Testers are often thought of as people who find bugs, but have you ever considered how testers actually approach testing? Do you ever wonder what testers actually do, and how they can add value to a typical technology project?

I’d like to take you through the thought process of testers and discuss the types of things they consider when testing a mobile app. The intention here is to highlight their thought processes and to show the coverage and depth that testers often go to.

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Testing Mobile: Emulators, Simulators And Remote Debugging

- A Guide To Simple And Painless Mobile User Testing

- Applying Participatory Design To Mobile Testing

- Noah’s Transition To Mobile Usability Testing

Testers Ask Questions

At the heart of testing is the capability to ask challenging and relevant questions. You are on your way to becoming a good tester if you combine investigative and questioning skills with knowledge of technology and products.

For example, testers might ask:

- What platforms should this product work on?

- What is the app supposed to do?

- What happens if I do this?

And so forth.

Testers find questions in all sorts of places. It could be from conversations, designs, documentation, user feedback or the product itself. The options are huge… So, let’s dive in!

Where To Start Testing

In an ideal world, testers would all have up-to-date details on what is being built. In the real world, this is rare. So, like everyone else, testers make do with what they have. Don’t let this be an excuse not to test! Information used for testing can be gathered from many different sources, internally and externally.

At this stage questions, testers might ask these questions:

- What information exists? Specifications? Project conversations? User documentation? Knowledgeable team members? Could the support forum or an online company forum be of help? Is there a log of existing bugs?

- What OS, platform and device should this app work on and be tested on?

- What kind of data is processed by the application (i.e. personal, credit cards, etc.)?

- Does the application integrate with external applications (APIs, data sources)?

- Does the app work with certain mobile browsers?

- What do existing customers say about the product?

- How much time is available for testing?

- What priorities and risks are there?

- Who is experiencing pain, and why?

- How are releases or updates made?

Based on the information gathered, testers can put together a plan on how to approach the testing. Budgets often determine how testing is approached. You would certainly approach testing differently if you had one day instead of a week or a month. Predicting outcomes gets much easier as you come to understand the team, its processes and the answers to many of these types of questions.

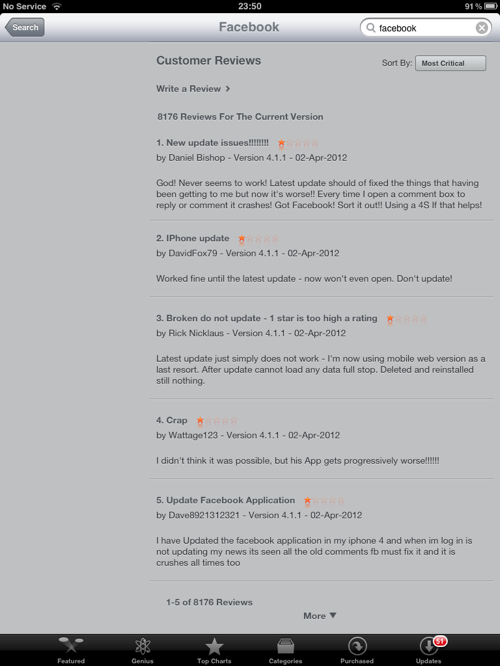

Example: Social Commentary on the Facebook App

I love using the Facebook app as an example when I’m gathering information as a tester. Complaints of it are everywhere. Just check out the comments in the iTunes App Store for some of the frustrations users are facing. Plenty more are dotted across the Web.

Facebook’s iPhone App has a lot of negative reviews.

If I were challenged to test the Facebook app, I would definitely take this feedback into consideration. I would be daft not to!

The Creativity Of Testers

You probably know what the app is meant to do, but what can it do? And how will people actually use it? Testers are great at thinking outside of the box, trying out different things, asking “What if” and “Why” constantly.

For example, mobile testers will often adopt the mindset of different types of people — not literally, of course, but the ability to think, analyze and visualize themselves as different users can be quite enlightening.

Testers might put themselves in these shoes:

- Novice user,

- Experienced user,

- Fan,

- Hacker,

- Competitor.

Many more personalities could be adopted; much of this really depends on what you are building. But it’s not just about personalities, but about behavior and workflows, too. People use products in strange ways. For example, they:

- Go back when they are not supposed to,

- Are impatient and hit keys multiple times,

- Enter incorrect data,

- Can’t figure out how to do something,

- Might not have the required setup,

- Might assume they know what they are doing (neglecting to read instructions, for example).

Testers look for these situations, often discovering unexpected results along the way. Sometimes the bugs initially found can appear small and insignificant, whereupon deeper investigation uncovers bigger problems.

Many of these issues can be identified up front with testing. When it comes to testing mobile apps, these might not all be relevant, but perhaps try asking questions such as these:

- Does it do what it says on the tin?

- Does the app perform the tasks it was designed to do?

- Does the app perform tasks that it wasn’t designed to do?

- How does the app perform when being used consistently or under a load? Is it sluggish? Does it crash? Does it update? Does it give feedback?

