Setting up JavaScript-based functionality to work across multiple devices can be tricky. When is the right time to load which script? Do your media queries matches tests, your geolocation popups tests and your viewport orientation tests provide the best possible results for your website? ConditionerJS will help you combine all of this contextual information to pinpoint the right moment to load the functionality you need.

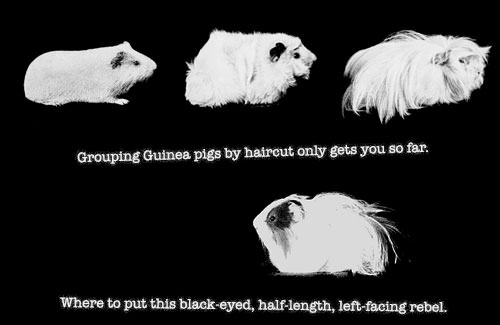

As you can clearly see, applying conditioner to guinea pigs results in very smooth fur. Take a moment and imagine what this could mean for your codebase.

Before we jump into the ConditionerJS demo, let’s quickly take a look at the Web and how it’s changing, because it’s this change that drove the development of ConditionerJS in the first place. In the meantime, think of it as a shampoo but also as an orchestra conductor; instead of giving cues to musicians, ConditionerJS tells your JavaScript when to act up and when to tune down a bit.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- A Beginner’s Guide To Progressive Web Apps

- Creating A Complete Web App In Foundation For Apps

- Responsive Web Design: What It Is And How To Use It

- A Responsive Material Design App With Polymer Starter Kit

The Origin Of ConditionerJS

You know, obviously, that the way we access the Web has changed a lot in the last couple of years. We no longer rely solely on our desktop computers to navigate the Web. Rather, we use a wide and quickly growing array of devices to get our daily dose of information. With the device landscape going all fuzzy, the time of building fixed width desktop sites has definitely come to an end. The fixed canvas is breaking apart around us and needs to be replaced with something flexible — maybe even something organic.

What’s a Web Developer to Do?

Interestingly enough, most of the time, our content already is flexible. The styles, visuals and interaction patterns classically are rigid and are what create challenging to downright impossible situations. Turns out HTML (the contents container) has always been perfectly suited for a broad device landscape; the way we present it is what’s causing us headaches.

We should be striving to present our content, cross-device, in the best possible way. But let’s be honest, this “best possible way” is not three-width based static views, one for each familiar device group. That’s just a knee-jerk reaction, where we try to hang on to our old habits.

The device landscape is too broad and is changing too fast to be captured in groups. Right this moment people are making phone calls holding tablets to their heads while others are playing Grand Theft Auto on their phones until their fingers bleed. There’s phones that are tablets and tablets that are phones, there’s no way to determine where a phone ends a tablet starts and what device might fall in between, so let’s not even try.

Grouping devices is like grouping guinea pigs; while it’s certainly possible, eventually you will run into trouble.

To determine the perfect presentation and interaction patterns for each device, we need more granularity than device groups can give us. We can achieve a sufficient level of detail by looking at contextual information and measuring how it changes over time.

Context On The Web

The Free Dictionary defines “context” as follows:

“The circumstances in which an event occurs; a setting.”

The user’s context contains information about the environment in which that user is interacting with your functionality. Unlike feature detection, context is not static. You could be rotating your device right now, which would change the context in which you’re reading this article.

Measuring context is not only about testing hardware features and changes (such as viewport size and connection speed). Context can (and is) also influenced by the user’s actions. For instance, by now you’ve scrolled down this article a bit and might have moved your mouse a few pixels. This tells us something about the way you are interacting with the page. Collecting and combining all of this information will create a detailed picture of the context in which you’re currently reading this content.

Correctly measuring and responding to changes in context will enable us to present the right content in the right way at the right moment.

Note: If you’re interested in a more detailed analysis of context, I advise you to read Designing With Context by Cennydd Bowles.

Where And How To Measure Changes In Context

Measuring changes in context can easily be done by adding various tests to your JavaScript modules. You could, for example, listen to the resize and scroll events on the window or, a bit more advanced, watch for media query changes.

Let’s set up a small Google Maps module together. Because the map will feature urban areas and contain a lot of information, it should render only on viewports wider than 700 pixels. On smaller screens, we’ll show a link to Google Maps. We’ll write a bit of code to measure the window’s width to determine whether the window is wide enough to activate the map; if not, then no map. Perfect! What’s for dinner?

Don’t order that pizza just yet!

Your client has just called and would like to duplicate the map on another page. On this page, the map will show a less crowded area of the planet and so could still be rendered on viewports narrower than 700 pixels.

You could add another test to the map module, perhaps basing your measurement of width on some className? But what happens if a third condition is introduced, and a fourth. No pizza for you any time soon.

Clearly, measuring the available screen space is not this module’s main concern; the module should instead mostly be blowing the user’s mind with fantastic interaction patterns and dazzling maps.

This is where Conditioner comes into play. ConditionerJS will keep an eye on context-related parameters (such as window width) so that you can keep all of those measurements out of your modules. Specify the environment-related conditions for your module, and Conditioner will load your module once these conditions have been met. This separation of concerns will make your modules more flexible, reusable and maintainable — all favorable characteristics of code.

Setting Up A Conditioner Module

We’ll start with an HTML snippet to illustrate how a typical module would be loaded using Conditioner. Next, we’ll look at what’s happening under the hood.

<a href="http://maps.google.com/?ll=51.741,3.822"

data-module="ui/Map"

data-conditions="media:{(min-width:30em)} and element:{seen}"> … </a>

Codepen Example #1

We’re binding our map module using data attributes instead of classes, which makes it easier to spot where each module will be loaded. Also, binding functionality becomes a breeze. In the previous example, the map would load only if the media query (min-width:30em) is matched and the anchor tag has been seen by the user. Fantastic! How does this black magic work? Time to pop open the hood.

