group considered stuffy and boring, some individuals would want to purchase a Mac product. Apple used social identity in an attempt to cultivate an attitude towards its product that would lead to a certain behavior (in this case, purchasing a Mac product).

How Is Social Identity Developed?

An individual forms and reinforces their social identity through two key processes:

- Self-categorization. This refers to how an individual assigns themselves and others to categories based on beliefs, behavior, attitudes and other characteristics. To continue our example, “I think like a hip, trendy person” would be in line with being a Mac user, and “You think like a closed-minded, stuffy person” would be a trait of a Windows PC user.

- Social comparison. This refers to the process of comparing others to oneself and labelling their traits as being like (in-group) or unlike (out-group) your own, often associating positive or negative attributes with the group. For example, “Mac users wear skinny jeans and don’t tuck in their shirt,” which is seen as desirable, while “Windows PC users wear suits,” which isn’t desirable.

Of course, most people are members of multiple groups. This can complicate things. Also, social identity does not completely determine an individual’s attitudes and behavior. Applying social identity theory will increase your influence on users but will not guarantee its success. Many other factors influence a person’s decisions, including the persuasiveness of a design. Nevertheless, applying social identity theory could lead you to greater results, with less expenditure of resources.

Let’s look at how social identity theory plays out on the web.

A Social Identity UX Case Study: Facebook

Love it or hate it, Facebook is king of social networking for a reason. Social influence and social identity concepts have been successfully incorporated in the network.

Facebook’s Use of Self-Categorization: In-Group

Creating a profile on Facebook is an initial step in joining a group — you are now a part of Facebook, the group. And what typically causes someone to join Facebook? The reason is that they want to belong to social groups that reside on Facebook (an example of self-categorization), and they want others to see what they are doing and vice versa (social comparison). Members of Facebook already have these social characteristics in common.

An individual who creates a profile on Facebook is limited only by how they choose to self-categorize. Other people can then view the following:

- photos they’ve posted,

- jobs they’ve worked at,

- sports teams they like,

- books they’ve read,

- events they’ve attended,

- groups they belong to.

You can customize your profile to identify with social groups that you align with and to allow others to easily find out whether they would connect with you over certain things, thus enhancing your in-group ties.

How Social Identity Might Play Out on Facebook

Imagine that I posted a comment sharing my view that the US men’s soccer team is superior to Brazil’s national team (delusional, yes, but please work with me). One of my current friends likes my comment. This friend’s “like” shows up in the newsfeed of one of their friends, Jim, who lives in Philadelphia and is an avid US fan. Jim sees the comment and clicks on the link to my profile. Perusing my profile, which is configured to be accessible to friends of friends (they’re in-group, too, you know), Jim sees that I live in Philadelphia and am a fan of his favorite band, Sleigh Bells.

Jim sends me a request for friendship over Facebook. In response to his request, I check out his profile and see that he has similar interests, lives in my city and is friends (at least on Facebook) with similar people. I accept his friend request. We have just strengthened our social tie, reaffirmed our in-group identity with each other and discovered reasons to be active users of Facebook. The scenario could play out in many ways from here, including actually meeting with Jim and finding additional common interests and friends.

What Does Facebook Get Out of Facilitating Social Transactions?

You might be thinking, “But these are all feel-good things — people aren’t paying to be users of Facebook.” True, but we wouldn’t have to look far to see that social identity and influence have benefited entrepreneurs in social media. Additionally, Facebook tracks people’s exchange of data in ways we can only imagine, primarily to surface advertising and other promotions. Perhaps Jim and I are now on Facebook’s list of Philadelphia residents who are fans of US soccer. Perhaps we’ll both start to see paid advertisements in our feed from local venues that host soccer-viewing parties. That’s a win for Facebook, a win for advertisers and a win for Jim and me (but mostly Jim).

Add to this the other social transactions that users can make over Facebook:

- post pictures and tag friends,

- comment on what others have posted,

- create groups,

- suggest that other friends join groups and like pages.

You can see how Facebook has used the principles of social identity theory (perhaps inadvertently) to become the biggest player in social media.

There’s more.

Facebook’s Use of Social Comparison: Out-Group

Facebook facilitates out-group interactions as well. Remember that identifying those not like you reinforces your identity just as much.