- Do crash reports give clues about the app?

- How can one navigate creatively, logically or negatively around the app?

- Does the user trust your brand?

- How secure is the user’s data?

- Is it possible to break or hack the app?

- What happens when you push the app to its limits?

- Does the app ask to turn on related services? (e.g. GPS, Wifi)? What if the user does? Or doesn’t?

- Where does the app redirect me? To the website? From website to app? Does it cause problems?

- Is communication and marketing consistent with the app’s function, design and content?

- What is the sign-up process like? Can it be done on the app? On a website?

- Does sign-up integrate with other services such as Facebook and Twitter?

Example: RunKeeper’s Buggy Update

RunKeeper, an app to track your fitness activities, recently released an update with new “Goal Setting” features. I was interested in giving it a try, a bit from a testing perspective, but also as a genuinely interested user. I discovered a few problems.

- It defaulted to pounds. I wanted weights in kilograms.

- Switching between pounds and kilograms just didn’t work properly.

- This ended up causing confusion and causing incorrect data and graphs to be shown when setting my goals.

- Because of that, I wanted to delete the goals, but found there was no way to do it in the mobile app.

- To work around this, I had to change my weight so that the app would register the goal as being completed.

- I could then try adding the goal again.

- Because of all of this confusion, I played around with it a bit more to see what other issues I could find.

Below are some screenshots of some of the issues found.

A recent update of RunKeeper included a new “Goals” section. Playing around with its dates, I discovered start and end dates could be set from the year 1 A.D. Also, why two years with “1”?

Another RunKeeper bug. This one is a typo in the “Current Weight” section. This happened when removing the data from the field. Typos are simple bugs to fix but look very unprofessional if ignored.

Here is the confusion that happened as a result of trying to switch between pounds and kilograms. If I want to lose 46 pounds, the bar actually shows 21 pounds.

There is no quick way to identify issues like these. Every app and team faces different challenges. However, one defining characteristic of testers is that they want to go beyond the limits, do the unusual, change things around, test over a long period of time — days, weeks or months instead of minutes — do what they have been told is not possible. These are the types of scenarios that often bring up bugs.

Where’s All The Data?

Testers like to have fun with data, sometimes to the frustration of developers. The reality is that confusing either the user or the software can be easy in the flow of information. This is ever more important with data- and cloud-based services; there is so much room for errors to occur.

Perhaps you could try checking out what happens in the following scenarios:

- The mobile device is full of data.

- The tester removes all of the data.

- The tester deletes the app. What happens to the data?

- The tester deletes then reinstalls the app.

- Too much or too little content causes the design or layout to change.

- Working with different times and time zones.

- Data does not sync.

- Syncing is interrupted.

- Data updates affect other services (such as websites and cloud services).

- Data is processed rapidly or in large amounts.

- Invalid data is used.

Example: Soup.me Is Wrong

I was trying out Soup.me, a Web service that sorts your Instagram photos by map and color, but I didn’t get very far. When I tried to sign up, it said that I didn’t have enough Instagram photos. This is a lie not true because I have published over 500 photos on my Instagram account. It’s not clear what the problem was here. It could have been a data issue. It could have been a performance issue. Or perhaps it was a mistake in the app’s error messages.

Another Example: Quicklytics

Quickytics is a Web analytics iPad app. In my scenario, a website profile of mine still exists despite my having deleted it from my Google Analytics account. My questions here are:

- I have deleted this Web profile, so why is this still being displayed?

- The left panel doesn’t appear to have been designed to account for no data. Could this be improved to avoid confusing the user?

Testers like to test the limits of data, too. They will often get to know the app as a typical user would, but pushing the limits doesn’t take them long. Data is messy, and testers try to consider the types of users of the software and how to test in many different scenarios.

For example, they might try to do the following:

- Test the limits of user input,

- Play around with duplicate data,

- Test on brand new clean phone,

- Test on an old phone,

- Pre-populate the app with different types of data,

- Consider crowd-sourcing the testing,

- Automate some tests,

- Stress the app with some unexpected data to see how it copes,

- Analyze how information and data affects the user experience,

- Always question whether what they see is correct,

Creating Errors And Messages

I’m not here to talk about (good) error message design. Rather, I’m approaching this from a user and tester’s point of view. Errors and messages are such common places for testers to find problems.

Questions to Ask About Error Messages

Consider the following questions:

- Is the UI for errors acceptable?

- Are error messages accessible?

- Are error messages consistent?

- Are they helpful?

- Is the content appropriate?

- Do errors adhere to good practices and standards?

- Are the error messages security-conscious?

- Are logs and crashes accessible to user and developer?

- Have all errors been produced in testing?

- What state is the user left in after an error message?

- Have no errors appeared when they should have?

Error messages quite often creep into the user experience. Bad and unhelpful errors are everywhere. Trying to stop users from encountering error messages would be ideal, but this is probably impossible. Errors can be designed for and implemented and verified against expectations, but testers are great at finding unexpected bugs and at carefully considering whether what they see could be improved.