See the Pen ConditionerJS - Binding and Loading a Map Module by Rik Schennink (@rikschennink) on CodePen.

A Rundown of Conditioner’s Inner Workings

The following is a rundown of what happens when the DOM has finished loading. Don’t worry — it ain’t rocket surgery.

- Conditioner first queries the DOM for nodes that have the

data-moduleattribute. A simple querySelectorAll does the trick. - For each match, it tests whether the conditions set in the

data-conditionsattribute have been met. In the case of our map, it will test whether the media query has been matched and whether the element has scrolled into view (i.e. is seen by the user). Actually, this part could be considered rocket surgery. - If the conditions are met, then Conditioner will fetch the referenced module using RequireJS; that would be the

ui/Mapmodule. We use RequireJS because writing our own module loader would be madness — I’ve tried. - Once the module has loaded, Conditioner initializes the module at the given location in the DOM. Depending on the type of module, Conditioner will call the constructor or a predefined

loadmethod. - Presto! Your module takes it from there and starts up its map routine thingies.

After the initial page setup has been done, Conditioner does not stop measuring conditions. If they don’t match at first but are matched later on, perhaps the user decides to resize the window, Conditioner will still load the module. Also, if conditions suddenly become unsuitable the module will automatically be unloaded. This dynamic loading and unloading of modules will turn your static Web page into a living, growing, adaptable organism.

Available Tests And How To Use These In Expressions

Conditioner comes with basic set of tests that are all modules in themselves.

- “media”

queryandsupported - “element”

min-width,max-widthandseen - “window”

min-widthandmax-width - “pointer”

available

You could also write your own tests, doing all sorts of interesting stuff. For example, you could use this cookie consent test to load certain functionality only if the user has allowed you to write cookies. Also, what about unloading hefty modules if the battery falls below a certain level. Both possible. You could combine all of these tests in Conditioner’s expression language. You’ve seen this in the map tests, where we combined the seen test with the media test.

media:{(min-width:30em)} and element:{seen}

Combine parenthesis with the logical operators and, or and not to quickly create complex but still human-readable conditions.

Passing Configuration Options To Your Modules

To make your modules more flexible and suitable for different projects, allow for the configuration of specific parts of your modules — think of an API key for your Google Maps service, or stuff like button labels and URLs.

Configuring guinea pig facial expression using configuration objects.

Conditioner gives you two ways to pass configuration options to your modules: page- and node-level options. On initialization of your module, it will automatically merge these two option levels and pass the resulting configuration to your module.

Setting Default Module Options

Defining a base options property on your module and setting the default options object are a good start, as in the following example. This way, some sort of default configuration is always available.

// Map module (based on AMD module pattern)

define(function(){

// constructor

// element: the node that the module is attached to

// options: the merged options object

var exports = function Map(element,options) {

}

// default options

exports.options = {

zoom:5,

key:null

}

return exports;

});

By default, the map is set to zoom level 5 and has no API key. An API key is not something you’d want as a default setting because it’s kinda personal.

Defining Page-Wide Module Options

Page-level options are useful for overriding options for all modules on a page. This is useful for something like locale-related settings. You could define page-level options using the setOptions method that is available on the conditioner object, or you could pass them directly to the init method.

// Set default module options

conditioner.setOptions({

modules:{

'ui/Map':{

options:{

zoom:10,

key:'012345ABCDEF'

}

}

}

});

// Initialize Conditioner

conditioner.init();

In this case, we’ve set a default API key and increased the default zoom level to 10 for all maps on the page.

Overriding Options for a Particular Node

To alter options for one particular node on the page, use node-level options.

<a href="http://maps.google.com/?ll=51.741,3.822"

data-module="ui/Map"

data-options='{"zoom":15}'> … </a>

Codepen Example #2

For this single map, the zoom level will end up as 15. The API key will remain 012345ABCDEF because that’s what we set it to in the page-level options.

See the Pen ConditionerJS - Loading the Map Module and Passing Options by Rik Schennink (@rikschennink) on CodePen.

Note that the options are in JSON string format; therefore, the double quotes on the data-options attribute have been replaced by single quotes. Of course, you could also use double quotes and escape the double quotes in the JSON string.

Optimizing Your Build To Maximize Performance

As we discussed earlier, Conditioner relies on RequireJS to load modules. With your modules carefully divided into various JavaScript files, one file per module, Conditioner can now load each of your modules separately. This means that your modules will be sent over the line and parsed only once they’re required to be shown to the user.

To maximize performance (and minimize HTTP requests), merge core modules together into one package using the RequireJS Optimizer. The resulting minimized core package can then be dynamically enhanced with modules based on the state of the user’s active context.

Carefully balance what is contained in the core package and what’s loaded dynamically. Most of the time, you won’t want to include the more exotic modules or the very context-specific modules in your core package.

Try to keep your request count to a minimum — your users are known to be impatient.

Keep in mind that the more modules you activate on page load, the greater the impact on the CPU and the longer the page will take to appear. On the other hand, loading scripts conditionally will increase the CPU load needed to measure context and will add additional requests; also, this could affect page-redrawing cycles later on. There’s no silver bullet here; you’ll have to determine the best approach for each website.

The Future Of Conditioner

A lot more functionality is contained in the library than we’ve discussed so far. Going into detail would require more in-depth code samples, but because the API is still changing, the samples would not stay up to date for long. Therefore, the focus of this article has been on the concept of the framework and its basic implementation.

I’m looking for people to critically comment on the concept, to test Conditioner’s performance and, of course, to contribute, so that we can build something together that will take the Web further!

(al, ml, il)

(al, ml, il)