Let’s say that Jim from our previous example checks out another person’s profile and finds that they belong to the animal rights group PETA. The person has posted a few comments pointing out the rights of animals. (Please note that this is merely an example to explain out-groups in the context of social identity. I do not have an affiliation with any of the groups mentioned here. Eat meat or don’t — it’s your choice.)

As an avid hunter and wearer of fine furs, Jim sees this as being out of line with his social identity (making the other person part of an out-group), and perhaps he ascribes negative characteristics or traits to this person that he identifies as belonging to all PETA members (for example, dismissing him as a “vegan nut case”). Being motivated to counter PETA’s viewpoint, Jim searches Facebook for anti-PETA groups to join. He finds and likes Hunters Against PETA, where he is able to socialize with like-minded peers.

Once he is comfortable with the group, Jim comes back and posts the comment shown below, based on a recent run-in he had with PETA folks on a university campus. Note the language he uses to lump all PETA members as “freakin’ psychos,” a clear out-group generalization. Jim doesn’t know many, perhaps any, PETA members well enough to classify them as “psychos.” While he’s on the page, Jim links to the profile of another group member and sees that they share 26 friends. Jim sends this member a friend request. Jim’s ties with Facebook and Hunters Against PETA have now been strengthened through social comparison.

Why Would Facebook Want to Facilitate Out-Group Interactions?

As with positive in-group interaction, Jim is now a stronger member of the Facebook community, and Facebook has recorded his interests and interactions for future marketing campaigns. Jim might not receive any further ads for campaigns to raise money or awareness for animal rights, and he might see more ads about local gun shows, concealed carry classes and any other interests that fellow members of Hunters Against PETA have been found to share. Jim might also use Facebook more, knowing he can find like-minded individuals who are against the same groups he is against.

How Non-Social Media Websites Incorporate Social Identity Theory

Not that this is rocket science, but if you don’t thoughtfully incorporate elements of social identity theory to address social influence, then you run the risk of, first, doing it wrong or poorly and, secondly, missing out on opportunities to influence users that your competitors will take advantage of. This goes beyond e-commerce websites. Pew reports that people have looked to the Internet for years to facilitate their group connections and further the causes of their groups. While I cannot speak to the financial effectiveness of the examples below, the companies do demonstrate how to incorporate social influence into design, thereby increasing the appeal and effectiveness of their products.

The Columbus Dispatch

Email and social media are common platforms through which in-groups share articles from online news outlets. The Columbus Dispatch, like many online news outlets, enables individuals to easily share noteworthy articles through email and popular social networks. Not only does this heighten the knowledge of and interest in the topic among the group, but it tells members that the group as a whole considers The Columbus Dispatch to be a trustworthy source of news. The news outlet benefits from increased traffic, trust and visibility among members.

The strategy can backfire. By displaying the number of shares, The Dispatch also tells users which articles are not popular. A lack of sharing might deter some users if they think an article would not be popular among their group.

Kiva

Kiva, a platform that helps individual lenders make micro-loans by connecting them to micro-finance institutions around the world, uses both self-categorization and social comparison to promote lending. Individuals can join a team that aligns with a group they feel connected to (self-categorization) and compare what people in out-groups are lending (social comparison). Theoretically, this should create competition between unlike groups, raising more money overall for micro-finance institutions to give to borrowers. It is probably not a coincidence that the default view of the group listing (shown below) shows an atheist group immediately followed by a Christian group (the top two contributing groups in cumulative dollars). The right panel of the screen displays a leaderboard, highlighting which groups are raising the most funds recently.

Again, this strategy could backfire. If a prospective member sees that a group is struggling to raise funds, ideally they would be inspired to join that group, lend more money and recruit others to contribute. However, if they believe that any effort they expend to push the group ahead of the pack would be fruitless, then they might contribute to the group but not join or might find another venue in which to contribute.

Similarly, if a prospective contributor saw that a group has not had any recent activity, they might choose not to join the group or not contribute.

Amazon

Mega-retailer Amazon doesn’t shy away from wielding social influence. Individuals can share what they have purchased on a variety of popular social media platforms. A quick update on Facebook that you have found a good deal could net quite a few more sales over time from others in your group. Showing others your similar taste in products (social comparison) or emulating the shopping habits of people you identify with (in-group) is as simple as clicking a mouse.