Some Examples of Error Messages

I like the example below of an error message in the Facebook app on the iPhone. Not only is the text somewhat longwinded and sheepishly trying to cover many different scenarios, but there is also the possibility that the message gets lost into the ether.

Perhaps the messages below are candidates for the Hall of Fame of how not to write messages?

What about this one from The Guardian’s app for the iPad? What if I don’t want to “Retry”?

Platform-Specific Considerations

Becoming knowledgeable about the business, technology and design constraints of relevant platforms is crucial for any project team member.

So, what types of bugs do testers look for in mobile apps?

- Does it follow the design guidelines for that particular platform?

- How does the design compare with designs by competitors and in the industry?

- Does the product work with peripherals?

- Does the touchscreen support gestures (tap, double-tap, touch and hold, drag, shake, pinch, flick, swipe)?

- Is the app accessible?

- What happens when you change the orientation of the device?

- Does it make use of mapping and GPS?

- Is there a user guide?

- Is the email workflow user-friendly?

- Does the app work smoothly when sharing through social networks? Does it integrate with other social apps or websites?

- Does the app behave properly when the user is multitasking and switching between apps?

- Does the app update with a time stamp when the user pulls to refresh?

- What are the app’s default settings? Have they been adjusted?

- Does audio make a difference?

Example: ChimpStats

ChimpStats is an iPad app for viewing details of email campaigns. I first started using the app in horizontal mode. I got a bit stuck as soon as I wanted to enter the API key. I couldn’t actually enter any content into the API field unless I rotated it vertically.

Connectivity Issues And Interruption

Funny things can happen when connections go up and down or you get interrupted unexpectedly.

Have you tried using the app in the following situations:

- Moving about?

- With Wi-Fi connectivity?

- Without Wi-Fi?

- On 3G?

- With intermittent connectivity?

- Set to airplane mode?

- When a phone call comes in?

- While receiving a text message?

- When receiving an app notification?

- With low or no battery life?

- When the app forces an update?

- When receiving a voicemail?

These types of tests are a breeding ground for errors and bugs. I highly recommend testing your app in these conditions — not just starting it up and checking to see that it works, but going through some user workflows and forcing connectivity and interruptions at particular intervals.

- Does the app provide adequate feedback?

- Does data get transmitted knowingly?

- Does it grind to a halt and then crash?

- What happens when the app is open?

- What happens midway through a task?

- Is it possible to lose your work?

- Can you ignore a notification? What happens?

- Can you respond to a notification? What happens?

- Is any (error) messaging appropriate when something goes wrong?

- What happens if your log-in expires or times out?

Maintaining The App

Speeding up the process of testing an app is so easy. Test it once and it will be OK forever, right?

Think again.

One problem I’m facing at the moment with some apps on my iPad is that they won’t download after being updated. As a user, this is very frustrating.

Perhaps this is out of the control of the app’s developer. Who knows? All I know is that it doesn’t work for me as a user. I’ve tried removing the app and then reinstalling, but the problem still occurs. I’ve done a bit of searching; no luck with any of my questions, aside from suggestions to update my OS. Perhaps I’ll try that next… when I have time.

The point is, if the app was tested once and only once (or over a short period of time), many problems could have gone undetected. Your app might not have changed, but things all around it could make it break.

When things are changing constantly and quickly, how does it affect your app? Ask yourself:

- Can I download the app?

- Can I download and install an update?

- Does the app still work after updating?

- Can I update the app when multiple updates are waiting?

- What happens if the OS is updated?

- What happens if the OS is not updated?

- Does the app automatically sync downloading to other devices via iTunes?

- Is it worth automating some tasks or tests?

- Does the app communicate with Web services? How would this make a difference?

Testing your mobile app after each release would be wise. Define a set of priority tests to cover at each new release, and make sure the tests are performed in a variety of conditions — perhaps on the most popular platforms. Over time, it might be worth automating some tests — but remember that automated tests are not a magic bullet; some problems are spotted only by a human eye.

Example: Analytics App on the iPhone

I’ve had this app for two years now. It’s worked absolutely fine until recently; now, it has been showing no data for some of my websites (yes, more than one person has visited my website over the course of a month!). A quick look at the comments in the app store showed that I wasn’t the only one with this problem.

Here is another example from the Twitter app for the iPhone. After updating and starting up the app, I saw this message momentarily (Note: I have been an active tweeter for five years). I got a bit worried for a second! Thankfully, the message about having an empty timeline disappeared quickly and of its own accord.

Testing Is Not Clear-Cut

We’ve covered some ground of what mobile testing can cover, the basis of it being: with questions, we can find problems.

All too often, testing is thought of as being entirely logical, planned and predictable, full of processes, test scripts and test plans, passes and fails, green and red lights. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

Sure, we can have these processes if and when necessary, but this shouldn’t be the result of what we do. We’re not here just to create test cases and find bugs. We’re here to find the problems that matter, to provide information of value that enables other project members to confidently decide when to release. And the best way we get there is by asking questions!

(al)

(al)