Ah, the ubiquitous CSS sprites — one of the few web design techniques that was able to bypass “trend” status almost instantly, planting itself firmly into the category of best practice CSS. Although it didn’t really take off until well after A List Apart explained and endorsed it, it was discussed as a CSS solution as early as July, 2003 by Petr Stanícek.

Most web developers today have a fairly strong grasp of this technique, and there have been countless tutorials and articles written on it. In almost every one of those tutorials, the claim is made that designers and developers should be implementing CSS sprites in order to minimize HTTP requests and save valuable kilobytes. This technique has been taken so far that many sites, including Amazon, now use mega sprites.

You may also want to take a look at the following related posts:

- CSS Sprites Revisited

- Transparent CSS Sprites

- The Mystery Of CSS Sprites: Techniques, Tools And Tutorials

- Coding Q&A With Chris Coyier: Box-Sizing and CSS Sprites

Is this much-discussed benefit really worthwhile? Are designers jumping on the CSS sprite bandwagon without a careful consideration of all the factors? In this article, I’m going to discuss some of the pros and cons of using CSS sprites, focusing particularly on the use of “mega” sprites, and why such use of sprites could in many cases be a waste of time.

Browsers Cache All Images

One of the benefits given by proponents of the sprite method is the load time of the images (or in the case of mega sprites, the single image). It’s argued that a single GIF image comprising all the necessary image states will be significantly lower in file size than the equivalent images all sliced up. This is true. A single GIF image has only one color table associated with it, whereas each image in the sliced GIF method will have its own color table, adding up the kilobytes. Likewise, a single JPEG or PNG sprite will likely save on file size over the same image sliced-up into multiple images. But is this really such a significant benefit?

By default, image-based browsers will cache all images — whether the images are sprites or not. So, while it is certainly true that bandwidth will be saved with the sprite technique, this only occurs on the initial page load, and the caching will extend to secondary pages that use the same image URLs.

The Firefox cache displaying images from amazon.com that the browser cached (type “about:cache” in the address bar in Firefox to view this feature).

When you combine that with the fact that internet speeds are higher on average today than they were when this technique was first expounded upon in 2003-2004, then there may be little reason to use the mega sprite method. And just to be clear, as already mentioned, I’m not saying sprites should never be used; I’m saying they should not be overused to attain limited benefits.

Time Spent Slicing a Design Will Increase

Think about how a simple 3-state image button sprite is created: The different states need to be placed next to one another, forming a single image. In your Photoshop mockup (or other software), you don’t have the different states adjacent to each other in that manner; they need to be sliced and combined into a new separate image, outside of the basic website mockup.

If any changes are required for any one of the image states, the entire image needs to be recompiled and resaved. Some developers may not have a problem with this. Maybe they keep their button states separate from the mockup in a raw original, making it easier to access them. But this complicates things, and will never be as simple as slicing a single image and exporting it.

For the minimal benefit of a few kilobytes and server requests saved (which only occurs on initial page load), is the mega sprite method really a practical solution for anything other than a 3-state button?

Time Spent Coding and Maintaining Will Increase

After an image is sliced and exported, the trouble doesn’t end there. While button sprites are simple to code into your CSS once you’re accustomed to the process, other kinds of sprites are not so simple.

A single button will usually be a <ul> element that has a set width. If the sprites for the button are separate for each button, it’s simple: The width and height of the <ul> will be the same as the width and height of the list item and anchor, with the sprite aligned accordingly for each state. The position of the sprite is easily calculated based on the height and/or width of each button.

But what about a mega sprite, like the one used by Amazon, mentioned earlier, or the one used by Google? Can you imagine maintaining such a file, and making changes to the position of the items in the CSS? And what about the initial creation of the CSS code? Far from being a simple button whose state positions are easily calculated, the mega sprite will often require continuous testing and realigning of the image states.

![]()

Some of the CSS used to position Google’s sprite image

It’s true that the Amazon sprite saves about 30 or more HTTP requests, and that is definitely a significant improvement in performance. But when that benefit is weighed against the development and maintenance costs, and the caching and internet speed issues are factored in, the decision to go with sprites in the mega format may not be so convincing.

Do Sprites Really Require “Maintenance”?

Of course, some may feel that sprites do not cause a major headache for them. In many cases, after a sprite is created and coded, it’s rarely touched again, and isn’t affected by any ongoing website maintenance. If you feel that sprite maintenance won’t be an issue for you, then the best choice may be to use the mega sprite method.

Not Everything Should Be a Background

Another reason not to promote the overuse of CSS sprites is that it could cause developers to use background images incorrectly. Experienced developers who consider accessibility in their projects understand that not every image should be a background. Images that convey important content should be implemented through inline images in the XHTML, whereas background images should be reserved for buttons and decorative elements.