The potential flaw in this design is that completely bypassing this form of social influence is as simple as not clicking a button. The questions and reviews sections for products allow for more robust social exchange, where conversation is generated that can truly influence purchasing decisions.

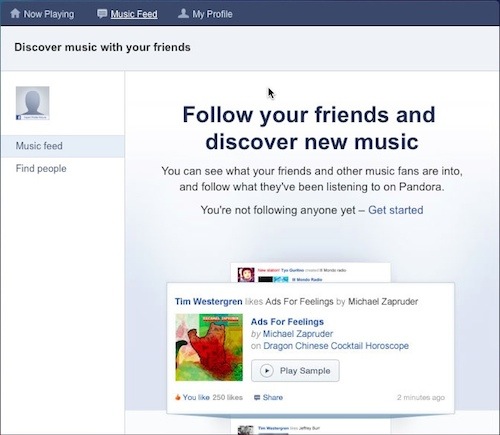

Pandora

Pandora is a platform on which users explore music, create channels based on interests (self-categorization), share those channels (in-group) and browse channels created by others (social comparison). Users can find who among their friends have shared music channels by logging in through Facebook. Additionally, users can choose whether to share their channels, sparing them any embarrassment if they happen to be a fan of music that some in their social circles would consider to be out-group.

Nike+

Nike+ connects members to a social network of peers who offer motivation, challenges and advice on running. Nike+ highlights the large number of individuals in its community on its landing page (shown below). Users also see Facebook friends who are members of the website. That’s enough to convince most people that they will find a likeminded individual or two with whom to form a group once they register.

If a new member realizes that those they consider in-group are running more than they are, perhaps they will increase their monthly regimen to be more in line with their in-group. Running can also be facilitated by social comparison; if they think running conflicts with what an out-group would do, an individual might consider joining an in-group that defines themselves as runners and might log their runs on Nike+.

Why does Nike care? More running means more products to be sold — oh, and a network of millions to collect data from and advertise products to.

Mendeley

Mendeley extends social identity to academic journals. Much of what becomes popular in academic theory and literature happens because academics share work that they respect with other academics (in-group sharing). With Mendeley, you can find groups based on common subjects of interest (self-categorization) and see what others in these groups are reading and sharing (in-group and social comparison).

Leveraging social comparison, Mendeley enables members to see which articles are being posted, who has posted which articles and how many other users have read a particular article. These types of statistics are very influential with academics, who need to stay current on literature considered relevant in their field. Mendeley allows for self-categorization by showing individuals what others are reading and allows for social comparison by showing what groups others belong to.

What Not to Do: Social Grocery

Social Grocery provides evidence that making something social and incorporating the tenants of social identity theory don’t necessarily mean that the venture will be a success. Moreover, calling something social doesn’t make it so. I can’t speak to the financial state of Social Grocery, but its website and social media efforts indicate that it is not currently facilitating social interactions effectively.

The company attempts to apply social identity theory by enabling individuals to publicly post grocery items that they like or dislike, make comments about those items (self-categorization), see what others in their social networks have posted and reviewed (social comparison) and earn points to increase their status in the group. Part of the trouble, as we saw with The Columbus Dispatch, is the lack of posts and diversity of participation. A look at Social Grocery’s landing page shows a three-day gap between posts (assuming that all posts are displayed chronologically), and of the three most recent posts, only one person decided to “like” something that someone else had posted. The lack of comments makes the experience void of meaningful social interaction over the five-day period covered by the three posts.

A number of additional problems exist.

Social Grocery seems to have abandoned its attempt to create a deep social network. The screenshot above shows that a few people still actively use the website. However, a quick jump to the company’s Twitter feed (below), which is directly linked to from the home page, shows that it has not tweeted since November (presumably 2013 but perhaps even one of the years prior). Prior to those November 4th tweets, the next tweets are from April 2012. “Social” Grocery? It doesn’t seem so.

Social Grocery’s Facebook page (below) has over 3,000 likes — not bad, much more than the number of friends I have. However, they have not posted anything for approximately two years. While Facebook asks me to invite my friends to like this page, I would be embarrassed if my friends thought I wanted them to be associated with this page (they might invite me to become a member of an out-group in response!).

The takeaway is that Social Grocery is about two years delinquent in implementing Kevin Stone’s advice on how to shut down a failing product in a dignified way. I wonder who the few stray users of this product are and what benefit they get from continuing to post on the website.

From a quick look through Social Grocery, a user might determine that it is an out-group and that people like them just wouldn’t use it.

How Can Social Identity Theory Work For You?

The examples above provide food for thought on how you might incorporate some of the tenants of social identity theory to influence your users. Much of what has been done is fairly intuitive, especially since the boom in social media, an era in which users assume that they will be able to interact with your product socially. So, what can you do to incorporate social identity into your product?

Ask Questions

In all of this, don’t lose sight of your audience. User research is critical to successfully implementing any social identity strategy. Answer the following questions before implementing it in your design:

- How do your users engage with your product outside of the digital realm?

- What common experiences with your product do users share?

- Are there drastic differences in lifestyle between your user types?

- How do competitors engage socially with their users? Are their efforts successful?

- Where is the low-hanging fruit? What ready-made social experiences can you drop into your design in order to hit the ground running?

- Are you committed to supporting the social interactions around your product for an indefinite period of time while it grows?

- Does incorporating social elements into your product even make sense? (If you’re selling groceries, then perhaps not.)

- Perhaps most importantly, how will you convey to users the opportunities to interact socially around your product?

- Being able to communicate effectively with your audience is a prerequisite to applying any social psychology principle. You don’t want to send mixed messages that lead people to feel that only an out-group would use your product.

Analyze the Opportunities

If you haven’t done so yet, take a closer look at what you offer and how it could be enhanced by social identity theory. Are there opportunities for individuals to connect around your product? It could be as simple as emulating Amazon by enabling users to share their purchases with friends.

Do you have any venues for groups of people to discuss your product, share transactions and make recommendations? Can you capitalize on in-group thinking by showing who else uses your product and providing testimonials? Nike+ has a more robust implementation than most would consider necessary, and based on the size of its community, its attempt to gamify running has proven to be successful.

Can you create competition by showing how use of your product would differentiate in-group members from those they consider out-group. If you framed it right, you could play both sides of the coin? Like Kiva, could you develop some healthy competition between groups to see who can be the top user of your product?

Social Grocery demonstrates the importance of committing to your social networks. “Seeding” social interaction is critical for any website whose owner aspires to incorporate the principles we’ve looked at. It doesn’t take much effort; you don’t have to reinvent the wheel, because Facebook, Twitter and other social networks already provide the framework. Enabling users to link to your product through existing networks is a shortcut to facilitating social interactions on your website.

You don’t need to do everything with social identity, but do be aware of your options and the level of effort required to implement them. If you are just starting to incorporate social concepts into your product, then you’ll need to develop a network quickly or rely on an existing network to inspire others to use your product. You need to commit to maintaining the network or else users will not stick around for the long haul.

Additionally, to apply social identity theory, you’ll need to highlight how use of your product would make someone more similar to an in-group or less similar to an out-group. And, importantly, you’ll need to commit the time, effort and resources to develop and implement the methods of social influence that you’ve chosen. Doing this while following the principles of social identity theory in your design will improve the experience of using your product, increase conversions and command greater respect for you in the market.

Summary

Social influence, particularly social identity theory, provides key concepts for you to address through UX design. You can influence people by thoughtfully incorporating social identity concepts into your design. Knowing the theory and how it plays out in real life will enable you to discuss with colleagues and potential clients how and why your design will be effective at influencing users.

Incorporating these concepts into your design will cover areas that many of your competitors would otherwise have taken advantage of and will position you as a designer of influence among your users and peers.

Additional Resources

Designing around social identity is a complex process. Here are some additional resources to help you along the way:

- “Reach Your Customers While Social Media Peaks,” Tessa Wegert, ClickZ

- “How to Make Your Website as Social as Your Customers,” David Williams, Forbes

- “Designing for Social Interaction: Strong, Weak, and Temporary Ties,” Paul Adams, Boxes and Arrows

(al, ml)

(al, ml)