Amazon correctly places content images as inline elements, and decorative ones as backgrounds.

Improper Use of Sprites Affects Accessibility

Because of the strong emphasis placed on using CSS sprites, some beginning developers intending on saving HTTP requests may incorrectly assume that all sliced images should be placed as backgrounds — even images that convey important information. The results would be a less accessible site, and would limit the potential benefits of the title and alt attributes in the HTML.

So, while CSS sprites in and of themselves are not wrong, and do not cause accessibility problems (in fact, when used correctly, they improve accessibility), the over-promotion of sprites without clearly identifying drawbacks and correct use could hinder the progress the web has made in areas of accessibility and productivity.

What About HTTP Requests?

Many will argue, however (and for good reason) that the most important part of improving a site’s performance is minimizing HTTP requests. It should also be noted that one study conducted showed that 40-60% of daily website visitors come with an empty browser cache. Is this enough to suggest that mega sprites should be used in all circumstances? Possibly. Especially when you consider how important a user’s first visit to a website is.

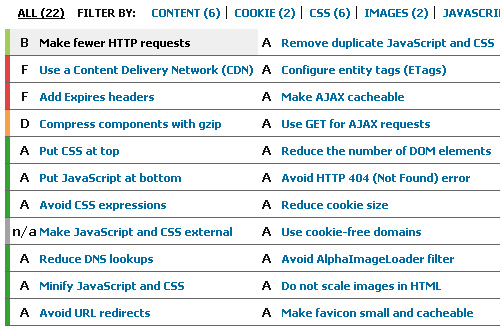

The YSlow Firefox add-on that analyzes performance shows the number of HTTP requests being made

While it is true that older browsers generally only allowed two simultaneous HTTP connections, Firefox since version 3.0 and Internet Explorer 8 by default allow 6 simultaneous HTTP connections. This means 6 simultaneous connections per server. To quote Steve Souders:

It’s important to understand that this is on a per server basis. Using multiple domain names, such as 1.mydomain.com, 2.mydomain.com, 3.mydomain.com, etc., allows a web developer to achieve a multiple of the per server connection limit. This works even if all the domain names are CNAMEs to the same IP address.

So, while there could be a benefit to using CSS sprites beyond just button states, in the future, as internet connection speeds increase and newer browser versions make performance improvements, the benefits that come from using mega sprites could become almost irrelevant.

What About Sprite Generators?

Another argument in favour of mega sprites is the apparent ease with which sprites can be created using a number of sprite generators. A detailed discussion and review of such tools is well beyond the scope of this article, so I’ll avoid that here. But from my research of these tools, the help they provide is limited, and maintenance of the sprites will still take a considerable amount of work, which again should be weighed against the benefits.

Some tools, like the one by Project Fondue, offer CSS output options. Steve Souders’ tool SpriteMe is another one that offers CSS coding options. SpriteMe will convert an existing website’s background images into a single sprite image (what I’ve been referring to as a “mega” sprite) that you can download and insert into your page with the necessary CSS code. While this tool will assist with the creation of sprites, it doesn’t seem to offer much help in the area of sprite maintenance. Souders’ tool seems to be useless for a website that is redesigned or realigned, and only seems to provide benefit to an existing design that has not yet used the mega sprite method.

Improvements to current tools could be made, and newer tools could appear in the future. But is it possible, due to some of the drawbacks mentioned above, that developers are focusing a lot of effort on a very minimal gain?

Focus Should be on Multiple Performance Issues

As mentioned, the number of HTTP requests is an important factor to consider in website performance. But there are other ways to lower that number, including combining scripts and stylesheets, and using remote locations for library files.

There are also areas outside of HTTP requests that a developer can focus on to improve site performance. These might include GZipping, proper placement of external scripts, optimizing CSS syntax, minifying large JavaScript files, improving Ajax performance, avoiding JavaScript syntax that’s known to cause performance issues, and much more.

YSlow indicates many areas outside of HTTP requests that can improve site performance

If developers take the time to consider all factors in website performance, and weigh the pros and cons correctly, there may be good reason to avoid overusing CSS sprites, and focusing on areas whose performance return is worth the investment.

Conclusion

Please don’t misinterpret anything that I’ve said here. Many top bloggers and developers have for years extolled the benefits of using sprites, and in recent years taken those suggestions further in promoting the use of mega sprites — so those opinions should be taken seriously. However, not everyone has the luxury of working in a company that has policies and systems in place that make website maintenance tasks simple and streamlined. Many of us work on our own, or have to inherit projects created by others. In those cases, mega sprites may cause more trouble than they’re worth.

What do you think? Should we reconsider the use of mega sprites in CSS development? Do the statistics in favour of the savings on HTTP requests warrant the use of sprites for all background images? Or have sprites in CSS development evolved from a useful, intuitive and productive technique to a time-consuming nuisance?